Kevin Berger in Nautilus:

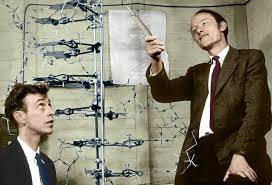

James Watson once said his road to the 1962 Nobel Prize began in Naples, Italy. At a conference in 1951, he met Maurice Wilkins, the biophysicist with whom he and Francis Crick shared the Nobel for discovering the double-helix structure of DNA. Meeting Wilkins was when he “first realized that DNA might be soluble,” Watson said. “So my life was changed.” That’s a nice anecdote for the science textbooks. But there’s “a tawdry first act to this operetta,” writes Howard Markel in his new book, The Secret of Life, about the drama behind the scenes of the famous discovery. At the time, Watson was an arrogant, gawky 22-year-old, working as a postdoctoral fellow at the University of Copenhagen. His biology lab director, Herman Kalckar, invited Watson and another fellow in the lab, Barbara Wright, to accompany him to the Naples conference. The confident and competitive Watson didn’t think much of Wright’s work. It was “rather inexact,” he sniped. But Watson was pleased to be invited on the trip. “It should be quite exciting,” he wrote his parents.

James Watson once said his road to the 1962 Nobel Prize began in Naples, Italy. At a conference in 1951, he met Maurice Wilkins, the biophysicist with whom he and Francis Crick shared the Nobel for discovering the double-helix structure of DNA. Meeting Wilkins was when he “first realized that DNA might be soluble,” Watson said. “So my life was changed.” That’s a nice anecdote for the science textbooks. But there’s “a tawdry first act to this operetta,” writes Howard Markel in his new book, The Secret of Life, about the drama behind the scenes of the famous discovery. At the time, Watson was an arrogant, gawky 22-year-old, working as a postdoctoral fellow at the University of Copenhagen. His biology lab director, Herman Kalckar, invited Watson and another fellow in the lab, Barbara Wright, to accompany him to the Naples conference. The confident and competitive Watson didn’t think much of Wright’s work. It was “rather inexact,” he sniped. But Watson was pleased to be invited on the trip. “It should be quite exciting,” he wrote his parents.

Watson was bored with most of the presentations at the conference. But he perked up when Wilkins projected images of DNA, captured with X-ray crystallography. The novel image showed the molecule arose from a crystalline structure. Watson later tried to buddy up to Wilkins at a cocktail party, but the socially awkward Wilkins did his best to avoid the bumptious American. Watson thought he had another opening when he spotted Wilkins chatting with his sister, who had joined Watson in Naples. But when Watson approached them, Wilkins slipped away.

Nonetheless, Watson’s encounter with Wilkins cemented his future. He was determined to discover the precise molecular structure of DNA. He knew he had little chance to join Wilkins at his lab at King’s College at the University of London, mainly because Wilkins didn’t like him. Watson set his sights on joining the other prominent biology lab probing molecular structures. At Cavendish Laboratory Biophysics Unit at Cambridge, Watson met the intellectually unstoppable Crick, and in two years, the duo built the first sound model of DNA’s structure. Their model showed the world how DNA did its thing and shaped the course of biological life.

In The Secret of Life, Markel, a distinguished professor in the history of medicine at the University of Michigan, and author of nonfiction books that roll along like novels, relishes explaining the backstory to Watson’s and Wilkins’ first encounter. Turns out Kalckar was having an affair with Wright and wanted to keep their trysts secret. Watson was invited to Naples “to act as a beard for his boss, to provide cover for his affair with Wright,” Markel told me in a recent interview. In The Secret of Life, Markel writes, “one cannot help but smile at the paradox that the unraveling of the double helix of DNA began with the coupling of Kalckar and Wright.”

More here.

Rachel Kushner in n+1:

Rachel Kushner in n+1: Megan Marz in The Baffler:

Megan Marz in The Baffler: A forum over at The Boston Review with a lead piece by Dan Breznitz:

A forum over at The Boston Review with a lead piece by Dan Breznitz: For many people, the Golden Record was less a testament to belief in alien life than a gesture: humanity’s bold shout into the abyss. Indeed, facing criticism about the project, those behind it sometimes insisted it should be taken symbolically. Yet the care that went into the design of the records belies this dismissal. In a 2017 essay for the New Yorker, Timothy Ferris, one of the architects of the Golden Record, explained that the overrepresentation of Bach and Beethoven was meant to aid aliens in understanding the music, even if their hearing doesn’t resemble ours. “They’d look for symmetries—repetitions, inversions, mirror images, and other self-similarities—within or between compositions,” he hypothesized. “We sought to facilitate the process by proffering Bach, whose works are full of symmetry, and Beethoven, who championed Bach’s music and borrowed from it.” The careful curation—not to mention the bare bones of a turntable included with the records, along with a detailed diagram for its assembly—suggests that the Golden Record was not a lark, but a serious attempt to reach someone.

For many people, the Golden Record was less a testament to belief in alien life than a gesture: humanity’s bold shout into the abyss. Indeed, facing criticism about the project, those behind it sometimes insisted it should be taken symbolically. Yet the care that went into the design of the records belies this dismissal. In a 2017 essay for the New Yorker, Timothy Ferris, one of the architects of the Golden Record, explained that the overrepresentation of Bach and Beethoven was meant to aid aliens in understanding the music, even if their hearing doesn’t resemble ours. “They’d look for symmetries—repetitions, inversions, mirror images, and other self-similarities—within or between compositions,” he hypothesized. “We sought to facilitate the process by proffering Bach, whose works are full of symmetry, and Beethoven, who championed Bach’s music and borrowed from it.” The careful curation—not to mention the bare bones of a turntable included with the records, along with a detailed diagram for its assembly—suggests that the Golden Record was not a lark, but a serious attempt to reach someone. Of course, few modern scholars accept either Hobbes’s bleak caricature or Rousseau’s romantic musings. Nonetheless, Graeber and Wengrow argue, these antithetical conceptions of human nature feed into the consensus that has been popularised by figures such as Diamond and Harari.

Of course, few modern scholars accept either Hobbes’s bleak caricature or Rousseau’s romantic musings. Nonetheless, Graeber and Wengrow argue, these antithetical conceptions of human nature feed into the consensus that has been popularised by figures such as Diamond and Harari. As a novel, “Dune” has never been unconditionally admired. I know sophisticated readers, devoted science fiction fans, who can’t stand it, finding Herbert’s prose inept, the action ponderous, and the whole book clumsy and tedious. But sf readers are contentious, often cruelly so, and nearly all of the field’s most beloved novels and series also have cogent and vocal detractors: Isaac Asimov’s “

As a novel, “Dune” has never been unconditionally admired. I know sophisticated readers, devoted science fiction fans, who can’t stand it, finding Herbert’s prose inept, the action ponderous, and the whole book clumsy and tedious. But sf readers are contentious, often cruelly so, and nearly all of the field’s most beloved novels and series also have cogent and vocal detractors: Isaac Asimov’s “ In May 1453, Ottoman military forces under Sultan Mehmed II captured the once great Byzantine capital of Constantinople, now Istanbul. It was a landmark moment. What was viewed as one of the greatest cities of Christendom, and described by the sultan as “the second Rome”, had fallen to Muslim conquerors. The sultan even called himself “caesar”.

In May 1453, Ottoman military forces under Sultan Mehmed II captured the once great Byzantine capital of Constantinople, now Istanbul. It was a landmark moment. What was viewed as one of the greatest cities of Christendom, and described by the sultan as “the second Rome”, had fallen to Muslim conquerors. The sultan even called himself “caesar”. We turn to the Internet for answers. We want to connect, or understand, or simply appreciate something—even if it’s only Joe Rogan. It’s a fraught pursuit. As the Web keeps expanding faster and faster, it’s become saturated with lies and errors and loathsome ideas. It’s a Pacific Ocean that washes up skeevy wonders from its Great Garbage Patch. We long for a respite, a cove where simple rules are inscribed in the sand.

We turn to the Internet for answers. We want to connect, or understand, or simply appreciate something—even if it’s only Joe Rogan. It’s a fraught pursuit. As the Web keeps expanding faster and faster, it’s become saturated with lies and errors and loathsome ideas. It’s a Pacific Ocean that washes up skeevy wonders from its Great Garbage Patch. We long for a respite, a cove where simple rules are inscribed in the sand. In the last chapter of his first book, Reign of Terror: How the 9/11 Era Destabilized America and Produced Trump, Spencer Ackerman reminds his readers of Bernie Sanders’s June 2019 assertion: “There is a straight line from the decision to reorient U.S. national-security strategy around terrorism after 9/11 to placing migrant children in cages on our southern border.”

In the last chapter of his first book, Reign of Terror: How the 9/11 Era Destabilized America and Produced Trump, Spencer Ackerman reminds his readers of Bernie Sanders’s June 2019 assertion: “There is a straight line from the decision to reorient U.S. national-security strategy around terrorism after 9/11 to placing migrant children in cages on our southern border.” Academics use the category of magic, well, often magically, to dismiss the phenomenon they are studying, to banish the subject matter from living contact with their present reality. Ancient philosophy is over there, good and dead, and we enlightened modern philosophers and scholars are over here, living, present, pristine and modern, washed clean of ancient superstitions. But magic is rather sticky, hard to wash off from the hands or the delicate underside of the modern mind, to which it clings like a sinister visitor who has always arrived, but is still waiting to announce itself.

Academics use the category of magic, well, often magically, to dismiss the phenomenon they are studying, to banish the subject matter from living contact with their present reality. Ancient philosophy is over there, good and dead, and we enlightened modern philosophers and scholars are over here, living, present, pristine and modern, washed clean of ancient superstitions. But magic is rather sticky, hard to wash off from the hands or the delicate underside of the modern mind, to which it clings like a sinister visitor who has always arrived, but is still waiting to announce itself. Take the word “understand;” in daily communication we rarely parse it’s implications, but the word itself is a spatial metaphor. Linguist Guy Deutscher explains in

Take the word “understand;” in daily communication we rarely parse it’s implications, but the word itself is a spatial metaphor. Linguist Guy Deutscher explains in  For the longest part of our history, humans lived as hunter-gatherers who neither experienced economic growth nor worried about its absence. Instead of working many hours each day in order to acquire as much as possible, our nature—insofar as we have one—has been to do the minimum amount of work necessary to underwrite a good life.

For the longest part of our history, humans lived as hunter-gatherers who neither experienced economic growth nor worried about its absence. Instead of working many hours each day in order to acquire as much as possible, our nature—insofar as we have one—has been to do the minimum amount of work necessary to underwrite a good life. Sometimes our most precious cultural institutions fail to live up to their high educational and moral commitments and responsibilities. These failures especially damage the social fabric because they tend to harm many people who rely on them and tarnish the high ideals that the institutions claim to exemplify.

Sometimes our most precious cultural institutions fail to live up to their high educational and moral commitments and responsibilities. These failures especially damage the social fabric because they tend to harm many people who rely on them and tarnish the high ideals that the institutions claim to exemplify.