Kylie Cheung in Salon:

Nearly three years ago, Christine Blasey Ford testified before the U.S. Senate that then-Supreme Court Justice nominee Brett Kavanaugh had sexually assaulted her decades ago. In many ways, her testimony, which became a watershed moment for survivors and women in politics, was able to happen because of the Black woman who had come before her: Anita Hill. A new podcast called “Because of Anita” revisits how in 1991, Hill testified that then-Supreme Court Justice nominee Clarence Thomas had sexually harassed her while she worked for him. Not only did her testimony introduce the concept of workplace sexual harassment into the lexicon, but it had galvanized generations of women, and shined a light on the unique experiences of Black women who seek safety and justice.

Nearly three years ago, Christine Blasey Ford testified before the U.S. Senate that then-Supreme Court Justice nominee Brett Kavanaugh had sexually assaulted her decades ago. In many ways, her testimony, which became a watershed moment for survivors and women in politics, was able to happen because of the Black woman who had come before her: Anita Hill. A new podcast called “Because of Anita” revisits how in 1991, Hill testified that then-Supreme Court Justice nominee Clarence Thomas had sexually harassed her while she worked for him. Not only did her testimony introduce the concept of workplace sexual harassment into the lexicon, but it had galvanized generations of women, and shined a light on the unique experiences of Black women who seek safety and justice.

“There was an understanding [in 1991] — white women stood for gender, and Black men stood for race,” Cindi Leive, who co-hosts of the podcast along with New York Times cultural critic Dr. Salamishah Tillet, told Salon. “As a Black woman, she was in no woman’s land. . . . And it was really important for us to foreground that in this podcast.” At the time, it was precisely this limited conception of identity and its intersections that labeled Hill as a “race traitor,” a Black woman playing the part of a white woman for challenging Thomas, who was seen as representing all Black people as a Black man.

That’s why 30 years later, Anita Hill’s story feels more relevant than ever. To examine its impact and gain new insights, the four-part podcast features a conversation between Hill and Dr. Ford, as well as numerous interviews. Legal scholar Kimberlé Crenshaw in particular recalls attending the hearing and discusses intersectionality, a term she coined, in relation to Hill’s story and our understanding of it today. Other guests include: journalist Jane Mayer; Kerry Washington, who portrays Hill in “Confirmation”; Carol Moseley Braun, the first Black woman U.S. Senator; Me Too founder Tarana Burke; and a wide range of other expert voices.

More here.

I

I  Renewable energy seems set to repeat many of the mistakes of fossil fuels. Though wind and solar power will not degrade the conditions for life on planet earth, the geography and corporate structure of these industries concentrate benefits and exclude communities in the style of Big Oil. The neighbors tend to notice—and to complain. So-called “

Renewable energy seems set to repeat many of the mistakes of fossil fuels. Though wind and solar power will not degrade the conditions for life on planet earth, the geography and corporate structure of these industries concentrate benefits and exclude communities in the style of Big Oil. The neighbors tend to notice—and to complain. So-called “ Those of us who think that that

Those of us who think that that  Curiosity is very closely related to one of my most highly prized traits, what Keats called “negative capability”… “when a man is capable of being in uncertainties, mysteries, doubts, without any irritable reaching after fact and reason.” There’s whiff of Romantic mysticism about this, for sure, but I see it primarily as openness to complexity, comfort with ambiguity, patience with not knowing. (If you’ve never read it, “

Curiosity is very closely related to one of my most highly prized traits, what Keats called “negative capability”… “when a man is capable of being in uncertainties, mysteries, doubts, without any irritable reaching after fact and reason.” There’s whiff of Romantic mysticism about this, for sure, but I see it primarily as openness to complexity, comfort with ambiguity, patience with not knowing. (If you’ve never read it, “

Cynthia Ozick’s surprisingly scalding and chaotic

Cynthia Ozick’s surprisingly scalding and chaotic  For many of us over the last year and more, our waking experience has, you might say, lost a bit of its variety. We spend more time with the same people, in our homes, and go to fewer places. Our stimuli these days, in other words, aren’t very stimulating. Too much day-to-day routine, too much familiarity, too much predictability. At the same time, our dreams have gotten more

For many of us over the last year and more, our waking experience has, you might say, lost a bit of its variety. We spend more time with the same people, in our homes, and go to fewer places. Our stimuli these days, in other words, aren’t very stimulating. Too much day-to-day routine, too much familiarity, too much predictability. At the same time, our dreams have gotten more  The works carry a metaphysical meaning, as well as a geographical one. With the skulls and antlers, bones and shells, O’Keeffe creates a secular iconography. For her, these subjects did not represent death but something vital and lasting. A bone found in the desert is like a shell found on the beach: both are forms defined by function, both are beautiful and enduring evidence of life. O’Keeffe’s images and juxtapositions are mysterious, but she wasn’t a member of the Surrealist movement, which deliberately juxtaposed objects without connections to one another. Her intention was quite different: these objects have a deep connection—one that we recognize on an intuitive level. “Pelvis with the Distance,” from 1943, shows a smooth, white bone, all curves and slopes and openings. It is suspended, high in the air, above a line of low, undulant blue hills. This physical juxtaposition—the celestial locus of the bone, the earth-hugging horizon below—creates a majestic sweep of space. O’Keeffe places the viewer aloft, level with the bone, high up in the empyrean. The supernatural height, the mystery, the hallucinatory beauty of the object—all combine to create a sense of the sublime.

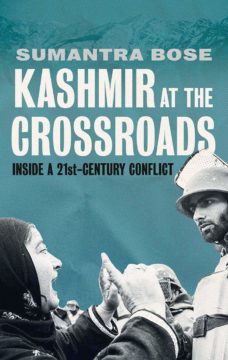

The works carry a metaphysical meaning, as well as a geographical one. With the skulls and antlers, bones and shells, O’Keeffe creates a secular iconography. For her, these subjects did not represent death but something vital and lasting. A bone found in the desert is like a shell found on the beach: both are forms defined by function, both are beautiful and enduring evidence of life. O’Keeffe’s images and juxtapositions are mysterious, but she wasn’t a member of the Surrealist movement, which deliberately juxtaposed objects without connections to one another. Her intention was quite different: these objects have a deep connection—one that we recognize on an intuitive level. “Pelvis with the Distance,” from 1943, shows a smooth, white bone, all curves and slopes and openings. It is suspended, high in the air, above a line of low, undulant blue hills. This physical juxtaposition—the celestial locus of the bone, the earth-hugging horizon below—creates a majestic sweep of space. O’Keeffe places the viewer aloft, level with the bone, high up in the empyrean. The supernatural height, the mystery, the hallucinatory beauty of the object—all combine to create a sense of the sublime. With admirable clarity, Sumantra Bose’s Kashmir at the Crossroads helps to explain the tensions and the motives of the various parties involved in the intractable Kashmir conflict, including Chinese cartographers, Indian Hindu nationalists, Pakistani intelligence officers, violent jihadists and the group that barely gets a look in, the Kashmiris themselves. Landlocked and surrounded by three antagonistic nuclear powers with claims on their land, the Kashmiris are always the last ones to have a say over their own future.

With admirable clarity, Sumantra Bose’s Kashmir at the Crossroads helps to explain the tensions and the motives of the various parties involved in the intractable Kashmir conflict, including Chinese cartographers, Indian Hindu nationalists, Pakistani intelligence officers, violent jihadists and the group that barely gets a look in, the Kashmiris themselves. Landlocked and surrounded by three antagonistic nuclear powers with claims on their land, the Kashmiris are always the last ones to have a say over their own future. A young musician attends the conservatory, a young artist studies at the academy, but the young writer has nowhere to go. You view this as an injustice. Not so. Schools for musicians and painters provide first and foremost technical knowledge you’d be hard pressed to acquire on your own in relatively short order. What is the writer to learn at his institute? Any ordinary school is all it takes to push a pen across the page. Literature holds no technical secrets, or at least secrets that can’t be plumbed by a gifted amateur (since no diploma will help the talentless). It’s the least professional of all artistic callings. You may take up writing at twenty or seventy. You may be a professor or an autodidact. You may skip your high school diploma (like Thomas Mann) or receive honorary doctorates at multiple universities (again like Mann). The road to Parnassus is open to all. In principle at least, since genes have the final say.

A young musician attends the conservatory, a young artist studies at the academy, but the young writer has nowhere to go. You view this as an injustice. Not so. Schools for musicians and painters provide first and foremost technical knowledge you’d be hard pressed to acquire on your own in relatively short order. What is the writer to learn at his institute? Any ordinary school is all it takes to push a pen across the page. Literature holds no technical secrets, or at least secrets that can’t be plumbed by a gifted amateur (since no diploma will help the talentless). It’s the least professional of all artistic callings. You may take up writing at twenty or seventy. You may be a professor or an autodidact. You may skip your high school diploma (like Thomas Mann) or receive honorary doctorates at multiple universities (again like Mann). The road to Parnassus is open to all. In principle at least, since genes have the final say.

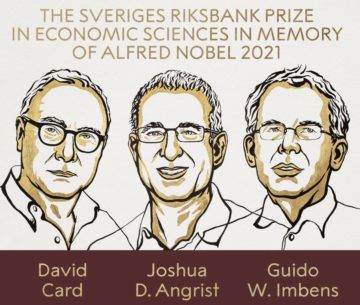

The Nobel Prize goes to David Card, Joshua Angrist and Guido Imbens. If you seek their monuments look around you. Almost all of the empirical work in economics that you read in the popular press (and plenty that doesn’t make the popular press) is due to analyzing natural experiments using techniques such as difference in differences, instrumental variables and regression discontinuity. The techniques are powerful but the ideas behind them are also understandable by the person in the street which has given economists a tremendous advantage when talking with the public. Take, for example, the famous minimum wage study of

The Nobel Prize goes to David Card, Joshua Angrist and Guido Imbens. If you seek their monuments look around you. Almost all of the empirical work in economics that you read in the popular press (and plenty that doesn’t make the popular press) is due to analyzing natural experiments using techniques such as difference in differences, instrumental variables and regression discontinuity. The techniques are powerful but the ideas behind them are also understandable by the person in the street which has given economists a tremendous advantage when talking with the public. Take, for example, the famous minimum wage study of  Early evening in late summer, the golden hour in the village of East Hampton. The surf is rough and pounds its regular measure on the shore. At the last driveway on a road ending at the beach, a cortège of cars—S.U.V.s, jeeps, candy-colored roadsters—pull up to the gate, sand crunching pleasantly under the tires. And out they come, face after famous face, burnished, expensively moisturized: Jerry Seinfeld, Jimmy Buffett, Anjelica Huston, Julianne Moore, Stevie Van Zandt, Alec Baldwin, Jon Bon Jovi. They all wear expectant, delighted-to-be-invited expressions. Through the gate, they mount a flight of stairs to the front door and walk across a vaulted living room to a fragrant back yard, where a crowd is circulating under a tent in the familiar high-life way, regarding the territory, pausing now and then to accept refreshments from a tray.

Early evening in late summer, the golden hour in the village of East Hampton. The surf is rough and pounds its regular measure on the shore. At the last driveway on a road ending at the beach, a cortège of cars—S.U.V.s, jeeps, candy-colored roadsters—pull up to the gate, sand crunching pleasantly under the tires. And out they come, face after famous face, burnished, expensively moisturized: Jerry Seinfeld, Jimmy Buffett, Anjelica Huston, Julianne Moore, Stevie Van Zandt, Alec Baldwin, Jon Bon Jovi. They all wear expectant, delighted-to-be-invited expressions. Through the gate, they mount a flight of stairs to the front door and walk across a vaulted living room to a fragrant back yard, where a crowd is circulating under a tent in the familiar high-life way, regarding the territory, pausing now and then to accept refreshments from a tray.