by Cynthia Haven

“People in the know know him.” That’s what his English translator, Peter Constantine, told me. Grzegorz Kwiatkowski is becoming an important poetic voice from today’s Poland, with six volumes of poetry, and translated editions on the way. His translator added, “He has a strange poetic voice, very original and stark.”

“People in the know know him.” That’s what his English translator, Peter Constantine, told me. Grzegorz Kwiatkowski is becoming an important poetic voice from today’s Poland, with six volumes of poetry, and translated editions on the way. His translator added, “He has a strange poetic voice, very original and stark.”

Grzegorz is also a celebrated musician: his internationally known post-rock band Trupa Trupa has been featured on NPR, The Guardian, Rolling Stone, and elsewhere. He has called his music a “vital pessimism” which shows the “rather dark and rather frightening sides of human nature.”

He grew up in Gdańsk, in the shadow of a family marred by his grandfather’s internment in a concentration camp. “My grandfather and his sister were both in the camps. This experience buried them,” he said. “After the war, she went crazy and he became a quiet, hidden man.”

His minimalist poems explore not only conflicted pasts of Eastern Europe – for example, the Nazi euthanasia program – but also the paradoxes of contemporary genocides –Rwanda, for instance. His poems have been perceived as quasi-testimonies, provocative and lyrical utterances delivered by the dead.

Yale critic Richard Deming said that Kwiatkowski’s work “reveals that the unforgettable is also the undeniable. Is it beautiful? I say it is powerfully necessary, unrelentingly direct. I say it burns.” Read more »

Most cinemas have been open for some time where I live. After having been indoors in restaurants and bars a few times, I was slowly reintroduced to the pleasures of sharing a space with strangers. And finally it felt like the right moment to, once again, set foot in a cinema.

Most cinemas have been open for some time where I live. After having been indoors in restaurants and bars a few times, I was slowly reintroduced to the pleasures of sharing a space with strangers. And finally it felt like the right moment to, once again, set foot in a cinema. Among other members in the Economics faculty at Cambridge, there was the great Italian scholar, Piero Sraffa. He was administratively the professor-in-charge of us, graduate students. So I met him a few times in that connection, but never quite intellectually engaged with him, partly because by that time he was a bit reclusive and did not teach classes or attend seminars; but also because I was so much in awe of his reputation in areas where I had little expertise. His work in Economics was path-breaking in taking price theory to its classical roots, he had an influence on Wittgenstein’s philosophy (which the latter acknowledged), and he was a close friend of the Italian Marxist thinker, Antonio Gramsci (when the latter was jailed by Mussolini in 1926, Sraffa used to regularly supply him with books and even pen and paper, with which Gramsci wrote his famous Prison Notebooks, procured by Sraffa from the prison authorities after Gramsci’s death in 1937).

Among other members in the Economics faculty at Cambridge, there was the great Italian scholar, Piero Sraffa. He was administratively the professor-in-charge of us, graduate students. So I met him a few times in that connection, but never quite intellectually engaged with him, partly because by that time he was a bit reclusive and did not teach classes or attend seminars; but also because I was so much in awe of his reputation in areas where I had little expertise. His work in Economics was path-breaking in taking price theory to its classical roots, he had an influence on Wittgenstein’s philosophy (which the latter acknowledged), and he was a close friend of the Italian Marxist thinker, Antonio Gramsci (when the latter was jailed by Mussolini in 1926, Sraffa used to regularly supply him with books and even pen and paper, with which Gramsci wrote his famous Prison Notebooks, procured by Sraffa from the prison authorities after Gramsci’s death in 1937). Genevieve Lloyd has done much to promote serious engagement with Baruch Spinoza and has demonstrated many ways in which Spinoza can inform and challenge current debates in the philosophical mainstream. In her article in this issue, Lloyd invites us to challenge the simplistic caricature of Spinoza as a paradigm ‘rationalist’, thus providing us with rich insights into the subtleties of Spinoza’s naturalist view on minds, knowledge, and reason. This more accurate picture, however, offers a striking similarity to the work of Daniel Dennett. Indeed, Spinoza and Dennett are alike in sharing their fervent opposition to Descartes’ conception of mind and body.

Genevieve Lloyd has done much to promote serious engagement with Baruch Spinoza and has demonstrated many ways in which Spinoza can inform and challenge current debates in the philosophical mainstream. In her article in this issue, Lloyd invites us to challenge the simplistic caricature of Spinoza as a paradigm ‘rationalist’, thus providing us with rich insights into the subtleties of Spinoza’s naturalist view on minds, knowledge, and reason. This more accurate picture, however, offers a striking similarity to the work of Daniel Dennett. Indeed, Spinoza and Dennett are alike in sharing their fervent opposition to Descartes’ conception of mind and body. Lloyd [2021] herself alludes to Dennett when she suggests that a serious engagement with Spinoza might allow us to provide an alternative framing of the problem of consciousness—one that replaces the current metaphors with what Dennett [1991: 455] would describe as novel ‘tools of thought’. While Lloyd [2017] has addressed the connection between Spinoza and the problem of consciousness in a previous publication, little has been made of the connection between these two Anti-Cartesian conceptions of the mind.

Lloyd [2021] herself alludes to Dennett when she suggests that a serious engagement with Spinoza might allow us to provide an alternative framing of the problem of consciousness—one that replaces the current metaphors with what Dennett [1991: 455] would describe as novel ‘tools of thought’. While Lloyd [2017] has addressed the connection between Spinoza and the problem of consciousness in a previous publication, little has been made of the connection between these two Anti-Cartesian conceptions of the mind. Testimony by former Facebook employee Frances Haugen, who holds a degree from Harvard Business School, and a series in the Wall Street Journal have left many, including

Testimony by former Facebook employee Frances Haugen, who holds a degree from Harvard Business School, and a series in the Wall Street Journal have left many, including  If you are concerned about the well-being of the United States and interested in what the country could do to help itself, stop what you are doing and read historian Geoffrey Kabaservice’s superb 2012 book,

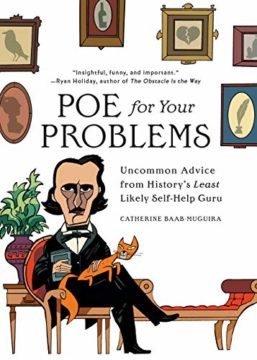

If you are concerned about the well-being of the United States and interested in what the country could do to help itself, stop what you are doing and read historian Geoffrey Kabaservice’s superb 2012 book,  “Live your best life.” It’s one of the most common, yet worthless, aphorisms offered today. Chipper, insipid, and surprisingly relativistic (it fits arsonists as well as anybody), this meaningless maxim is the Tic-Tac of modern aspiration, boasting all the nuance and depth of Target word-art or pastel Instagram posts. Fed up with such drivel, and equally skeptical of the therapy-industrial complex, writer Catherine Baab-Muguira urges us in her debut book of nonfiction to take the exact opposite tack: to live our worst life instead.

“Live your best life.” It’s one of the most common, yet worthless, aphorisms offered today. Chipper, insipid, and surprisingly relativistic (it fits arsonists as well as anybody), this meaningless maxim is the Tic-Tac of modern aspiration, boasting all the nuance and depth of Target word-art or pastel Instagram posts. Fed up with such drivel, and equally skeptical of the therapy-industrial complex, writer Catherine Baab-Muguira urges us in her debut book of nonfiction to take the exact opposite tack: to live our worst life instead. Towards what seemed like the halfway point of his show in London last night, Dave Chappelle announced to the crowd he was going to tell us something he was refusing to tell the media. He wanted us to know, he said while looking sadly at the floor, that his quarrel was not with the gay or the trans communities . No, no. Looking up and raising an index finger, he explained: ‘I’m fighting a corporate agenda that needs to be addressed.’ Thinking we still had another hour of the show to go, we cheered. ‘You fight those corporate vampires, Dave!’ we thought. He then let us know, whenever it was possible, that we should be kind to one another. Very shortly after that he raised his thumbs aloft and walked off stage: 45 minutes. Friday night tickets are £160. You show those corporate vamp… oh.

Towards what seemed like the halfway point of his show in London last night, Dave Chappelle announced to the crowd he was going to tell us something he was refusing to tell the media. He wanted us to know, he said while looking sadly at the floor, that his quarrel was not with the gay or the trans communities . No, no. Looking up and raising an index finger, he explained: ‘I’m fighting a corporate agenda that needs to be addressed.’ Thinking we still had another hour of the show to go, we cheered. ‘You fight those corporate vampires, Dave!’ we thought. He then let us know, whenever it was possible, that we should be kind to one another. Very shortly after that he raised his thumbs aloft and walked off stage: 45 minutes. Friday night tickets are £160. You show those corporate vamp… oh. C. P. Chandrasekhar and Jayati Ghosh in Boston Review ( Image: James Robertson/Jubilee Debt Campaign):

C. P. Chandrasekhar and Jayati Ghosh in Boston Review ( Image: James Robertson/Jubilee Debt Campaign): David M. Perry and Matthew Gabriele over at CNN:

David M. Perry and Matthew Gabriele over at CNN: Sophie Elmhirst in The Guardian (Illustration by Pete Reynolds):

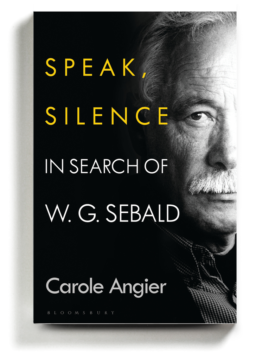

Sophie Elmhirst in The Guardian (Illustration by Pete Reynolds): W.G. Sebald is probably the most revered German writer of the second half of the 20th century. His best-known books — “The Emigrants,” “The Rings of Saturn,” “Austerlitz,” published here between 1997 and 2001 — are famously difficult to categorize.

W.G. Sebald is probably the most revered German writer of the second half of the 20th century. His best-known books — “The Emigrants,” “The Rings of Saturn,” “Austerlitz,” published here between 1997 and 2001 — are famously difficult to categorize. Eliot’s humanism tends to inspire awe in her readers. “She seems to care for people, indiscriminately and in their entirety, as it was once said God did,” wrote Zadie Smith in a 2008 essay on Middlemarch. As it was once said God did. My first thought is of Middlemarch’s omniscient narrator: sage, a little sarcastic, a little judgemental as she tunes into the thoughts of each character, catching them in the act of realising something about themselves.

Eliot’s humanism tends to inspire awe in her readers. “She seems to care for people, indiscriminately and in their entirety, as it was once said God did,” wrote Zadie Smith in a 2008 essay on Middlemarch. As it was once said God did. My first thought is of Middlemarch’s omniscient narrator: sage, a little sarcastic, a little judgemental as she tunes into the thoughts of each character, catching them in the act of realising something about themselves.