Bryan VanDyke in The Millions:

Some years ago, I attended a conference featuring boldface names and their thoughts on the topic of the essay as art. At 39, I’d written three failed novels, and essays felt like the last form left to me. I was desperate for tips, tricks, and whatever writerly chum they throw to audiences at events like these.

Some years ago, I attended a conference featuring boldface names and their thoughts on the topic of the essay as art. At 39, I’d written three failed novels, and essays felt like the last form left to me. I was desperate for tips, tricks, and whatever writerly chum they throw to audiences at events like these.

“An essay,” said Philip Lopate on the day of the conference, “is an invitation to think alongside me.”

I jotted his words in a Moleskine notebook and have been turning them over in my head and on the page ever since. The best essays are trips to terra nova, yes; but at heart, all essays depend on a simple sense of camaraderie. From the first word to the last, the writer of an essay is a guide, even if the piece never gets out of first gear. Each essay is a fellowship.

By Lopate’s definition, there’s no better essayist than Annie Dillard. Her thoughts go places no one else can see. Following in her path, you can sip the cold fire of eternity, cheat death in a stunt plane, or trace God’s name in sand, salt, or cloud. She didn’t invent the essay. Her most famous work isn’t classified as an essay. But in the cosmos of essayists, there’s Annie Dillard, and there’s everyone else.

More here.

The arrow of time — all the ways in which the past differs from the future — is a fascinating subject because it connects everyday phenomena (memory, aging, cause and effect) to deep questions in physics and philosophy. At its heart is the fact that entropy increases over time, which in turn can be traced to special conditions in the early universe. David Wallace is one of the world’s leading philosophers working on the foundations of physics, including space and time as well as quantum mechanics. We talk about how increasing entropy gives rise to the arrow of time, and what it is about the early universe that makes this happen. Then we cannot help but connecting this story to features of the Many-Worlds (Everett) interpretation of quantum mechanics.

The arrow of time — all the ways in which the past differs from the future — is a fascinating subject because it connects everyday phenomena (memory, aging, cause and effect) to deep questions in physics and philosophy. At its heart is the fact that entropy increases over time, which in turn can be traced to special conditions in the early universe. David Wallace is one of the world’s leading philosophers working on the foundations of physics, including space and time as well as quantum mechanics. We talk about how increasing entropy gives rise to the arrow of time, and what it is about the early universe that makes this happen. Then we cannot help but connecting this story to features of the Many-Worlds (Everett) interpretation of quantum mechanics. Multilateralism has been on the defensive in recent years. In a global setting that is more multipolar than multilateral, competition between states seems to prevail over cooperation nowadays. However, the recent global agreement to reform international corporate taxation is welcome proof that multilateralism is not dead.

Multilateralism has been on the defensive in recent years. In a global setting that is more multipolar than multilateral, competition between states seems to prevail over cooperation nowadays. However, the recent global agreement to reform international corporate taxation is welcome proof that multilateralism is not dead. It is 1966 and I am sitting on a stool at the Burger King on Merritt Island, Florida, eating French fries. My view is Highway 520 and the cars speeding up to the rare stoplight just beyond where I sit. My father, my sister, and I have been to Cocoa Beach to swim and are on our way home. I always beg to stop at the Burger King. I am always famished after swimming and there is nowhere to eat on the beach. Also, we are not a fast food family so this is a treat, something my mother, who never goes to the beach, does not know about. I love how, after being at the beach, the French fries taste doubly salty.

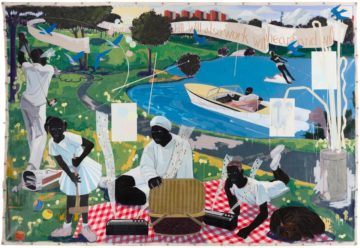

It is 1966 and I am sitting on a stool at the Burger King on Merritt Island, Florida, eating French fries. My view is Highway 520 and the cars speeding up to the rare stoplight just beyond where I sit. My father, my sister, and I have been to Cocoa Beach to swim and are on our way home. I always beg to stop at the Burger King. I am always famished after swimming and there is nowhere to eat on the beach. Also, we are not a fast food family so this is a treat, something my mother, who never goes to the beach, does not know about. I love how, after being at the beach, the French fries taste doubly salty. For the first thirty years of his career, Kerry James Marshall was a successful but little known artist. His figurative paintings, drawings, sculptures, photographs, and videos appeared in gallery and museum shows here and abroad, and selling them was never a problem. He won awards, residencies, and grants, including a MacArthur Fellowship in 1997, but in the contemporary-art world, which started to look more closely at Black artists in the nineties, Marshall was an outlier, and happy to be one. He had an unshakable confidence in himself as an artist, and the undistracted solitude of his practice allowed him to spend most of his time in the studio. The curator Helen Molesworth told me that during the three years it took to put together “Mastry,” Marshall’s first major retrospective in the United States, which opened in 2016 at the Museum of Contemporary Art Chicago and travelled to the Metropolitan Museum of Art and the Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles, “there were still people in the art world who didn’t know who he was.”

For the first thirty years of his career, Kerry James Marshall was a successful but little known artist. His figurative paintings, drawings, sculptures, photographs, and videos appeared in gallery and museum shows here and abroad, and selling them was never a problem. He won awards, residencies, and grants, including a MacArthur Fellowship in 1997, but in the contemporary-art world, which started to look more closely at Black artists in the nineties, Marshall was an outlier, and happy to be one. He had an unshakable confidence in himself as an artist, and the undistracted solitude of his practice allowed him to spend most of his time in the studio. The curator Helen Molesworth told me that during the three years it took to put together “Mastry,” Marshall’s first major retrospective in the United States, which opened in 2016 at the Museum of Contemporary Art Chicago and travelled to the Metropolitan Museum of Art and the Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles, “there were still people in the art world who didn’t know who he was.” J

J Ever since 1796, when English scientist and physician Edward Jenner successfully inoculated an eight-year-old boy with cowpox to protect him from smallpox, vaccines have been a key tool for preventing disease. From smallpox to polio, diphtheria to COVID-19, vaccines have prevented more deaths from infectious disease than any other medical treatment.

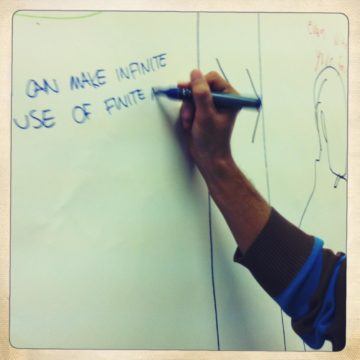

Ever since 1796, when English scientist and physician Edward Jenner successfully inoculated an eight-year-old boy with cowpox to protect him from smallpox, vaccines have been a key tool for preventing disease. From smallpox to polio, diphtheria to COVID-19, vaccines have prevented more deaths from infectious disease than any other medical treatment. Luxuriating in human ignorance was once a classy fad. Overeducated literary types would read Schopenhauer and Kierkegaard and Dostoevsky and Nietzsche, and soak themselves in the quite intelligent conclusion that ultimate reality cannot be known by Terran primates, no matter how many words they use. They would dwell on the suspicion that anything these primates conceive will be skewed by social, sexual, economic, and religious preconceptions and biases; that the very idea that there is an ultimate reality, with a definable character, may very well be a superstition forced upon us by so humble a force as grammar; that in an absurd life bounded on all sides by illusion, the very best a Terran primate might do is to at least be honest with itself, and compassionate toward its colleagues, so that we might all get through this thing together.

Luxuriating in human ignorance was once a classy fad. Overeducated literary types would read Schopenhauer and Kierkegaard and Dostoevsky and Nietzsche, and soak themselves in the quite intelligent conclusion that ultimate reality cannot be known by Terran primates, no matter how many words they use. They would dwell on the suspicion that anything these primates conceive will be skewed by social, sexual, economic, and religious preconceptions and biases; that the very idea that there is an ultimate reality, with a definable character, may very well be a superstition forced upon us by so humble a force as grammar; that in an absurd life bounded on all sides by illusion, the very best a Terran primate might do is to at least be honest with itself, and compassionate toward its colleagues, so that we might all get through this thing together. When King Midas asked Silenus what the best thing for man is, Silenus replied, “It is better not to have been born at all. The next best thing for man would be to die quickly.”

When King Midas asked Silenus what the best thing for man is, Silenus replied, “It is better not to have been born at all. The next best thing for man would be to die quickly.”

Sughra Raza. Untitled. April 2021

Sughra Raza. Untitled. April 2021

A rose is a rose is…well, you know. Botanically, a rose is the flower of a plant in the genus Rosa in the family Rosaceae. But roses carry the weight of so much symbolism that a rose is seldom only a rose.

A rose is a rose is…well, you know. Botanically, a rose is the flower of a plant in the genus Rosa in the family Rosaceae. But roses carry the weight of so much symbolism that a rose is seldom only a rose.