Beth Kephart in Cleaver:

Writing funny, especially in memoir, is a surprisingly recherché talent. Every spring semester at the University of Pennsylvania, where I teach memoir, the ratio of funny submissions to not-funny submissions is, on average, one: everything else. This semester our funny was the work of Jonathan, who had me choking on my chortles at 4 a.m., as I read lines like these:

Writing funny, especially in memoir, is a surprisingly recherché talent. Every spring semester at the University of Pennsylvania, where I teach memoir, the ratio of funny submissions to not-funny submissions is, on average, one: everything else. This semester our funny was the work of Jonathan, who had me choking on my chortles at 4 a.m., as I read lines like these:

My mother dresses me. Everything from purchasing the clothes to what I’d be wearing that day is her decision. I don’t particularly care—after all, I have something to wear and it’s comfortable and so be it. I imagine though that this becomes a chore for her: young children grow quickly, which means that old clothes became too small, too quickly. The solution, obviously, is to buy a size or two larger and let the kid grow into it. My shirts get so big that at times they stretch to my knees. This stroke of insight and ingenuity is well received by my peers and classmates alike.

“Why are you wearing a dress? Are you a GIRL?”

Jonathan is an unassuming writer—a non-writer, he claimed, choosing (for reasons that remain beyond my reach, since he did all the work and then some) to audit the class. But he had made us laugh out loud during COVID lockdown, inside our Zoom boxes, where he appeared against a borrowed backdrop so that we would not be exposed to the ramshackle of his purportedly unkempt habitat.

More here.

It looked like a tiny shrine on the forest floor: Bare ground clear of debris. Two walls of sticks, bending towards one another. Blue feathers and bottle caps arranged in a wide arc. And a small plastic doll, splayed in the center of the structure, eyes wide and mouth open in a plastic scream.

It looked like a tiny shrine on the forest floor: Bare ground clear of debris. Two walls of sticks, bending towards one another. Blue feathers and bottle caps arranged in a wide arc. And a small plastic doll, splayed in the center of the structure, eyes wide and mouth open in a plastic scream. A

A  ROBERT WALSER WAS A SWISS WRITER of the early twentieth century who wanted very much to be a German writer. He walked and walked more than he wrote and wrote, covering thousands of miles in his lifetime, albeit within limited territory. In the beginning his garb was clownish—“a wretched bright yellow midsummer suit, light dancing shoes, an intentionally vulgar, insolent, foolish hat”—near the end a motley of patched rags, and at the very end a shabby but proper suit and overcoat, his death duds when he collapsed in 1956 in the snow near the mental asylum where he had resided for twenty-three years, years in which he wrote nothing.

ROBERT WALSER WAS A SWISS WRITER of the early twentieth century who wanted very much to be a German writer. He walked and walked more than he wrote and wrote, covering thousands of miles in his lifetime, albeit within limited territory. In the beginning his garb was clownish—“a wretched bright yellow midsummer suit, light dancing shoes, an intentionally vulgar, insolent, foolish hat”—near the end a motley of patched rags, and at the very end a shabby but proper suit and overcoat, his death duds when he collapsed in 1956 in the snow near the mental asylum where he had resided for twenty-three years, years in which he wrote nothing. In 2014, music fans and critics began paying close attention to a mysterious group of artists who’d started releasing tracks online. They were part of PC Music, a loose electronic-music collective that functioned more like a conceptual-art project. Led by a young, inventive producer from London named A. G. Cook, PC Music, and its affiliates, rejected a dark, murky strain of underground electronic music that was beloved at the time. Instead, they latched onto the most exuberant and absurd elements of pop, making cutesy, theatrical songs that sounded a bit like children’s music, but with an unsettling aftertaste. If mainstream pop is designed to make people feel as if they’re on common ground with all of humanity, this music made listeners feel like they were in on a very specific joke. In a Pitchfork article titled “PC Music’s Twisted Electronic Pop: A User’s Manual,” one critic wrote, “The shadowy operation and its bewildering brand of hyper-pop have been everywhere in the past few months . . . and its influence seems to be growing on a daily basis.”

In 2014, music fans and critics began paying close attention to a mysterious group of artists who’d started releasing tracks online. They were part of PC Music, a loose electronic-music collective that functioned more like a conceptual-art project. Led by a young, inventive producer from London named A. G. Cook, PC Music, and its affiliates, rejected a dark, murky strain of underground electronic music that was beloved at the time. Instead, they latched onto the most exuberant and absurd elements of pop, making cutesy, theatrical songs that sounded a bit like children’s music, but with an unsettling aftertaste. If mainstream pop is designed to make people feel as if they’re on common ground with all of humanity, this music made listeners feel like they were in on a very specific joke. In a Pitchfork article titled “PC Music’s Twisted Electronic Pop: A User’s Manual,” one critic wrote, “The shadowy operation and its bewildering brand of hyper-pop have been everywhere in the past few months . . . and its influence seems to be growing on a daily basis.” E

E In the darkness of her small bedroom in Peru’s Sacred Valley of the Incas, Sara Qquehuarucho Zamalloa packed her bag, thoughts racing: Would the weather be good? Would the team be friendly? Would she encounter park rangers with bad attitudes toward women? Would her mum, who suffers from chronic pain, be okay while she was gone?

In the darkness of her small bedroom in Peru’s Sacred Valley of the Incas, Sara Qquehuarucho Zamalloa packed her bag, thoughts racing: Would the weather be good? Would the team be friendly? Would she encounter park rangers with bad attitudes toward women? Would her mum, who suffers from chronic pain, be okay while she was gone? The class structure of Western society has gotten scrambled over the past few decades. It used to be straightforward: You had the rich, who joined country clubs and voted Republican; the working class, who toiled in the factories and voted Democratic; and, in between, the mass suburban middle class. We had a clear idea of what class conflict, when it came, would look like—members of the working classes would align with progressive intellectuals to take on the capitalist elite.

The class structure of Western society has gotten scrambled over the past few decades. It used to be straightforward: You had the rich, who joined country clubs and voted Republican; the working class, who toiled in the factories and voted Democratic; and, in between, the mass suburban middle class. We had a clear idea of what class conflict, when it came, would look like—members of the working classes would align with progressive intellectuals to take on the capitalist elite. By the summer of 1981, I had completed my PhD under Steve’s supervision and was starting a junior faculty position at Harvard. I knew that my parents, who were visiting, would enjoy meeting Steve and Louise, so we all had dinner together in my backyard. Realizing how much it would please my parents, Steve made some kind remarks about me during dinner. But the most memorable moment was when we were discussing how to make ice cream, and Steve expressed puzzlement over why one adds salt to the ice-cream maker. My Dad, who was not a scientist, helpfully suggested, “Isn’t it to lower the melting point of the ice, so the ice cream will be cold enough to solidify?” “Of course!” Steve replied, slapping his forehead. “I never understood that before. Thank you!” And for the rest of his life, my Dad would relish the time he gave the great Steven Weinberg a physics lesson.

By the summer of 1981, I had completed my PhD under Steve’s supervision and was starting a junior faculty position at Harvard. I knew that my parents, who were visiting, would enjoy meeting Steve and Louise, so we all had dinner together in my backyard. Realizing how much it would please my parents, Steve made some kind remarks about me during dinner. But the most memorable moment was when we were discussing how to make ice cream, and Steve expressed puzzlement over why one adds salt to the ice-cream maker. My Dad, who was not a scientist, helpfully suggested, “Isn’t it to lower the melting point of the ice, so the ice cream will be cold enough to solidify?” “Of course!” Steve replied, slapping his forehead. “I never understood that before. Thank you!” And for the rest of his life, my Dad would relish the time he gave the great Steven Weinberg a physics lesson. 100 years ago yesterday — on July 29, 1921 — Adolph Hitler was elected leader of the Nationalist Socialist German Workers’ Party, later known as the Nazi Party. The combustible Army corporal succeeded the party’s original leader, Anton Drexler, whom Hitler originally been sent to spy on, but whose ideas he came to admire (he may even have shaved his mustache to emulate his predecessor). The 533-1 delegate vote set in motion a series of events that would dominate the next two and a half decades of world history.

100 years ago yesterday — on July 29, 1921 — Adolph Hitler was elected leader of the Nationalist Socialist German Workers’ Party, later known as the Nazi Party. The combustible Army corporal succeeded the party’s original leader, Anton Drexler, whom Hitler originally been sent to spy on, but whose ideas he came to admire (he may even have shaved his mustache to emulate his predecessor). The 533-1 delegate vote set in motion a series of events that would dominate the next two and a half decades of world history. W

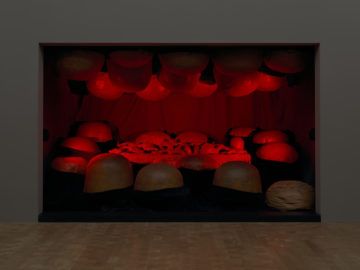

W The list of mycologists whose names are known beyond their fungal field is short, and at its apex is Paul Stamets. Educated in, and a longtime resident of, the mossy, moldy, mushy Pacific Northwest region, Stamets has made numerous contributions over the past several decades— perhaps the best summation of which can be found in his 2005 book Mycelium Running: How Mushrooms Can Help Save the World. But now he is looking beyond Earth to discover new ways that mushrooms can help with the exploration of space.

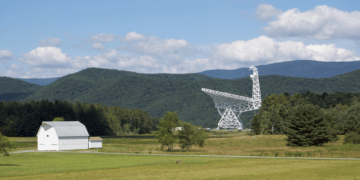

The list of mycologists whose names are known beyond their fungal field is short, and at its apex is Paul Stamets. Educated in, and a longtime resident of, the mossy, moldy, mushy Pacific Northwest region, Stamets has made numerous contributions over the past several decades— perhaps the best summation of which can be found in his 2005 book Mycelium Running: How Mushrooms Can Help Save the World. But now he is looking beyond Earth to discover new ways that mushrooms can help with the exploration of space. The Log Lady of the Quiet Zone lived a few miles away and had the mysterious power to “detect” WiFi, cell signals, and other forms of electromagnetic radiation. I was told I might find the Log Lady at church—perhaps the only church in America quiet enough for her to attend.

The Log Lady of the Quiet Zone lived a few miles away and had the mysterious power to “detect” WiFi, cell signals, and other forms of electromagnetic radiation. I was told I might find the Log Lady at church—perhaps the only church in America quiet enough for her to attend. I WONDER HOW people will think of psychoanalysis after they see the show “Louise Bourgeois, Freud’s Daughter,” currently at the Jewish Museum in New York. Will it rise in their esteem, having fallen to the level of a silly, obsolete science, a worn-out, clichéd set of interpretations? Bourgeois’s relationship to psychoanalysis is rich, layered, and, importantly, long, as psychoanalysis is wont to be: beginning in 1951 with her treatment following her father’s death, lasting until 1985 with her psychoanalyst’s death. She calls it “a jip,” “a duty,” “a joke,” “a love affair,” “a bad dream,” “a pain in the neck,” and “my field of study.”1 It is, indeed, all of these things and more. And it is, in ways I think have been neglected or rarely glimpsed, also sculptural.

I WONDER HOW people will think of psychoanalysis after they see the show “Louise Bourgeois, Freud’s Daughter,” currently at the Jewish Museum in New York. Will it rise in their esteem, having fallen to the level of a silly, obsolete science, a worn-out, clichéd set of interpretations? Bourgeois’s relationship to psychoanalysis is rich, layered, and, importantly, long, as psychoanalysis is wont to be: beginning in 1951 with her treatment following her father’s death, lasting until 1985 with her psychoanalyst’s death. She calls it “a jip,” “a duty,” “a joke,” “a love affair,” “a bad dream,” “a pain in the neck,” and “my field of study.”1 It is, indeed, all of these things and more. And it is, in ways I think have been neglected or rarely glimpsed, also sculptural.