Justin Rowlatt in BBC News:

Covid-19 was the big issue of 2020, there is no question about that. But I’m hoping that, by the end of 2021, the vaccines will have kicked in and we’ll be talking more about climate than the coronavirus. 2021 will certainly be a crunch year for tackling climate change. Antonio Guterres, the UN Secretary General, told me he thinks it is a “make or break” moment for the issue. So, in the spirit of New Year’s optimism, here’s why I believe 2021 could confound the doomsters and see a breakthrough in global ambition on climate.

Covid-19 was the big issue of 2020, there is no question about that. But I’m hoping that, by the end of 2021, the vaccines will have kicked in and we’ll be talking more about climate than the coronavirus. 2021 will certainly be a crunch year for tackling climate change. Antonio Guterres, the UN Secretary General, told me he thinks it is a “make or break” moment for the issue. So, in the spirit of New Year’s optimism, here’s why I believe 2021 could confound the doomsters and see a breakthrough in global ambition on climate.

In November 2021, world leaders will be gathering in Glasgow for the successor to the landmark Paris meeting of 2015. Paris was important because it was the first time virtually all the nations of the world came together to agree they all needed to help tackle the issue. The problem was the commitments countries made to cutting carbon emissions back then fell way short of the targets set by the conference. In Paris, the world agreed to avoid the worst impacts of climate change by trying to limit global temperature increases to 2C above pre-industrial levels by the end of the century. The aim was to keep the rise to 1.5C if at all possible. We are way off track. On current plans the world is expected to breach the 1.5C ceiling within 12 years or less and to hit 3C of warming by the end of the century. Under the terms of the Paris deal, countries promised to come back every five years and raise their carbon-cutting ambitions. That was due to happen in Glasgow in November 2020. The pandemic put paid to that and the conference was bumped forward to this year. So, Glasgow 2021 gives us a forum at which those carbon cuts can be ratcheted up.

More here.

In 1973, shortly after his last novel, like the others before it, was rejected by publishers, the Italian writer Guido Morselli shot himself in the head and died. He left several rejection letters on his desk, and a short note that read, “I bear no grudges.” It was the kind of gesture one of his protagonists might have performed—a show of ironic detachment that belied a deep and obvious pain. Morselli was sixty years old. Before returning to his family’s home in Varese and ending his life, he had been living in near-isolation for two decades, on a small property in Lombardy, near the Swiss-Italian border. There he tended to the land, made wine, and wrote books that faced diminishing odds of publication. The last one that he finished tells the story of an apocalyptic event in which all of humanity suddenly vanishes, leaving a single man as the world’s only witness.

In 1973, shortly after his last novel, like the others before it, was rejected by publishers, the Italian writer Guido Morselli shot himself in the head and died. He left several rejection letters on his desk, and a short note that read, “I bear no grudges.” It was the kind of gesture one of his protagonists might have performed—a show of ironic detachment that belied a deep and obvious pain. Morselli was sixty years old. Before returning to his family’s home in Varese and ending his life, he had been living in near-isolation for two decades, on a small property in Lombardy, near the Swiss-Italian border. There he tended to the land, made wine, and wrote books that faced diminishing odds of publication. The last one that he finished tells the story of an apocalyptic event in which all of humanity suddenly vanishes, leaving a single man as the world’s only witness. AB: Yes, indeed! I was there when Christof Koch, a cognitive neuroscientist of international renown, said that philosophers had made a good speculative start but scientists (he meant ‘we scientists’) are now doing the job properly. A view that betrays a deep-running ignorance of philosophy, in my opinion. Philosophy has a central role to play in cognitive science and philosophy of cognitive science still has a lot of work to do. In cognitive science, philosophers do vital work clarifying concepts (the conceptual toolbox of cognitive research is a mess) and showing how hypotheses and theories relate to one another – in short, showing how things, in the broadest sense of ‘things’, hang together, in the broadest sense of ‘hang together’, as the outstanding American philosopher Wilfred Sellars put it some decades ago. Philosophy of cognitive science is just a branch of philosophy of science, though the wide range of styles of explanation used by cognitive researchers, just to take one example, offer some special challenges.

AB: Yes, indeed! I was there when Christof Koch, a cognitive neuroscientist of international renown, said that philosophers had made a good speculative start but scientists (he meant ‘we scientists’) are now doing the job properly. A view that betrays a deep-running ignorance of philosophy, in my opinion. Philosophy has a central role to play in cognitive science and philosophy of cognitive science still has a lot of work to do. In cognitive science, philosophers do vital work clarifying concepts (the conceptual toolbox of cognitive research is a mess) and showing how hypotheses and theories relate to one another – in short, showing how things, in the broadest sense of ‘things’, hang together, in the broadest sense of ‘hang together’, as the outstanding American philosopher Wilfred Sellars put it some decades ago. Philosophy of cognitive science is just a branch of philosophy of science, though the wide range of styles of explanation used by cognitive researchers, just to take one example, offer some special challenges. We all know stereotypes about people from different countries; but we also recognize that there really are broad cultural differences between people who grow up in different societies. This raises a challenge when most psychological research is performed on a narrow and unrepresentative slice of the world’s population — a subset that has accurately been labeled as

We all know stereotypes about people from different countries; but we also recognize that there really are broad cultural differences between people who grow up in different societies. This raises a challenge when most psychological research is performed on a narrow and unrepresentative slice of the world’s population — a subset that has accurately been labeled as  We used to think, with good reason, that globalization had defanged national governments. Presidents cowered before the bond markets. Prime ministers ignored their country’s poor but never Standard & Poor’s. Finance ministers behaved like Goldman Sachs’s knaves and the International Monetary Fund’s satraps. Media moguls, oil men, and financiers, no less than left-wing critics of globalized capitalism, agreed that governments were no longer in control.

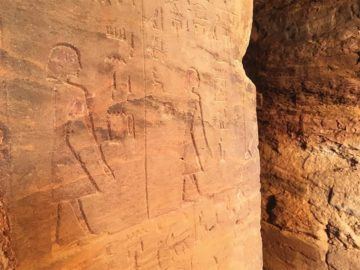

We used to think, with good reason, that globalization had defanged national governments. Presidents cowered before the bond markets. Prime ministers ignored their country’s poor but never Standard & Poor’s. Finance ministers behaved like Goldman Sachs’s knaves and the International Monetary Fund’s satraps. Media moguls, oil men, and financiers, no less than left-wing critics of globalized capitalism, agreed that governments were no longer in control. Centuries before Moses wandered in the “great and terrible wilderness” of the Sinai Peninsula, this triangle of desert wedged between Africa and Asia attracted speculators, drawn by rich mineral deposits hidden in the rocks. And it was on one of these expeditions, around 4,000 years ago, that some mysterious person or group took a bold step that, in retrospect, was truly revolutionary. Scratched on the wall of a mine is the very first attempt at something we use every day: the alphabet.

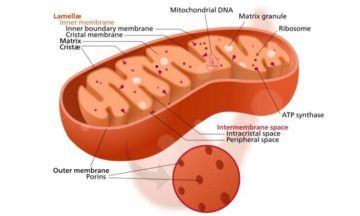

Centuries before Moses wandered in the “great and terrible wilderness” of the Sinai Peninsula, this triangle of desert wedged between Africa and Asia attracted speculators, drawn by rich mineral deposits hidden in the rocks. And it was on one of these expeditions, around 4,000 years ago, that some mysterious person or group took a bold step that, in retrospect, was truly revolutionary. Scratched on the wall of a mine is the very first attempt at something we use every day: the alphabet. Insofar as variants for mitochondrial disease are supposed to be rare in the genome, don’t think for even a minute that it can’t happen to you. In fact, the closer one looks at the full mitonuclear genomes of normal folks, the more one realizes that no one is actually normal—we are all, shall we say, temporarily asymptomatic. But in the fullness of time, many asymptomatics develop the hallmarks of

Insofar as variants for mitochondrial disease are supposed to be rare in the genome, don’t think for even a minute that it can’t happen to you. In fact, the closer one looks at the full mitonuclear genomes of normal folks, the more one realizes that no one is actually normal—we are all, shall we say, temporarily asymptomatic. But in the fullness of time, many asymptomatics develop the hallmarks of  The first thing I noticed about Le Cirque when I saw it at Pace was its clumsiness. The sculpture is comically, endearingly big: thirteen feet tall and almost a hundred feet in circumference, with elephant legs and zebra stripes like scribbles blown up a thousandfold. Since it didn’t have to compete for attention (the only other work in the exhibition was a 1968 maquette of Dubuffet’s equally sprawling Jardin d’émail), it seemed even bigger. As you walk through it, Le Cirque suggests the organic and the architectural all at once, as though the big top has somehow merged with the animals. For all its maker’s prestige, there’s still a whiff of third-grade daffiness in the air—I suppose there are higher compliments for the father of Art Brut, but I’m not sure what they’d be.

The first thing I noticed about Le Cirque when I saw it at Pace was its clumsiness. The sculpture is comically, endearingly big: thirteen feet tall and almost a hundred feet in circumference, with elephant legs and zebra stripes like scribbles blown up a thousandfold. Since it didn’t have to compete for attention (the only other work in the exhibition was a 1968 maquette of Dubuffet’s equally sprawling Jardin d’émail), it seemed even bigger. As you walk through it, Le Cirque suggests the organic and the architectural all at once, as though the big top has somehow merged with the animals. For all its maker’s prestige, there’s still a whiff of third-grade daffiness in the air—I suppose there are higher compliments for the father of Art Brut, but I’m not sure what they’d be. In the final days of the Second World War, a train loaded with relics of the collapsing Third Reich was speeding toward the Czech border when American pilots, flying P-47 fighters, spotted it and opened fire. The train ground to a halt in a forest, where German soldiers spirited the cargo away. They were pursued, not long afterward, by Gordon Gilkey, a young captain from Linn County, Oregon, who had been ordered to gather up all the Nazi propaganda and military art he could find. Gilkey tracked the smugglers to an abandoned woodcutter’s hut, where he pried up the floorboards and found what he was looking for: a collection of drawings and watercolors belonging to the German military’s high command. The cache had survived the strafing, only to be afflicted by mildew and a family of hungry mice. “They had eaten the ends off many pictures, large holes in a few, and gave all the cabin pictures an uneven deckle edge,” Gilkey wrote.

In the final days of the Second World War, a train loaded with relics of the collapsing Third Reich was speeding toward the Czech border when American pilots, flying P-47 fighters, spotted it and opened fire. The train ground to a halt in a forest, where German soldiers spirited the cargo away. They were pursued, not long afterward, by Gordon Gilkey, a young captain from Linn County, Oregon, who had been ordered to gather up all the Nazi propaganda and military art he could find. Gilkey tracked the smugglers to an abandoned woodcutter’s hut, where he pried up the floorboards and found what he was looking for: a collection of drawings and watercolors belonging to the German military’s high command. The cache had survived the strafing, only to be afflicted by mildew and a family of hungry mice. “They had eaten the ends off many pictures, large holes in a few, and gave all the cabin pictures an uneven deckle edge,” Gilkey wrote.

Every Democrat, and many independent voters, breathed an enormous sigh of relief when Joe Biden defeated Donald Trump in the November election. Now they are all nervously counting down the days (16) until the last of Trump’s frivolous lawsuits is dismissed, his minions’ stones bounce of the machinery of our electoral system, and Trump is finally evicted from the White House. Only then can we set about repairing the very significant damage that Trump and Trumpism have wrought upon our republican (small r) and democratic (small d) institutions.

Every Democrat, and many independent voters, breathed an enormous sigh of relief when Joe Biden defeated Donald Trump in the November election. Now they are all nervously counting down the days (16) until the last of Trump’s frivolous lawsuits is dismissed, his minions’ stones bounce of the machinery of our electoral system, and Trump is finally evicted from the White House. Only then can we set about repairing the very significant damage that Trump and Trumpism have wrought upon our republican (small r) and democratic (small d) institutions. Three times have we started doing philosophy, and three times has the enterprise come to a somewhat embarrassing end, being supplanted by other activities while failing anyway to deliver whatever goods it had promised. Each of those three times corresponds to a part of Stephen Gaukroger’s recent book The Failures of Philosophy, which I will be discussing here. In each of these three times, philosophy’s program was different: in Antiquity, it tied itself to the pursuit of the good life; after its revival in the European middle ages it obtained a status as the guardian of a fundamental science in the form of metaphysics; and when this metaphysical project disintegrated, it reinvented itself as the author of a meta-scientific theory of everything, eventually latching on to science in a last attempt at relevance.

Three times have we started doing philosophy, and three times has the enterprise come to a somewhat embarrassing end, being supplanted by other activities while failing anyway to deliver whatever goods it had promised. Each of those three times corresponds to a part of Stephen Gaukroger’s recent book The Failures of Philosophy, which I will be discussing here. In each of these three times, philosophy’s program was different: in Antiquity, it tied itself to the pursuit of the good life; after its revival in the European middle ages it obtained a status as the guardian of a fundamental science in the form of metaphysics; and when this metaphysical project disintegrated, it reinvented itself as the author of a meta-scientific theory of everything, eventually latching on to science in a last attempt at relevance.

For the past few years, I’ve been taking a fairly deep dive into attempting to understand the physical and ecological changes occurring on our planet and how these will affect human lives and civilization. As I’ve immersed myself in the science and the massive societal hurdles that stand in the way of an adequate response, I’m becoming aware that this exercise is changing me, too. I feel it inside my body, like a grey mass coalescing in my chest, sticking to everything, tugging against my heart and occluding my lungs. A couple of months ago, I decided to stop writing on this subject, to step away from these thoughts and concerns, because of their discomfiting darkness.

For the past few years, I’ve been taking a fairly deep dive into attempting to understand the physical and ecological changes occurring on our planet and how these will affect human lives and civilization. As I’ve immersed myself in the science and the massive societal hurdles that stand in the way of an adequate response, I’m becoming aware that this exercise is changing me, too. I feel it inside my body, like a grey mass coalescing in my chest, sticking to everything, tugging against my heart and occluding my lungs. A couple of months ago, I decided to stop writing on this subject, to step away from these thoughts and concerns, because of their discomfiting darkness.

If one enters the name “Ellen Page” into the search box at

If one enters the name “Ellen Page” into the search box at