Peter Gordon in The New Statesman:

Peter Gordon in The New Statesman:

Marxism has had a long and troubled relationship with religion. In 1843 the young Karl Marx wrote in a critical essay on German philosophy that religion is “the opium of the people”, a phrase that would eventually harden into official atheism for the communist movement, though it poorly represented the true opinions of its founding theorist. After all, Marx also wrote that religion is “the sentiment of a heartless world” and “the soul of soul-less conditions”, as if to suggest that even the most fantastical beliefs bear within themselves a protest against worldly suffering and a promise to redeem us from conditions that might otherwise appear beyond all possible change. To call Marx a “secularist”, then, may be too simple. Marx saw religion as an illusion, but he was too much the dialectician to claim that it could be simply waved aside without granting that even illusions point darkly toward truth.

In the 20th century the story grew even more conflicted. While Soviet Marxism turned with a vengeance against religious believers and sought to dismantle religious institutions, some theorists in the West who saw in Marxism a resource for philosophical speculation felt that dialectics itself demanded a more nuanced understanding of religion, so that its energies could be harnessed for a task of redemption that was directed not to the heavens but to the Earth. Especially in Weimar Germany, Marxism and religion often came together into an explosive combination. Creative and heterodox thinkers such as Ernst Bloch fashioned speculative philosophies of history to show that the religious past contained untapped sources of messianic hope that kept alive the “spirit of utopia” for modern-day revolution. Anarchists such as Gustav Landauer, a leader of post-1918 socialist uprising who was murdered by the far-right in Bavaria, strayed from Marxism into an exotic syncretism of mystical and revolutionary thought.

This strange chapter in the history of Marxist thought is of special relevance when we consider the ambivalent status of religion among the leading theorists associated with the Institute for Social Research, also known as the “Frankfurt School”.

More here.

Christopher Mackin and Richard May in The New Republic:

Christopher Mackin and Richard May in The New Republic: On the face of it, “Feline Philosophy” would seem like a departure for Gray — a playful exploration of what cats might have to teach humans in our never-ending quest to understand ourselves. But the book, in true Gray fashion, suggests that this very quest may itself be doomed. “Consciousness,” he writes, “has been overrated.” We get worried, anxious and miserable. Our vaunted capacity for abstract thought often gets us (or others) into trouble. We may be the only species to pursue scientific inquiry, but we’re also the only species that has consciously perpetrated genocides. Cats, unlike humans, don’t trick themselves into believing they are saviors, wreaking havoc in the process. “When cats are not hunting or mating, eating or playing, they sleep,” Gray writes. “There is no inner anguish that forces them into constant activity.”

On the face of it, “Feline Philosophy” would seem like a departure for Gray — a playful exploration of what cats might have to teach humans in our never-ending quest to understand ourselves. But the book, in true Gray fashion, suggests that this very quest may itself be doomed. “Consciousness,” he writes, “has been overrated.” We get worried, anxious and miserable. Our vaunted capacity for abstract thought often gets us (or others) into trouble. We may be the only species to pursue scientific inquiry, but we’re also the only species that has consciously perpetrated genocides. Cats, unlike humans, don’t trick themselves into believing they are saviors, wreaking havoc in the process. “When cats are not hunting or mating, eating or playing, they sleep,” Gray writes. “There is no inner anguish that forces them into constant activity.” Though wood still plays an important role in the construction of our homes — think two-by-four stud supports and plywood in walls, flooring and roofing — our eye most often falls on exteriors covered in synthetic materials like vinyl siding. Some playgrounds that once featured lots of wood now have our kids screaming atop molded plastic play sets. And thousands of readers will take in this review on a digital device, not on a sheet of paper made from dried wood pulp. In a world where wood is, if not absent, increasingly out of sight, British biologist Roland Ennos suggests we may not be paying enough attention to its importance. He contends that wood is not merely useful but central to human history. “It is the one material,” Ennos writes in “

Though wood still plays an important role in the construction of our homes — think two-by-four stud supports and plywood in walls, flooring and roofing — our eye most often falls on exteriors covered in synthetic materials like vinyl siding. Some playgrounds that once featured lots of wood now have our kids screaming atop molded plastic play sets. And thousands of readers will take in this review on a digital device, not on a sheet of paper made from dried wood pulp. In a world where wood is, if not absent, increasingly out of sight, British biologist Roland Ennos suggests we may not be paying enough attention to its importance. He contends that wood is not merely useful but central to human history. “It is the one material,” Ennos writes in “ The COVID-19 pandemic and recession caused devastating long-term unemployment and income losses for many, historic low interest rates for borrowers, and stock market highs for investors. Since NextAdvisor’s launch in June, we’ve followed along, looking to the experts and Americans directly affected to better understand — and share — how it all impacts your wallet. As we say goodbye to 2020, our writers and editors are reflecting on what we learned, and want to share some new practices we’re bringing into the new year. The coronavirus pandemic hit the United States in early March, resulting in millions of jobs lost, shuttered businesses, and deep uncertainty about the future. At its peak in April, the unemployment rate reached 14.7%. Today,

The COVID-19 pandemic and recession caused devastating long-term unemployment and income losses for many, historic low interest rates for borrowers, and stock market highs for investors. Since NextAdvisor’s launch in June, we’ve followed along, looking to the experts and Americans directly affected to better understand — and share — how it all impacts your wallet. As we say goodbye to 2020, our writers and editors are reflecting on what we learned, and want to share some new practices we’re bringing into the new year. The coronavirus pandemic hit the United States in early March, resulting in millions of jobs lost, shuttered businesses, and deep uncertainty about the future. At its peak in April, the unemployment rate reached 14.7%. Today,  “The Over-Soul” is my favorite essay, but Emerson is better known for “Self Reliance,” that famous paean to individualism. This is the one where Emerson declares that “[w]hoso would be a man must be nonconformist,” and disdains society as “a join-stock company, in which the members agree, for the better securing of his bread to each shareholder, to surrender the liberty and culture of the eater.” Again, the writing is seductive. For anyone adrift in the world, it is reassuring to hear that “[n]othing can bring you peace but yourself,” or that mental will can triumph over fate. It can really be this simple: “In the Will work and acquire, and thou hast chained the wheel of Chance, and shalt sit hereafter out of fear from her rotations.”

“The Over-Soul” is my favorite essay, but Emerson is better known for “Self Reliance,” that famous paean to individualism. This is the one where Emerson declares that “[w]hoso would be a man must be nonconformist,” and disdains society as “a join-stock company, in which the members agree, for the better securing of his bread to each shareholder, to surrender the liberty and culture of the eater.” Again, the writing is seductive. For anyone adrift in the world, it is reassuring to hear that “[n]othing can bring you peace but yourself,” or that mental will can triumph over fate. It can really be this simple: “In the Will work and acquire, and thou hast chained the wheel of Chance, and shalt sit hereafter out of fear from her rotations.” The coronavirus pandemic ignited at the end of 2019 and blazed across 2020. Many countries repeatedly contained it.

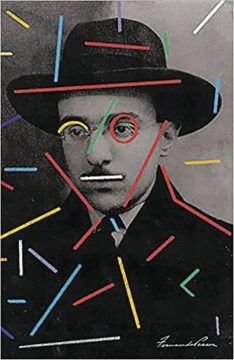

The coronavirus pandemic ignited at the end of 2019 and blazed across 2020. Many countries repeatedly contained it.  The Complete Works of Alberto Caeiro, translated by Margaret Jull Costa and Patricio Ferrari, presents the work of a complicated man. Caeiro was born in Lisbon in 1889, but he spent most of his life in the countryside. He received almost no formal education, but he was a passionate poet. At 25, he died of tuberculosis. Looking back, we can only be sure of one fact regarding Caeiro: He did not exist.

The Complete Works of Alberto Caeiro, translated by Margaret Jull Costa and Patricio Ferrari, presents the work of a complicated man. Caeiro was born in Lisbon in 1889, but he spent most of his life in the countryside. He received almost no formal education, but he was a passionate poet. At 25, he died of tuberculosis. Looking back, we can only be sure of one fact regarding Caeiro: He did not exist. Michael Baker figures he was the first public health expert in the world to talk about eliminating Covid-19, though he’s not sure why.

Michael Baker figures he was the first public health expert in the world to talk about eliminating Covid-19, though he’s not sure why. Since Rohr founded the Center for Action and Contemplation in 1987, his aim has been to revive the Christian contemplative tradition. For a growing number of Christendom’s defectors, his teachings have provided a bridge, even a destination. Through conferences, podcasts, dozens of books, a two-year curriculum called the Living School, and his newsletter, Rohr has become a leading voice for a growing population within American Christianity: those who were leaving the church not because they were done with Christianity, but because they were drawn to its more ancient, mystical expressions. In addition to the two thousand attendees from fifty states and fifteen countries, nearly three thousand more people from forty-two countries joined via webcast. I bought one of the last tickets before the conference sold out. To his credit, Rohr is quick to say that whatever popularity he enjoys is not because of himself—“God deliberately made me not so good-looking. I’m short and dumpy, a B student . . . and I don’t think I’m a saint”—but because he speaks on behalf of what he calls the perennial tradition, a lineage rooted in Christianity but that he says is present in all faiths.

Since Rohr founded the Center for Action and Contemplation in 1987, his aim has been to revive the Christian contemplative tradition. For a growing number of Christendom’s defectors, his teachings have provided a bridge, even a destination. Through conferences, podcasts, dozens of books, a two-year curriculum called the Living School, and his newsletter, Rohr has become a leading voice for a growing population within American Christianity: those who were leaving the church not because they were done with Christianity, but because they were drawn to its more ancient, mystical expressions. In addition to the two thousand attendees from fifty states and fifteen countries, nearly three thousand more people from forty-two countries joined via webcast. I bought one of the last tickets before the conference sold out. To his credit, Rohr is quick to say that whatever popularity he enjoys is not because of himself—“God deliberately made me not so good-looking. I’m short and dumpy, a B student . . . and I don’t think I’m a saint”—but because he speaks on behalf of what he calls the perennial tradition, a lineage rooted in Christianity but that he says is present in all faiths. Since 2011, a monument to Martin Luther King, Jr., has sat across the water from the Jefferson Memorial, almost engaging it in a staring contest. The result is a rich spatial symbolism: two ways of seeing Christ duking it out. King saw Jesus in much the way that Douglass did: as a savior, a redeemer, and a liberator sorely degraded by those who claimed his name most loudly. During the Montgomery bus boycott, King reportedly carried a copy of “

Since 2011, a monument to Martin Luther King, Jr., has sat across the water from the Jefferson Memorial, almost engaging it in a staring contest. The result is a rich spatial symbolism: two ways of seeing Christ duking it out. King saw Jesus in much the way that Douglass did: as a savior, a redeemer, and a liberator sorely degraded by those who claimed his name most loudly. During the Montgomery bus boycott, King reportedly carried a copy of “ Most of the 74,222,957 Americans who voted to re-elect

Most of the 74,222,957 Americans who voted to re-elect  O

O