by Rafaël Newman

Arma virusque cano: Sing,

Arma virusque cano: Sing,

O Muse, through me, the wandering

Of something lowly, microscopic,

But found at both Poles, and each Tropic.

An opportunist virus, which

Is banished by mere soap (or bleach),

And yet has billions, masked, in arma,

Awaiting backup from Big Pharma!

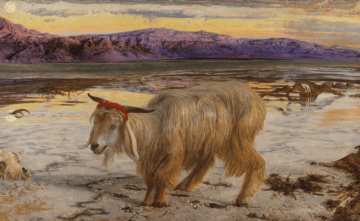

Now, whether to the Orient

The creature traces its descent,

Or simply sprang across the barrier

Which cordons beast from human carrier,

And might have done so anywhere

That folk are fond of carnal fare –

Yet from the hellish depths have risen

Those who would make of chance a prison:

Who’ve seized upon a place of birth

In any random plot of earth

To build a fable of malfeasance,

Of trade wars, tariff hikes, and treasons;

Who’ve leveraged the lockdown here

To redirect Our gen’ral fear

Towards a Them there, over yonder:

The fascist’s faithful first responder.

To counter which, we’ve cried, “Unite!

We’ll pledge ourselves to righteous fight

Against the foe that would divide us:

That dreary retrograde King Midas!

An alchemist à contresens

Who makes of merry gold mere dross;

Whose Internationale’s inverted,

Whose harmonies are disconcerted!

We’ll scotch the pestilential scourge

With martial pomp, not fun’ral dirge,

And then, our forces massed together,

We’ll end the plague, and change the weather!” Read more »

This Christmas, I stayed in a Marriott in the town where my kids live. Like most people, my business and personal travel has mostly ground to a halt in the last 9 months. So I was pleasantly surprised by the check-in experience the hotel provided me to allow for social distancing. I’m a long-time Marriot member and have their app on my phone. Using it, I was able to check-in ahead of time, and when my room was ready, they sent me a mobile key.

This Christmas, I stayed in a Marriott in the town where my kids live. Like most people, my business and personal travel has mostly ground to a halt in the last 9 months. So I was pleasantly surprised by the check-in experience the hotel provided me to allow for social distancing. I’m a long-time Marriot member and have their app on my phone. Using it, I was able to check-in ahead of time, and when my room was ready, they sent me a mobile key.  In the early months of 1966, whenever a familiar look of boredom settled in my mother’s eyes at the thought of cooking, I’d suggest, “Why don’t we go out for pizza?”

In the early months of 1966, whenever a familiar look of boredom settled in my mother’s eyes at the thought of cooking, I’d suggest, “Why don’t we go out for pizza?”

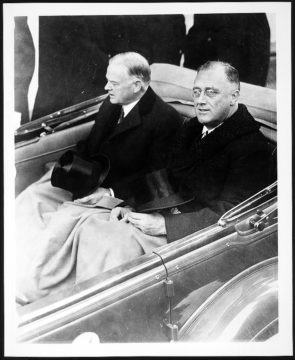

Adlai Stevenson, in the concession speech he gave after being thoroughly routed by Ike in the 1952 Election, referenced a possibly apocryphal quote by Abraham Lincoln: “He felt like a little boy who had stubbed his toe in the dark. He said that he was too old to cry, but it hurt too much to laugh.”

Adlai Stevenson, in the concession speech he gave after being thoroughly routed by Ike in the 1952 Election, referenced a possibly apocryphal quote by Abraham Lincoln: “He felt like a little boy who had stubbed his toe in the dark. He said that he was too old to cry, but it hurt too much to laugh.”

Although the literary theorist and anthropologist René Girard has many Silicon Valley disciples, surely the most notable of them is the German-born venture capitalist and founder of PayPal, Peter Thiel. A student of Girard’s while at Stanford in the late 1980s, Thiel would go on to report, in several interviews, and somewhat more sub-rosa in his 2014 book,

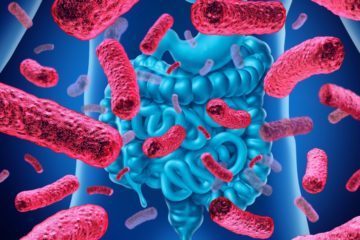

Although the literary theorist and anthropologist René Girard has many Silicon Valley disciples, surely the most notable of them is the German-born venture capitalist and founder of PayPal, Peter Thiel. A student of Girard’s while at Stanford in the late 1980s, Thiel would go on to report, in several interviews, and somewhat more sub-rosa in his 2014 book,  We are never alone. And by this statement, I do not intend to argue for existence of some supernatural entities, aliens or God. We are never alone because we all share our bodies with trillions of symbiotic microorganisms that perform various physiological functions crucial for our health. In fact, they may be responsible for even more than that. Here, I present a view that the symbiotic microbiota is an important part of the complex system constituting our consciousness. By consciousness, I mean the type called phenomenal consciousness (Block 2002) which stands for the subjective experience of what is it like to be someone (see Nagel 1974).

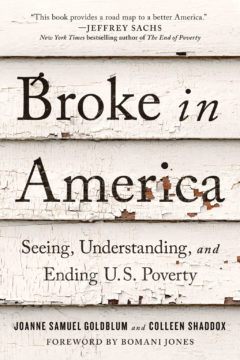

We are never alone. And by this statement, I do not intend to argue for existence of some supernatural entities, aliens or God. We are never alone because we all share our bodies with trillions of symbiotic microorganisms that perform various physiological functions crucial for our health. In fact, they may be responsible for even more than that. Here, I present a view that the symbiotic microbiota is an important part of the complex system constituting our consciousness. By consciousness, I mean the type called phenomenal consciousness (Block 2002) which stands for the subjective experience of what is it like to be someone (see Nagel 1974). When we speak to our sisters and brothers living in poverty in the United States, the confessional trope that describes so many dysfunctional relationships should be our opening line. “Poverty is a choice that the fortunate collectively make,” social worker Joanne Goldblum and journalist Colleen Shaddox write in

When we speak to our sisters and brothers living in poverty in the United States, the confessional trope that describes so many dysfunctional relationships should be our opening line. “Poverty is a choice that the fortunate collectively make,” social worker Joanne Goldblum and journalist Colleen Shaddox write in  The investigative journalist Gary Taubes is known for his painstakingly researched and withering demolitions of the “eat less, move more” diet orthodoxy, but his latest book is personal. The Case for Keto is aimed at “those of us who fatten easily”. Taubes locates himself in this beleaguered group, “despite an addiction to exercise for the better part of a decade” and a diet of “low-fat, mostly plant ‘healthy’ eating”. “I avoided avocados and peanut butter because they were high in fat and I thought of red meat, particularly steak and bacon, as an agent of premature death. I ate only the whites of egg.” Yet still he remained overweight.

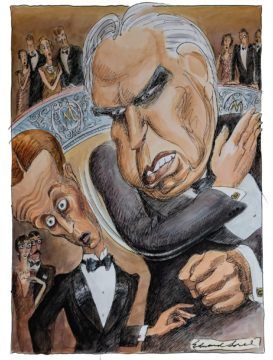

The investigative journalist Gary Taubes is known for his painstakingly researched and withering demolitions of the “eat less, move more” diet orthodoxy, but his latest book is personal. The Case for Keto is aimed at “those of us who fatten easily”. Taubes locates himself in this beleaguered group, “despite an addiction to exercise for the better part of a decade” and a diet of “low-fat, mostly plant ‘healthy’ eating”. “I avoided avocados and peanut butter because they were high in fat and I thought of red meat, particularly steak and bacon, as an agent of premature death. I ate only the whites of egg.” Yet still he remained overweight. Both grew up in the Midwest, both wrote novels that skewered the patriarchal, conformist towns where they were raised, and both shared the distinction of having churchmen condemn their books as “immoral.” They should have been friends, but by 1925, when Theodore Dreiser’s “An American Tragedy” was published, he and Sinclair Lewis were hoping to become the first American to win the Nobel Prize in Literature. Lewis had already produced “Main Street” in 1920, then followed it with “Babbitt,” “Arrowsmith,” “Elmer Gantry” and “Dodsworth” before the decade was even over. In 1930 the prize was his.

Both grew up in the Midwest, both wrote novels that skewered the patriarchal, conformist towns where they were raised, and both shared the distinction of having churchmen condemn their books as “immoral.” They should have been friends, but by 1925, when Theodore Dreiser’s “An American Tragedy” was published, he and Sinclair Lewis were hoping to become the first American to win the Nobel Prize in Literature. Lewis had already produced “Main Street” in 1920, then followed it with “Babbitt,” “Arrowsmith,” “Elmer Gantry” and “Dodsworth” before the decade was even over. In 1930 the prize was his. Priya Satia in Aeon:

Priya Satia in Aeon: