by Emrys Westacott

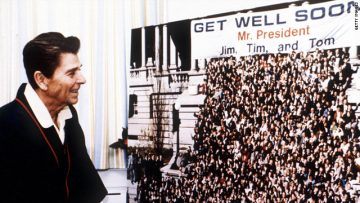

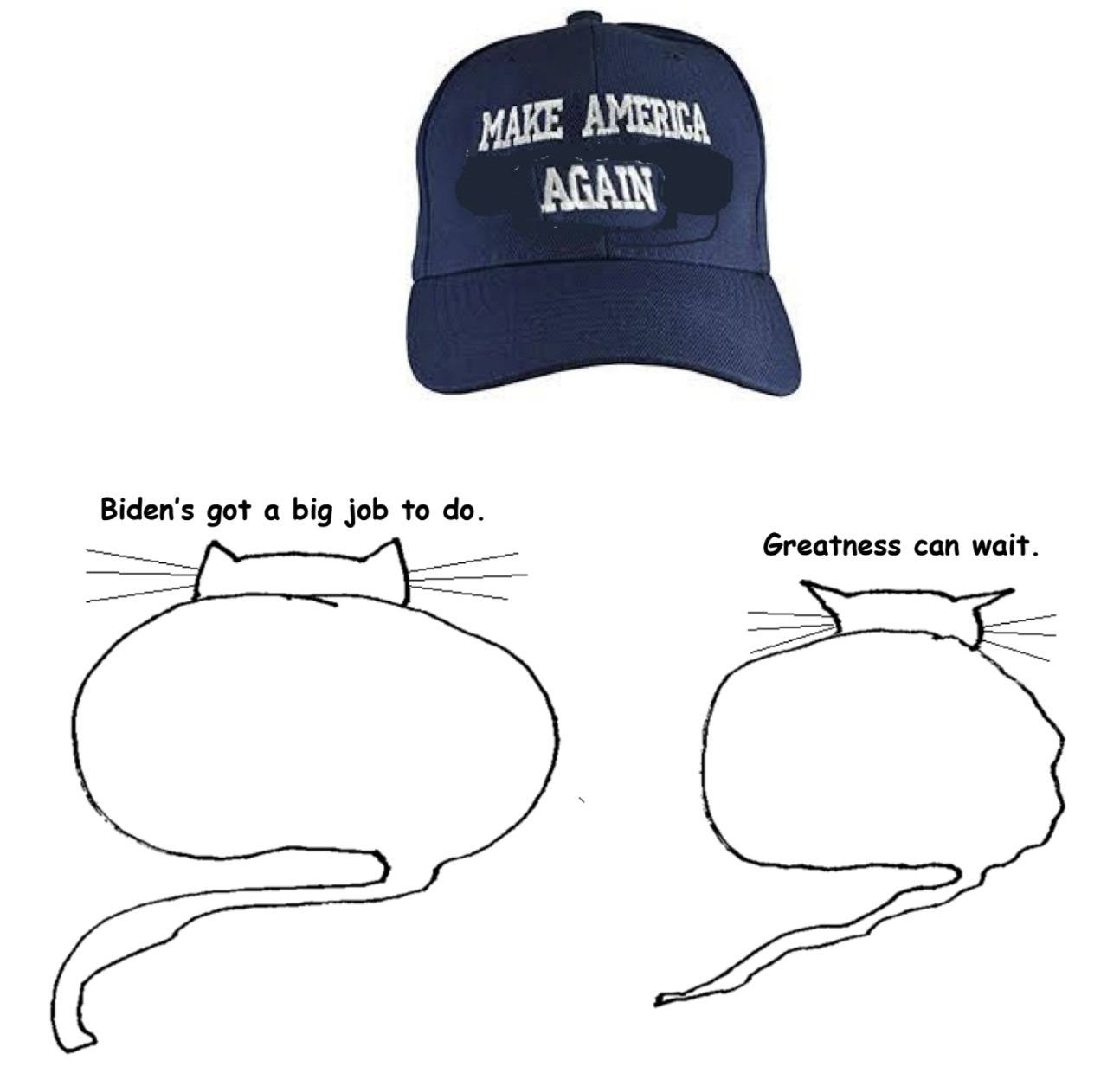

Like millions of others, my reaction to the result of the US presidential election was primarily relief. Relief at the prospect of an end to the ghastly display of narcissism, dishonesty, callousness, corruption, and general moral indecency (a.k.a. Donald Trump) that has dominated media attention in the US for the past four years. Also, relief that American democracy, very imperfect though it is, appears to be coming off the ventilator after what many consider a near death experience. The reaction of Trump and the Republicans, trying every conceivable gambit to thwart the will of the people, indicates just how uninterested they are in upholding democratic norms and how contentious things would have become had everything hinged on the outcome in one state, as it did in the 2000 election.

Like millions of others, my reaction to the result of the US presidential election was primarily relief. Relief at the prospect of an end to the ghastly display of narcissism, dishonesty, callousness, corruption, and general moral indecency (a.k.a. Donald Trump) that has dominated media attention in the US for the past four years. Also, relief that American democracy, very imperfect though it is, appears to be coming off the ventilator after what many consider a near death experience. The reaction of Trump and the Republicans, trying every conceivable gambit to thwart the will of the people, indicates just how uninterested they are in upholding democratic norms and how contentious things would have become had everything hinged on the outcome in one state, as it did in the 2000 election.

And let’s be honest: Biden’s electoral college victory was frighteningly close. He won Pennsylvania by 0.7%, Wisconsin by 0.4%,a and Georgia by 0.3%. Had fewer than 0.5 % of Biden voters gone for Trump in these three states, he would have been re-elected. Moreover, in each of these states the votes received by the Libertarian candidate was greater than Biden’s margin of victory. Who knows how things might have gone had there been no Libertarian candidate.

And let’s keep being honest. But for the covid pandemic, Trump would quite likely have won. Indeed, had he been a more intelligent populist demagogue he might have raised his popularity prior to the election by embracing the role of national champion leading the fight against the virus.

So, like millions of others, after breathing a few sighs of relief and drinking a few celebratory toasts, I find myself asking: How is it possible? Why did over 70 million people vote for a man who to so many of us appears quite obviously to be a pathologically self-centered con man who is callously indifferent to the well-being of others, and who spews an almost continuous stream of barefaced and often quite absurd lies. And I charitably forbear from mentioning his ignorance, his incompetence, his laziness, his bigotry, his sexism, his bullying, his corrupt dealings… Read more »

Emotions are at the same time utterly central to who we are — where would we be without them? — and also seemingly peripheral to the “real” work our brains do, understanding the world and acting within it. Why do we have emotions, anyway? Are they hardwired into the brain? Lisa Feldman Barrett is one of the world’s leading experts in the psychology of emotions, and she emphasizes that they are more constructed and less hard-wired than you might think. How we feel and express emotions can vary from culture to culture or even person to person. It’s better to think of emotions of a link between affective response and our behaviors.

Emotions are at the same time utterly central to who we are — where would we be without them? — and also seemingly peripheral to the “real” work our brains do, understanding the world and acting within it. Why do we have emotions, anyway? Are they hardwired into the brain? Lisa Feldman Barrett is one of the world’s leading experts in the psychology of emotions, and she emphasizes that they are more constructed and less hard-wired than you might think. How we feel and express emotions can vary from culture to culture or even person to person. It’s better to think of emotions of a link between affective response and our behaviors.

ERDAL ARIKAN was

ERDAL ARIKAN was If some of the many thousands of human volunteers needed to test coronavirus vaccines could have been replaced by digital replicas—one of this year’s Top 10 Emerging Technologies—COVID-19 vaccines might have been developed even faster, saving untold lives. Soon virtual clinical trials could be a reality for testing new vaccines and therapies. Other technologies on the list could reduce greenhouse gas emissions by electrifying air travel and enabling sunlight to directly power the production of industrial chemicals. With “spatial” computing, the digital and physical worlds will be integrated in ways that go beyond the feats of virtual reality. And ultrasensitive sensors that exploit quantum processes will set the stage for such applications as wearable brain scanners and vehicles that can see around corners.

If some of the many thousands of human volunteers needed to test coronavirus vaccines could have been replaced by digital replicas—one of this year’s Top 10 Emerging Technologies—COVID-19 vaccines might have been developed even faster, saving untold lives. Soon virtual clinical trials could be a reality for testing new vaccines and therapies. Other technologies on the list could reduce greenhouse gas emissions by electrifying air travel and enabling sunlight to directly power the production of industrial chemicals. With “spatial” computing, the digital and physical worlds will be integrated in ways that go beyond the feats of virtual reality. And ultrasensitive sensors that exploit quantum processes will set the stage for such applications as wearable brain scanners and vehicles that can see around corners. We remember and we forget. Lots of people know that marijuana makes us forget, and researchers in the sixties and seventies wanted to understand how. They discovered that the human brain has special receptors that perfectly fit psychoactive chemicals like THC, the active agent in cannabis. But why, they wondered, would we have neuroreceptors for a foreign substance? We don’t. Those receptors are for substances produced in our own brains. The researchers discovered that we produce cannabinoids, our own version of THC, that fit those receptors exactly. The scientists had stumbled onto the neurochemical function of forgetting, never before understood. We are designed, they realized, not only to remember but also to forget. The first of the neurotransmitters discovered was named anandamide, Sanskrit for bliss.

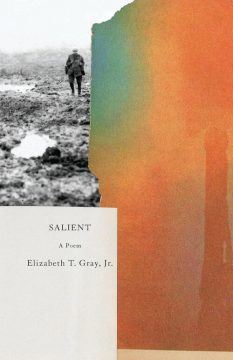

We remember and we forget. Lots of people know that marijuana makes us forget, and researchers in the sixties and seventies wanted to understand how. They discovered that the human brain has special receptors that perfectly fit psychoactive chemicals like THC, the active agent in cannabis. But why, they wondered, would we have neuroreceptors for a foreign substance? We don’t. Those receptors are for substances produced in our own brains. The researchers discovered that we produce cannabinoids, our own version of THC, that fit those receptors exactly. The scientists had stumbled onto the neurochemical function of forgetting, never before understood. We are designed, they realized, not only to remember but also to forget. The first of the neurotransmitters discovered was named anandamide, Sanskrit for bliss. Elizabeth T. Gray, Jr., would seem to write discrete lyrics but no reader gets far in her work without succumbing to an overwhelming sense that a quest is relentlessly underway. It’s a quest that can only be fathomed through a total immersion in history and landscape and immediate psychic needs of those en route: kids out for a journey to the east, soldiers heading into death, the somewhat hidden but ever present presiding consciousness of her two long poems, Series India and Salient, the poet herself as a pained and adamant devotee to some ancient faith on a pilgrimage to the edge of the abyss. The immersion is at times so deep that we might doubt the existence of the wisdom that the figures in her poems are in search of and that the poet herself feels an unassuageable need for, and yet the force of the imagination brought to bear on this imperative for transcendence, and the acute mastery of cadence, phrasing, and image, make us want it too: to see the other side of death, to feel within ourselves some ecstatic completion.

Elizabeth T. Gray, Jr., would seem to write discrete lyrics but no reader gets far in her work without succumbing to an overwhelming sense that a quest is relentlessly underway. It’s a quest that can only be fathomed through a total immersion in history and landscape and immediate psychic needs of those en route: kids out for a journey to the east, soldiers heading into death, the somewhat hidden but ever present presiding consciousness of her two long poems, Series India and Salient, the poet herself as a pained and adamant devotee to some ancient faith on a pilgrimage to the edge of the abyss. The immersion is at times so deep that we might doubt the existence of the wisdom that the figures in her poems are in search of and that the poet herself feels an unassuageable need for, and yet the force of the imagination brought to bear on this imperative for transcendence, and the acute mastery of cadence, phrasing, and image, make us want it too: to see the other side of death, to feel within ourselves some ecstatic completion. From his iconic “Deathfugue,” one of the first poems published about the

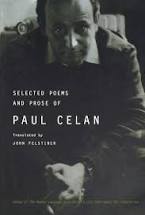

From his iconic “Deathfugue,” one of the first poems published about the  Like millions of others, my reaction to the result of the US presidential election was primarily relief. Relief at the prospect of an end to the ghastly display of narcissism, dishonesty, callousness, corruption, and general moral indecency (a.k.a. Donald Trump) that has dominated media attention in the US for the past four years. Also, relief that American democracy, very imperfect though it is, appears to be coming off the ventilator after what many consider a near death experience. The reaction of Trump and the Republicans, trying every conceivable gambit to thwart the will of the people, indicates just how uninterested they are in upholding democratic norms and how contentious things would have become had everything hinged on the outcome in one state, as it did in the 2000 election.

Like millions of others, my reaction to the result of the US presidential election was primarily relief. Relief at the prospect of an end to the ghastly display of narcissism, dishonesty, callousness, corruption, and general moral indecency (a.k.a. Donald Trump) that has dominated media attention in the US for the past four years. Also, relief that American democracy, very imperfect though it is, appears to be coming off the ventilator after what many consider a near death experience. The reaction of Trump and the Republicans, trying every conceivable gambit to thwart the will of the people, indicates just how uninterested they are in upholding democratic norms and how contentious things would have become had everything hinged on the outcome in one state, as it did in the 2000 election. The United States is undergoing a long-overdue reckoning, in the highest echelons of government, with the problem of systemic racism. The new Biden-Harris administration has

The United States is undergoing a long-overdue reckoning, in the highest echelons of government, with the problem of systemic racism. The new Biden-Harris administration has

1.

1.