Jill Lepore in The New Yorker:

Donald Trump is not much of a note-taker, and he does not like his staff to take notes. He has a habit of tearing up documents at the close of meetings. (Records analysts, armed with Scotch Tape, have tried to put the pieces back together.) No real record exists for five meetings Trump had with Vladimir Putin during the first two years of his Presidency. Members of his staff have routinely used apps that automatically erase text messages, and Trump often deletes his own tweets, notwithstanding a warning from the National Archives and Records Administration that doing so contravenes the Presidential Records Act.

Donald Trump is not much of a note-taker, and he does not like his staff to take notes. He has a habit of tearing up documents at the close of meetings. (Records analysts, armed with Scotch Tape, have tried to put the pieces back together.) No real record exists for five meetings Trump had with Vladimir Putin during the first two years of his Presidency. Members of his staff have routinely used apps that automatically erase text messages, and Trump often deletes his own tweets, notwithstanding a warning from the National Archives and Records Administration that doing so contravenes the Presidential Records Act.

Trump cannot abide documentation for fear of disclosure, and cannot abide disclosure for fear of disparagement. For decades, in private life, he required people who worked with him, and with the Trump Organization, to sign nondisclosure agreements, pledging never to say a bad word about him, his family, or his businesses. He also extracted nondisclosure agreements from women with whom he had or is alleged to have had sex, including both of his ex-wives. In 2015 and 2016, he required these contracts from people involved in his campaign, including a distributor of his “Make America Great Again” hats. (Hillary Clinton’s 2016 campaign required N.D.A.s from some employees, too. In 2020, Joe Biden called on Michael Bloomberg to release his former employees from such agreements.) In 2017, Trump, unable to distinguish between private life and public service, carried his practice of requiring nondisclosure agreements into the Presidency, demanding that senior White House staff sign N.D.A.s. According to the Washington Post, at least one of them, in draft form, included this language: “I understand that the United States Government or, upon completion of the term(s) of Mr. Donald J. Trump, an authorized representative of Mr. Trump, may seek any remedy available to enforce this Agreement including, but not limited to, application for a court order prohibiting disclosure of information in breach of this Agreement.” Aides warned him that, for White House employees, such agreements are likely not legally enforceable. The White House counsel, Don McGahn, refused to distribute them; eventually, he relented, and the chief of staff, Reince Priebus, pressured employees to sign them.

More here.

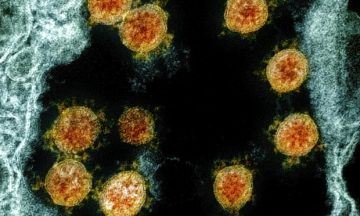

Letting the virus that causes Covid-19 circulate more-or-less freely is dangerous not only because it risks overwhelming hospitals and so endangering lives unnecessarily, but also because it could delay the evolution of the virus to a more benign form and potentially even make it more lethal.

Letting the virus that causes Covid-19 circulate more-or-less freely is dangerous not only because it risks overwhelming hospitals and so endangering lives unnecessarily, but also because it could delay the evolution of the virus to a more benign form and potentially even make it more lethal.

As picks for President-elect Joe Biden’s Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) transition team were announced, I felt concerned and disheartened about

As picks for President-elect Joe Biden’s Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) transition team were announced, I felt concerned and disheartened about A team of researchers from multiple departments at Stanford University has created a cellular atlas of the human lung that highlights the dozens of cell types that comprise parts of the lungs. In their paper published in the journal Nature, the researchers describe their work (mostly involving single-cell RNA sequencing) and some of the things they learned about the lungs during their effort. To create the atlas, the researchers collected

A team of researchers from multiple departments at Stanford University has created a cellular atlas of the human lung that highlights the dozens of cell types that comprise parts of the lungs. In their paper published in the journal Nature, the researchers describe their work (mostly involving single-cell RNA sequencing) and some of the things they learned about the lungs during their effort. To create the atlas, the researchers collected  Donald Trump is not much of a note-taker, and he does not like his staff to take notes. He has a habit of tearing up documents at the close of meetings. (Records analysts, armed with Scotch Tape, have tried to put the pieces back together.) No real record exists for five meetings Trump had with Vladimir Putin during the first two years of his Presidency. Members of his staff have routinely used apps that automatically erase text messages, and Trump often deletes his own tweets, notwithstanding a warning from the National Archives and Records Administration that doing so contravenes the Presidential Records Act.

Donald Trump is not much of a note-taker, and he does not like his staff to take notes. He has a habit of tearing up documents at the close of meetings. (Records analysts, armed with Scotch Tape, have tried to put the pieces back together.) No real record exists for five meetings Trump had with Vladimir Putin during the first two years of his Presidency. Members of his staff have routinely used apps that automatically erase text messages, and Trump often deletes his own tweets, notwithstanding a warning from the National Archives and Records Administration that doing so contravenes the Presidential Records Act. James never stopped short in an exploration or an argument—and for him that meant never stopping short of the biggest question: the religious one. His thinking of the late 1890s kept pushing in this direction, culminating in the Gifford Lectures delivered in Edinburgh in 1901 and 1902, the lectures known to posterity as The Varieties of Religious Experience. James felt that the question of this world and the other world was somehow decisive for all of us, whichever way we answered it. And that included a whole lot of answers for someone like William James—attender of séances, consulter of mediums and all-around junkie for experience. In “The Will to Believe,” James is mostly interested in leveling the playing field vis-à-vis his skeptical colleagues. When it comes down to it, he wonders, why can’t we just go ahead and will the belief in God? The stern-minded skeptic is happy to object: we have no evidence for it. James replies: we have no evidence against it. The skeptic concedes, and objects again: well, then, I’ll wait until we have decisive evidence one way or the other. William James: to spend a life in indecision is no different from choosing against it; for example, if you have no decisive evidence that a potential career is best for you, you can’t just delay your decision until you die. The skeptic: but religion is not like that. William James: why not?

James never stopped short in an exploration or an argument—and for him that meant never stopping short of the biggest question: the religious one. His thinking of the late 1890s kept pushing in this direction, culminating in the Gifford Lectures delivered in Edinburgh in 1901 and 1902, the lectures known to posterity as The Varieties of Religious Experience. James felt that the question of this world and the other world was somehow decisive for all of us, whichever way we answered it. And that included a whole lot of answers for someone like William James—attender of séances, consulter of mediums and all-around junkie for experience. In “The Will to Believe,” James is mostly interested in leveling the playing field vis-à-vis his skeptical colleagues. When it comes down to it, he wonders, why can’t we just go ahead and will the belief in God? The stern-minded skeptic is happy to object: we have no evidence for it. James replies: we have no evidence against it. The skeptic concedes, and objects again: well, then, I’ll wait until we have decisive evidence one way or the other. William James: to spend a life in indecision is no different from choosing against it; for example, if you have no decisive evidence that a potential career is best for you, you can’t just delay your decision until you die. The skeptic: but religion is not like that. William James: why not? No one is going to base a claim for Bloom’s merits on this final book. But it does indicate, with painful acuity, that the critic may have had little understanding of how literature is made — which is not out of ideas, as Mallarmé patiently explained to Cézanne. It doesn’t achieve its effects by saying ‘this is funny’ or ‘this is so moving’. It relishes its own voice — and to dwell on what it has stolen from others misses its ambition.

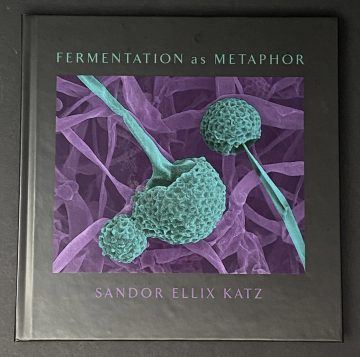

No one is going to base a claim for Bloom’s merits on this final book. But it does indicate, with painful acuity, that the critic may have had little understanding of how literature is made — which is not out of ideas, as Mallarmé patiently explained to Cézanne. It doesn’t achieve its effects by saying ‘this is funny’ or ‘this is so moving’. It relishes its own voice — and to dwell on what it has stolen from others misses its ambition. Sandor Katz: Well, sure. The reason I started calling myself a fermentation revivalist is from my sense of how common fermentation has been in the not too distant past and it’s so integral to all of our food traditions. Whatever part of the world our ancestors came from, fermentation is an essential part of how people make effective use of whatever food resources are available to them, but in the last several generations and at different paces in different parts of the world, people have become increasingly distanced from the production of food and all of the processes that we use to transform the raw products of agriculture into all of the foods that people eat and drink. And it so happens that the same time period where these processes became more mysterious and distanced to people is also the time when the war on bacteria developed. People developed this fear, projected all of their fear of bacteria onto these ancient and important transformative fermentation processes. So when I call myself a fermentation revivalist, it’s about demystifying the process of fermentation, getting people comfortable with it, and encouraging people to familiarize themselves with processes that are extremely important but have become mysterious for people.

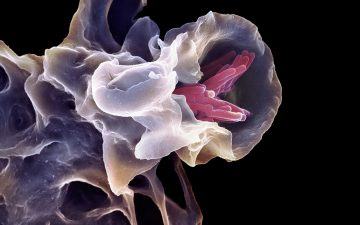

Sandor Katz: Well, sure. The reason I started calling myself a fermentation revivalist is from my sense of how common fermentation has been in the not too distant past and it’s so integral to all of our food traditions. Whatever part of the world our ancestors came from, fermentation is an essential part of how people make effective use of whatever food resources are available to them, but in the last several generations and at different paces in different parts of the world, people have become increasingly distanced from the production of food and all of the processes that we use to transform the raw products of agriculture into all of the foods that people eat and drink. And it so happens that the same time period where these processes became more mysterious and distanced to people is also the time when the war on bacteria developed. People developed this fear, projected all of their fear of bacteria onto these ancient and important transformative fermentation processes. So when I call myself a fermentation revivalist, it’s about demystifying the process of fermentation, getting people comfortable with it, and encouraging people to familiarize themselves with processes that are extremely important but have become mysterious for people. Animal immune systems depend on white blood cells called macrophages that devour and engulf invaders. The cells pursue with determination and gusto: under a microscope you can watch a blob-like macrophage chase a bacterium across the slide, switching course this way and that as its prey tries to escape through an obstacle course of red blood cells, before it finally catches the rogue microbe and gobbles it up.

Animal immune systems depend on white blood cells called macrophages that devour and engulf invaders. The cells pursue with determination and gusto: under a microscope you can watch a blob-like macrophage chase a bacterium across the slide, switching course this way and that as its prey tries to escape through an obstacle course of red blood cells, before it finally catches the rogue microbe and gobbles it up. The current debates over cancel culture are odd because few involved in them have been canceled, or risk being canceled, while entire institutions are indeed being canceled. Institutions that serve and amplify the interests of the working class, such as local newspapers, unions, and churches.

The current debates over cancel culture are odd because few involved in them have been canceled, or risk being canceled, while entire institutions are indeed being canceled. Institutions that serve and amplify the interests of the working class, such as local newspapers, unions, and churches. “There is only one school,” Amis has said, “that of talent.” Only the talented would ever think this, and only the supremely talented would ever say it out loud. Inside Story is subtitled How to Write. But Amis has been telling us how to write for half a century now, and not just in his criticism. The virtuoso is always also a pedagogue. Look – this is how you do it! And the feudal lord – the seigneur – is, by definition, an aristocrat (and, not incidentally, by definition male): “rangy, well-travelled, big-cocked”, in the mocking, but also not-quite-mocking, words of Charles Highway in The Rachel Papers (1973). When Amis fails, this seigneurialism is what he’s left with: all those epigrams! All those cringey jokes! That tone of sneering condescension! (See Yellow Dog, The Pregnant Widow, Lionel Asbo. Seigneurialism – anathematised as “male privilege” – is what feminist critics have tended to find so rebarbative in Amis’s work, and they’re not wrong.) When he succeeds, the seigneurialism is merely part of the effect (see Money, London Fields, Time’s Arrow, almost all of the nonfiction).

“There is only one school,” Amis has said, “that of talent.” Only the talented would ever think this, and only the supremely talented would ever say it out loud. Inside Story is subtitled How to Write. But Amis has been telling us how to write for half a century now, and not just in his criticism. The virtuoso is always also a pedagogue. Look – this is how you do it! And the feudal lord – the seigneur – is, by definition, an aristocrat (and, not incidentally, by definition male): “rangy, well-travelled, big-cocked”, in the mocking, but also not-quite-mocking, words of Charles Highway in The Rachel Papers (1973). When Amis fails, this seigneurialism is what he’s left with: all those epigrams! All those cringey jokes! That tone of sneering condescension! (See Yellow Dog, The Pregnant Widow, Lionel Asbo. Seigneurialism – anathematised as “male privilege” – is what feminist critics have tended to find so rebarbative in Amis’s work, and they’re not wrong.) When he succeeds, the seigneurialism is merely part of the effect (see Money, London Fields, Time’s Arrow, almost all of the nonfiction). The story of Joy Division, and later New Order, is repeated so often it feels more like myth than reality. Maxine Peake’s voice is full of whispered awe as she leads us through a story that begins with three simple words – “Band seeks singer” – and ends with the making of the iconic “Blue Monday”.

The story of Joy Division, and later New Order, is repeated so often it feels more like myth than reality. Maxine Peake’s voice is full of whispered awe as she leads us through a story that begins with three simple words – “Band seeks singer” – and ends with the making of the iconic “Blue Monday”. ISLAMABAD, Pakistan — I am angry. All the time. I’ve been angry for years. Ever since I began to grasp the staggering extent of violence — emotional, mental and physical — against women in Pakistan. Women here, all 100 million of us, exist in collective fury. “Every day, I am reminded of a reason I shouldn’t exist,” my 19-year-old friend recently told me in a cafe in Islamabad. When she gets into an Uber, she sits right behind the driver so that he can’t reach back and grab her. We agreed that we would jump out of a moving car if that ever happened. We debated whether pepper spray was better than a knife. When I step outside, I step into a country of men who stare. I could be making the short walk from my car to the bookstore or walking through the aisles at the supermarket. I could be wrapped in a shawl or behind two layers of face mask. But I will be followed by searing eyes, X-raying me. Because here, it is culturally acceptable for men to gape at women unblinkingly, as if we are all in a staring contest that nobody told half the population about, a contest hinged on a subtle form of psychological violence.

ISLAMABAD, Pakistan — I am angry. All the time. I’ve been angry for years. Ever since I began to grasp the staggering extent of violence — emotional, mental and physical — against women in Pakistan. Women here, all 100 million of us, exist in collective fury. “Every day, I am reminded of a reason I shouldn’t exist,” my 19-year-old friend recently told me in a cafe in Islamabad. When she gets into an Uber, she sits right behind the driver so that he can’t reach back and grab her. We agreed that we would jump out of a moving car if that ever happened. We debated whether pepper spray was better than a knife. When I step outside, I step into a country of men who stare. I could be making the short walk from my car to the bookstore or walking through the aisles at the supermarket. I could be wrapped in a shawl or behind two layers of face mask. But I will be followed by searing eyes, X-raying me. Because here, it is culturally acceptable for men to gape at women unblinkingly, as if we are all in a staring contest that nobody told half the population about, a contest hinged on a subtle form of psychological violence. Robert Gates’s first memoir was titled “

Robert Gates’s first memoir was titled “ Comedy inverts norms and breaks barriers. But in order to reveal, as Northrop Frye suggested it must, “absurd or irrational [patriarchal] law,” comedy requires a fall guy. There has to be somebody on whom that law can come crashing down, in all its absurdity, all its irrationality—somebody who improbably emerges at the end, unscathed or even triumphant. Buster Keaton, that beautifully deadpan clown known as “The Great Stone Face,” had the pliability—and the subtle anarchic capacity for nonviolent resistance—to fill that role like nobody else before him. Or since.

Comedy inverts norms and breaks barriers. But in order to reveal, as Northrop Frye suggested it must, “absurd or irrational [patriarchal] law,” comedy requires a fall guy. There has to be somebody on whom that law can come crashing down, in all its absurdity, all its irrationality—somebody who improbably emerges at the end, unscathed or even triumphant. Buster Keaton, that beautifully deadpan clown known as “The Great Stone Face,” had the pliability—and the subtle anarchic capacity for nonviolent resistance—to fill that role like nobody else before him. Or since.