by Peter Wells

Well, I’ve looked at David Goodhart’s book (The Road to Somewhere – The New Tribes Shaping British Politics: 2017) and I’m obviously an Anywhere. [All quotes are from the Kindle edition]. “They tend to do well at school [Well, reasonably], then usually move from home to a residential university in their late teens [Yes] and on to a career in the professions [Teaching] that might take them to London or even abroad [Yes, indeed] for a year or two [or eighteen!]. Such people have portable ‘achieved’ identities, based on educational and career success which makes them generally comfortable and confident with new places and people [Generally!].”

Well, I’ve looked at David Goodhart’s book (The Road to Somewhere – The New Tribes Shaping British Politics: 2017) and I’m obviously an Anywhere. [All quotes are from the Kindle edition]. “They tend to do well at school [Well, reasonably], then usually move from home to a residential university in their late teens [Yes] and on to a career in the professions [Teaching] that might take them to London or even abroad [Yes, indeed] for a year or two [or eighteen!]. Such people have portable ‘achieved’ identities, based on educational and career success which makes them generally comfortable and confident with new places and people [Generally!].”

My father was lifted out of the conservative background of his family by several years of residential higher education, had a job which caused us to move every three or four years, and wired the house to broadcast BBC Radio 4 (or its predecessor, the Home Service) to every room. My infant toys included female as well as male dolls, and, what’s more, one of the females was a little black girl! (Don’t be condescending – we’re talking the late 40s!) The first black person I met was an African student on homestay with us, who shed light for me on the mysteries of Latin grammar (I returned the compliment by teaching Latin to Zimbabweans five years later!). (Sorry! I meant well!)

So I pass Goodhart’s worldview test: “This [sc. Anywhereism] is a worldview for more or less successful individuals [Check, though rather less than more!] who also care about society [Check]. It places a high value on autonomy, mobility and novelty [Check] and a much lower value on group identity, tradition and national social contracts (faith, flag and family) [Check]. Most Anywheres are comfortable with immigration, European integration and the spread of human rights legislation [Check]. They … see themselves as citizens of the world [Check 110%!].”

The privileges opened up to me by this certification were immense. Repeatedly during my career I was able to enter the ‘alien’ environments of foreign countries, in Africa, Asia and the Middle East – not as a tourist but as a resident, worker, colleague, neighbour and friend. Seeing how people of a different culture live, think, laugh, learn, befriend, commute, pay, greet, and grieve, enabled me to put my own attitudes and presuppositions into perspective. I realised that what had looked to me like a central and obvious norm was just the point of view that I happened to have been brought up with. My wife and I were offered a glimpse of at least five very distinctive ways to live, instead of the sole option that most people are granted. More than anything else, this is what makes working abroad a joy and delight. The elusive quality of a national culture defies stereotyping. Like the flavour of a loved one’s cooking, it is itself. Africans, Arabs, Japanese are not reducible to epithets: they are what they are. A spouse who has had the same experience will know what you mean when you say, “That’s just like Oman / Malawi / Japan, isn’t it.” Our friends have no idea what we are talking about! You can, of course, obtain a similar experience by visiting a different part of your own country, or even someone else’s house, but for the full culture shock you need to change countries! Read more »

One of the strangest books to come out of Europe in the sixteenth century – and that is saying a lot – is John Dee’s

One of the strangest books to come out of Europe in the sixteenth century – and that is saying a lot – is John Dee’s

Michele Morano’s first collection of essays, Grammar Lessons: Translating a Life in Spain, is a classic of travel literature that I have taught several times, to the great pleasure of over a decade’s worth of students. Now she has bested the power of that excellent book with a new collection of essays,

Michele Morano’s first collection of essays, Grammar Lessons: Translating a Life in Spain, is a classic of travel literature that I have taught several times, to the great pleasure of over a decade’s worth of students. Now she has bested the power of that excellent book with a new collection of essays,

If you go to Kashmir today this is what you will see. As you drive away from Srinagar’s Hum Hama airport, a large green billboard with white lettering proclaims, Welcome to Paradise.

If you go to Kashmir today this is what you will see. As you drive away from Srinagar’s Hum Hama airport, a large green billboard with white lettering proclaims, Welcome to Paradise. Conspiracy theories come in all shapes and sizes, but perhaps the most common form is the Global Cabal theory. A

Conspiracy theories come in all shapes and sizes, but perhaps the most common form is the Global Cabal theory. A  On a mild autumn day in 2016, the Hungarian mathematician

On a mild autumn day in 2016, the Hungarian mathematician  Concern about American democracy is often expressed as a parable of the Thirties: We must prevent another Hitler. The word “fascism” has appeared frequently in denunciations of Donald Trump; many have accused him of a führer-like contempt for the American system. But it is time to ask whether the system itself is not thereby too conveniently excused. Mass political participation has come only recently and reluctantly to America; voter suppression is the more traditional American way. And for reasons that have nothing to do with fascism, even that partial efflorescence may be coming to an end. Trump’s baleful theatrics have distracted us, in fact, from the broader disintegration of the twentieth-century interregnum, of which he is only a symptom. That process has much further to go, and will produce dangers greater than he.

Concern about American democracy is often expressed as a parable of the Thirties: We must prevent another Hitler. The word “fascism” has appeared frequently in denunciations of Donald Trump; many have accused him of a führer-like contempt for the American system. But it is time to ask whether the system itself is not thereby too conveniently excused. Mass political participation has come only recently and reluctantly to America; voter suppression is the more traditional American way. And for reasons that have nothing to do with fascism, even that partial efflorescence may be coming to an end. Trump’s baleful theatrics have distracted us, in fact, from the broader disintegration of the twentieth-century interregnum, of which he is only a symptom. That process has much further to go, and will produce dangers greater than he.

Individual poems by Vilariño have occasionally appeared in anthologies of Latin American poetry in the United States, but not until now, more than a decade after her death and in the centennial year of her birth, has one of her books appeared in English translation. Unsurprisingly, it is her best-known work, Poemas de amor / Love Poems (University of Pittsburgh Press, 2020), in a translation by the poet Jesse Lee Kercheval. The literary scholar Emir Rodríguez Monegal, a Yale professor who wrote influential treatises on

Individual poems by Vilariño have occasionally appeared in anthologies of Latin American poetry in the United States, but not until now, more than a decade after her death and in the centennial year of her birth, has one of her books appeared in English translation. Unsurprisingly, it is her best-known work, Poemas de amor / Love Poems (University of Pittsburgh Press, 2020), in a translation by the poet Jesse Lee Kercheval. The literary scholar Emir Rodríguez Monegal, a Yale professor who wrote influential treatises on  Similar to Tony Conrad—who reflected in one of his

Similar to Tony Conrad—who reflected in one of his  There are more than 120 biobanks worldwide, having evolved over the past 30 years. They range from small, predominantly university-based repositories, to large, government-supported resources. As well as collecting and storing samples, they also provide clinical, pathological, molecular and radiological information for research into personalized medicine. Biobanks allow researchers to explore the causes of disease by helping them link genotypes to phenotypes. This is a process that has been underway for years through genome-wide association studies (GWAS), but it has proved far from straightforward. “What we have learned from GWAS over the last 15 to 20 years is that there are many variants, they have small effect sizes and, even if you total most of the common variants throughout the genome, they account for only a small fraction of phenotypic variance,” says Judy Cho, a translational geneticist at Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York.

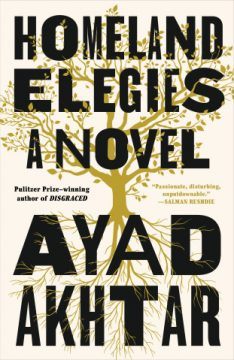

There are more than 120 biobanks worldwide, having evolved over the past 30 years. They range from small, predominantly university-based repositories, to large, government-supported resources. As well as collecting and storing samples, they also provide clinical, pathological, molecular and radiological information for research into personalized medicine. Biobanks allow researchers to explore the causes of disease by helping them link genotypes to phenotypes. This is a process that has been underway for years through genome-wide association studies (GWAS), but it has proved far from straightforward. “What we have learned from GWAS over the last 15 to 20 years is that there are many variants, they have small effect sizes and, even if you total most of the common variants throughout the genome, they account for only a small fraction of phenotypic variance,” says Judy Cho, a translational geneticist at Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York. IF YOU’VE ALREADY READ Camus’s The Plague and have been searching for the perfect pre-apocalyptic fiction work to help you navigate our current affairs, this book may be just the provocation. I opened it knowing little about the author, other than having seen him act in the independent feature The War Within and perused his play Disgraced. Neither had prepared me for Homeland Elegies, which turns out to be masterful storytelling for these disturbing times.

IF YOU’VE ALREADY READ Camus’s The Plague and have been searching for the perfect pre-apocalyptic fiction work to help you navigate our current affairs, this book may be just the provocation. I opened it knowing little about the author, other than having seen him act in the independent feature The War Within and perused his play Disgraced. Neither had prepared me for Homeland Elegies, which turns out to be masterful storytelling for these disturbing times.