by Jonathan Kujawa

“Odd,” agreed Reg. “I’ve certainly never come across any irreversible mathematics involving sofas. Could be a new field. Have you spoken to any spatial geometricians?” —Douglas Adams, “Dirk Gently’s Holistic Detective Agency”

It turns out mathematicians are well-adapted to working from home in the covid-19 pandemic. We don’t need research labs or access to original texts for our research, and teaching math over video chat is infinitely easier than art, music, literature, foreign languages, or practically any other subject. That said, mathematicians get cabin fever, too.

Recently, Anne and I have been talking about rearranging our offices here at home. In the past, they doubled as guest bedrooms and storage for exercise equipment and homeless plants. Which is fine if you’re using them for weekend afternoons and the occasional work-from-home day. But it’s six months in and time for our house to better match the present and foreseeable future.

Our first idea was to replace a guest bed in one office with a couch. Setting aside the difficulty of choosing a new couch sight unseen during a pandemic, there was the more practical problem of choosing one which could actually fit into our house. Read more »

I’ve been airborne since

I’ve been airborne since

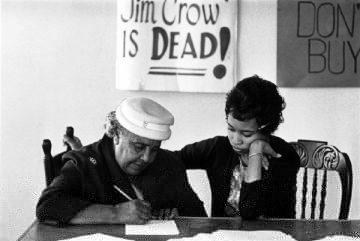

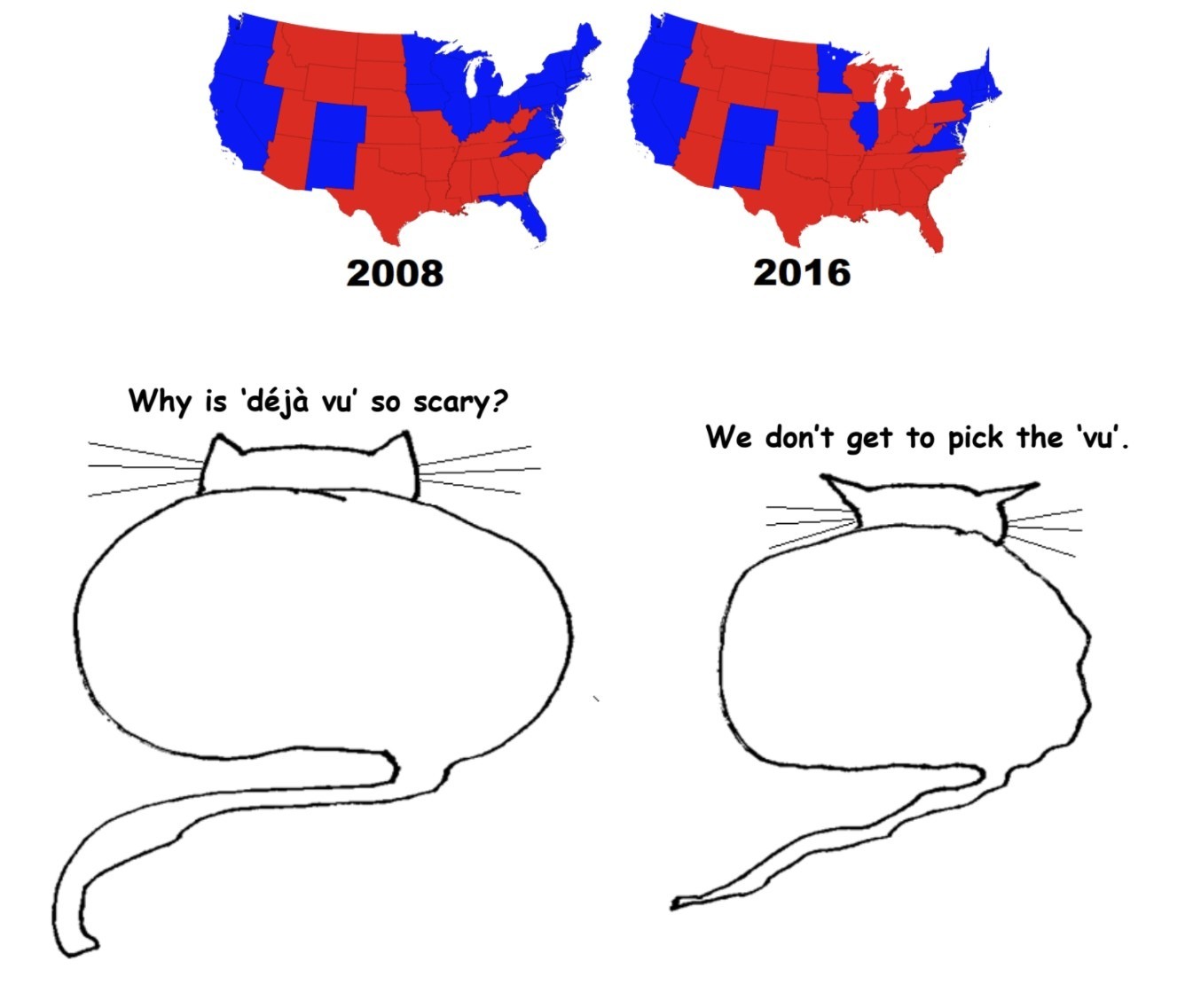

In the presidential election of 2016, around 45% of adult eligible to vote in the USA did not vote. It isn’t disputed that voter suppression, disproportionately affecting people of colour, was one of the causes. Another seems to be a cynicism, or apathy about the process itself. And there may be other reasons. But however you look at it, a situation in which nearly half of the eligible population doesn’t vote in an election for the highest office in the land ought to be causing a good deal of alarm, and not just for those political actors who reckon to be most damaged by this blank statistic. But then, ‘democracy’ has always been rather more of an unfulfilled promise than an accomplished fact, even in the Land of the Free (as well as in the land that boasts the ‘Mother of Parliaments’, where I live).

In the presidential election of 2016, around 45% of adult eligible to vote in the USA did not vote. It isn’t disputed that voter suppression, disproportionately affecting people of colour, was one of the causes. Another seems to be a cynicism, or apathy about the process itself. And there may be other reasons. But however you look at it, a situation in which nearly half of the eligible population doesn’t vote in an election for the highest office in the land ought to be causing a good deal of alarm, and not just for those political actors who reckon to be most damaged by this blank statistic. But then, ‘democracy’ has always been rather more of an unfulfilled promise than an accomplished fact, even in the Land of the Free (as well as in the land that boasts the ‘Mother of Parliaments’, where I live).

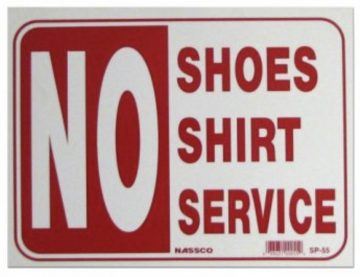

When I was a kid, I used to see this little sign everywhere (still see it occasionally): “No shoes. No shirt. No service.” It was on the door of every store, including the store down at the gas station. It used to make me laugh for some reason. Maybe, just the image of this shoeless, shirtless madman storming the store for more toilet paper.

When I was a kid, I used to see this little sign everywhere (still see it occasionally): “No shoes. No shirt. No service.” It was on the door of every store, including the store down at the gas station. It used to make me laugh for some reason. Maybe, just the image of this shoeless, shirtless madman storming the store for more toilet paper.

COUNTERFACTUALS TEND TO BE more intriguing when they bend sinister. They reassure us that our times aren’t as bad as they might have been, but warn us about where we could still end up. What if xenophobic Charles Lindbergh had been elected president in 1940, as in Philip Roth’s The Plot Against America, or if the Axis powers had prevailed in World War II, as in Philip K. Dick’s The Man in the High Castle? Would it be worth, however, indulging a less theatrical alternative history: what if Vice President Henry A. Wallace had been re-nominated as Franklin D. Roosevelt’s running mate in 1944 rather than being replaced by Harry Truman?

COUNTERFACTUALS TEND TO BE more intriguing when they bend sinister. They reassure us that our times aren’t as bad as they might have been, but warn us about where we could still end up. What if xenophobic Charles Lindbergh had been elected president in 1940, as in Philip Roth’s The Plot Against America, or if the Axis powers had prevailed in World War II, as in Philip K. Dick’s The Man in the High Castle? Would it be worth, however, indulging a less theatrical alternative history: what if Vice President Henry A. Wallace had been re-nominated as Franklin D. Roosevelt’s running mate in 1944 rather than being replaced by Harry Truman? Unless you’re a physicist or an engineer, there really isn’t much reason for you to know about partial differential equations. I know. After years of poring over them in undergrad while studying mechanical engineering, I’ve never used them since in the real world.

Unless you’re a physicist or an engineer, there really isn’t much reason for you to know about partial differential equations. I know. After years of poring over them in undergrad while studying mechanical engineering, I’ve never used them since in the real world. Suppose you believe the state should look after the wellbeing of the poor and combat the structural forces that enrich the wealthy. Suppose you’re in a two-party electoral system, and that the party notionally aligned with your ideals made a Faustian pact with business elites to shore up the policies that perpetuate poverty – low minimum wages, tax incentives for rent-seekers, privatisation of public services, etc. What kind of ballot should you cast? You can’t vote for the party pushing things further to the Right. And if you don’t vote, or you vote for someone who’s almost certain not to win, you’re helping that same regressive party get elected. Yet lending your support to the ‘lesser of two evils’ candidate, whose platform you don’t really support, feels like an unacceptable compromise to your ideals.

Suppose you believe the state should look after the wellbeing of the poor and combat the structural forces that enrich the wealthy. Suppose you’re in a two-party electoral system, and that the party notionally aligned with your ideals made a Faustian pact with business elites to shore up the policies that perpetuate poverty – low minimum wages, tax incentives for rent-seekers, privatisation of public services, etc. What kind of ballot should you cast? You can’t vote for the party pushing things further to the Right. And if you don’t vote, or you vote for someone who’s almost certain not to win, you’re helping that same regressive party get elected. Yet lending your support to the ‘lesser of two evils’ candidate, whose platform you don’t really support, feels like an unacceptable compromise to your ideals. The camera costs $58,990, including a 70mm lens made by Phase One partner Rodenstock. If you want the 23mm, 32mm or 50mm lenses, expect to pony up another $11,990 each. A

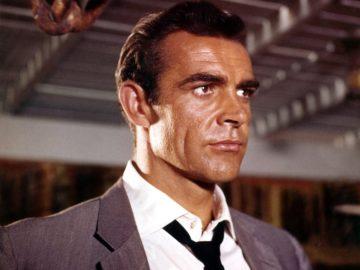

The camera costs $58,990, including a 70mm lens made by Phase One partner Rodenstock. If you want the 23mm, 32mm or 50mm lenses, expect to pony up another $11,990 each. A  Sean Connery

Sean Connery