by Chris Horner

In the presidential election of 2016, around 45% of adult eligible to vote in the USA did not vote. It isn’t disputed that voter suppression, disproportionately affecting people of colour, was one of the causes. Another seems to be a cynicism, or apathy about the process itself. And there may be other reasons. But however you look at it, a situation in which nearly half of the eligible population doesn’t vote in an election for the highest office in the land ought to be causing a good deal of alarm, and not just for those political actors who reckon to be most damaged by this blank statistic. But then, ‘democracy’ has always been rather more of an unfulfilled promise than an accomplished fact, even in the Land of the Free (as well as in the land that boasts the ‘Mother of Parliaments’, where I live).

In the presidential election of 2016, around 45% of adult eligible to vote in the USA did not vote. It isn’t disputed that voter suppression, disproportionately affecting people of colour, was one of the causes. Another seems to be a cynicism, or apathy about the process itself. And there may be other reasons. But however you look at it, a situation in which nearly half of the eligible population doesn’t vote in an election for the highest office in the land ought to be causing a good deal of alarm, and not just for those political actors who reckon to be most damaged by this blank statistic. But then, ‘democracy’ has always been rather more of an unfulfilled promise than an accomplished fact, even in the Land of the Free (as well as in the land that boasts the ‘Mother of Parliaments’, where I live).

Slow Progress

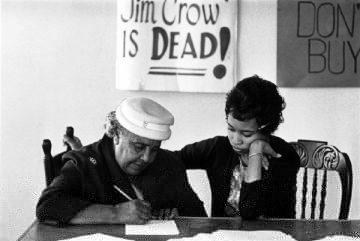

In the years following the independence of the 13 colonies from Britain, voting rights for women and native Americans were only extended very gradually (1920 and 1924 respectively). For African Americans the picture is complicated by the different laws in the states, even after the Emancipation Proclamation. Many non white Americans weren’t actually able to exercise their right to vote in the segregated south well into the middle of the 20th century. Even today, extensive gerrymandering and selective use of felony disbarments as well as ID voting conditions continue to be used to exclude black citizens from expressing their democratic choice at the ballot box. And there remains the misuse of the election ballot and its ‘hanging chads’, as well as the power of the Electoral College to modify inconvenient electoral outcomes. Failing that, there is the similarity between the two main parties to act as a block on radical change. Much of this is well known.

What is less often remarked is that even at independence poor whites couldn’t vote either (Washington was elected on a franchise that only extended to 6% of the population). The franchise was extended to poorer white men during the 19th century (different states had different laws and President Jackson, that killer of native Americans, was pivotal in extending democracy to white men). But from the start it was a designed as a limited democracy, and in many ways it has stayed limited. The idea that the USA was actually founded on the principle of full democratic participation is quite mistaken. It was founded on the notion of limited and constrained democracy. Only pressure from below has partially changed things.

Democracy Deferred

The same process of extending the franchise in stages was also going on in Britain in the 19th century. The USA was ahead of Britain in this respect, but not so far ahead as all that. (The French had been ahead of both in 1793, but voting rights underwent restrictions after the Jacobins fell from power). That the franchise was extended to all adult citizens had a lot to do with pressure, with the struggles, that occurred throughout that period, and beyond. In Britain in 1918 the vote was extended to all men over 21, and to women over the age of 30 who were householders, the wives of householders, occupiers of property with an annual rent of £5, and graduates of British universities. The franchise was only extended to all women over 21 in 1928. In Northern Ireland voting in local elections was still connected to being a householder until the late 1960s. Widening the franchise was the result of decades of struggle in both countries – by Chartists, Suffragettes, the Civil Rights movement and more. None of it was simply accepted as a matter of course. ‘Power concedes nothing without a demand. It never did and it never will’ as Frederick Douglass famously remarked. Neither the USA or the UK has ever had simple commitment to the practice, as distinct from the rhetoric of democracy, and that remains true today.

Which prompts this thought about the USA on the eve of the 2020 Presidential Election: the founding of the USA is more important in terms of its promise – the principle of political equality – rather than the fact. We are still waiting for that promise to be made good, not just in the USA but across the ‘democratic’ world. And one might add that political democracy is itself a rather limited thing. How much democracy is there, after all, in the workplace? Democracy itself is an extremely marginal thing for most people. The opportunity to actually change the way things are run is really quite limited, and while one should certainly use whatever levers one has to affect government a national and local level, we shouldn’t delude ourselves that ‘rule by the people’ runs very deep in the modern Liberal State. The area in which one’s choices are most promoted is that of consumer sovereignty – the opportunity to choose between umpteen types of toothbrush or shampoo.

The Demand

It’s especially moot, given the obsession with the word ‘democracy’ that the USA and the U.K. have. We hear it nearly all the time. The use of the label often acts as a substitute for creative political thought, as if its meaning were clear as day. But it was one of Nietzsche’s insights that the really significant words tend to change their meaning over time, and ‘democracy’ is no exception here. Certainly, it has something to do with rule by the people, but which people? And how? What counts as ‘democratic’ changes over time, as does the reality of who gets included as a voter and who does not.

We should also ask who benefits from widespread cynicism and voter disengagement. Perhaps the nature of our democracies is such that they have been framed to not only limit the popular will in elections, but also to encourage it to go do something else instead of voting. Too often, lack of engagement in elections is treated only as a matter for psephologists, and the questions of how age and occupation affects willingness to vote. All that has its place, of course, but it shouldn’t obscure the truth that low voter engagement is itself a political matter, connected to the desire of the well off and powerful to retain their dominance undisturbed by the Demos. Political disengagement and voter suppression disproportionally benefits those who do well out of the current system. Democracy, so far, has been marked by its limited and often exclusionary nature, denied, blocked and subverted by class, racism, patriarchy and ‘the markets’. If we take the view that this is as good as it gets for democracy, we are liable to get more of the same – or even less, if capitalism finds what democracy we do have too irksome to continue to tolerate. It may be, on the other hand, that we don’t yet know what democracy might be. To answer that question, we should recall Douglass’ point about the importance of making a demand. And then make that demand – and vote.