by Thomas Larson

In 1874, Thomas Hardy married Emma Gifford, a woman who never let her novelist husband forget that she was born of a higher class than he, ever his superior in taste and breeding. After her death he got back at her—poetically—in a big way. And she—from the grave—at him.

The pair began a premarital affair, fervent and soulful, as romantic and intellectual companions; not long after, they were quarantined in thirty-eight years of a childless and mutually regrettable marriage. When Emma died of a bad heart and impacted gallstones (she wrote treacly poems, many published, and suffered from delusions of grandeur), Hardy at sixty-two composed a loose sequence of verse, “Poems of 1912-1913.” These twenty-one rhyming, pithy elegies, among the finest in English, conjure the ghost of his first wife as the means of grieving his loss in a fatalistic anti-theism that feels downright religious.

For Hardy, as Claire Tomlin writes in her biography, there are three Emma’s: “Sometimes she appears as a ghost, sometimes as the elderly woman who liked parties and hats; more often as the girl of long ago, wearing an ‘air-blue gown,’ or with her ‘bright hair flapping free.’” Hardy names her (“woman much missed”), recalls their slow-dissolving marriage (“scars of the old flame”), owns up to their mutual failures (“things were not lastly as firstly well / with us”), and measures her apparitional lingering, postmortem, in places where she shadows him (“how you call to me, call to me, / Saying that you are not as you were”). He resurrects her girlish form, the woman he began courting long ago, (“fair-eyed and white shouldered, broad-browed and brown-tressed”).

For her turn, Emma (“a voiceless ghost,” “a phantom horsewoman”) seems to desire his harrowing her, having upped her agency as the restless spirit of his dead wife who now has, through him, a voice of her own. One of the elegies, “The Haunting,” is written from Emma’s point-of-view, first-person. From the crypt, she confesses that she is his partner in turmoil and that Hardy “Never . . . sees my faithful phantom / Though he speaks thereto.” Throughout, it seems that only these meditative odes of a night-ambling dramatist can penetrate “her shade,” one that soon will “vanish from me” when “the stars close their shutters and the dawn whitens hazily.” Emma has a consciousness all her own, freed, as it were, from her own sentence as a soul relieved of earthly strife.

Though Hardy abandoned Christianity, his abandonment of the religious idea of a soul became a major theme: how the faith’s salvific mission animates and insists on our helplessness in the face of eternity. His 1910 “God’s Funeral” manifests the fading deity as “throbs of thought.” Anymore, God is understood as “this phantasmal variousness,” humankind’s “self-deceived” creation: “Our making soon our maker did we deem, / And what we had imagined we believed.” The Anglican Redeemer of Hardy’s youth has “ceased to be,” though not entirely. Despite his unbelief, Hardy characterizes a bereft God who retains a universe-sized urge for retribution—perhaps because of humankind’s revolt against his dictate. Irving Howe writes that novelist and poet Hardy, unable to fully shed his Christian creatureliness, set himself an impossible task: to “convey the oppressiveness of fatality without positing an agency determining the course of fate.” If soul is fate, abandoning the soul frees us from the fatalistic.

As such, Hardy, the lyric bluesman, cannot shake Emma’s graveyard moan. Whether remembering her soulfulness in life or imagining her ghost in death—alternately a pre-dead and a post-dead spouse—he is bedeviled, his Christian conscience pricked, by her memory. And yet he compels her agency as a spiritual vehicle when she would rather (in Hardy’s characterization) be taken by the worms. The undead are alive because we the living won’t let them go.

In essence, Hardy, haunted by Emma’s spirit, joins with that spirit—in verse—for the sake not of settling her afterlife but of manifesting his grief with poetry. This “she” that Hardy loves and misses abides nowhere else in his writing but in these elegies. She is so well drawn in poetry that any life or agency outside his calculating lines has become her lot. And even if Emma possesses a being different than her husband’s abracadabra, what does it matter? She won’t get far. Not with the stingy Hardy who gives her soul no heavenly reward to hold onto and whose self (her Taoist no-self, perhaps) is only an object of his will.

And yet Hardy cannot shake the brooding character of Emma’s spooky presence—as if death has given her new panoramic life, the age-fixed women in each of her multiple personae and emotions. After unhinging her many moods, recreating their dailiness and their estrangement as a couple, Hardy only intensifies the loss, which, he seems to say in these poems, cannot be borne.

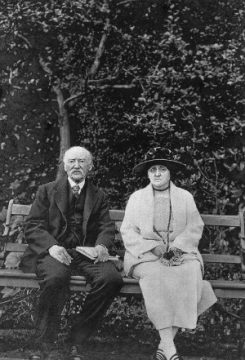

Bearing her loss, he lives in the disjunction between her presence and absence, her spirit and his memory. Though Hardy is done with religion and God, he assumes the role of revivalist and redeemer—re-embodying her, forgiving himself, and energizing his bereavement like Orpheus as he journeys to the underworld (his poetic faculty) to retrieve her spirit. Emma is incarnated as literary language, serving her penance in rhetorical rhymes. (Hardy stretches this technique in “Voices from Things Growing in a Churchyard.” In it, the dead live on, given feisty autobiographical character as they become plants festooned throughout a cemetery.) Thirteen months after Emma’s demise, the less aggrieved and more buoyed poet, his sentimentality erased, marries his secretary, Florence Dugdale, who is thirty-nine years his junior. While he composed his elegies to Emma, she moved into his home and may have been both anchor and prize for finishing the sequence.

What a year it was, 1913, when one of the great Victorian novelists transmuted his narrative genius into a personally redemptive and supple poetry. He did so, in part, as he reshaped the soul of his dead wife and its recalcitrance into spirit. Her spirit was adrift in him and fled from what her Anglican contemporaries would have called one’s “eternal rest.” But verbal description alone does not end the authoritarianism of the afterlife in which those who are so inclined must meet their comeuppance. Literature cannot escape the stereotypes already accumulated in its tropes and schemes, especially that yearned-for peace countless poets from Ovid to Mary Oliver seem to guarantee awaits us in the beyond.

Reading Hardy’s elegies, future poets have had a lodestone from which they could unloosen the bindings of the dichotomy between the body that was and the soul that is set free, a quid pro quo, if you will. They saw how to cultivate some new shoots from the religious sensibilities of Christian and humanist verse, and they discovered (they still do) new affinities for the enigma of spiritual transmutation and the nonreligious soul.