by Tim Sommers

In Democracy in America (1848), Alexis de Tocqueville concluded from his travels in the United States that “The particular and predominating fact peculiar to” this democratic age “is equality of conditions, and the chief passion which stirs men at such times is the love of this same equality.” Indeed, “The gradual progress of equality,” he wrote, “is something fated. The main features of this progress are the following: it is universal and permanent, it is daily passing beyond human control, and every event and every man helps it along….”

If this is at all accurate, it seems fair to say that our conditions, and our ambitions, regarding human equality, are much diminished. But I want to draw attention to just one specific point de Tocqueville highlights.

Equality, the relevant kind of equality for him, is “equality of conditions”. It’s not abstract moral equality or equality limited to political decision making or equality of opportunity or (as contemporary philosophers say) equality in the distribution of some underlying abstraction like utility, access to advantage, or primary goods. Democracy, and the democratic spirit, called on and depended on, for de Tocqueville, a certain level of real, actual, surface-level equality. The love of equality, that he is both drawn to and repelled by – with “a kind of religious dread” – is just ordinary equality, not some philosophical surrogate.

If you ask someone at a random about equality or inequality in the United States today, they will very likely assume you mean economic inequality. This is partly because economic inequality has gotten more attention recently, but it is mostly because, if you ask people to think about whether the conditions of their life are equal or unequal to the conditions of others’ lives, the first thing many will think about is money.

Yet, at the precise moment Thomas Piketty’s groundbreaking work on economic inequality was drawing new attention to the shocking level of economic inequality that characterizes our new gilded age, philosopher Harry Frankfurt thought it imperative to insist that “Insofar as economic inequality is undesirable…this is not because it is as such morally objectionable. As such, it is not morally objectionable.” Rather, he said, “from a moral point of view economic inequality does not matter very much”.

Unfortunately, many other philosophers writing about economic inequality also deny that it is bad in and of itself. Instead, they insist that substantial economic inequalities are bad because, and where, they have bad effects.

I believe this view is a mistake. Read more »

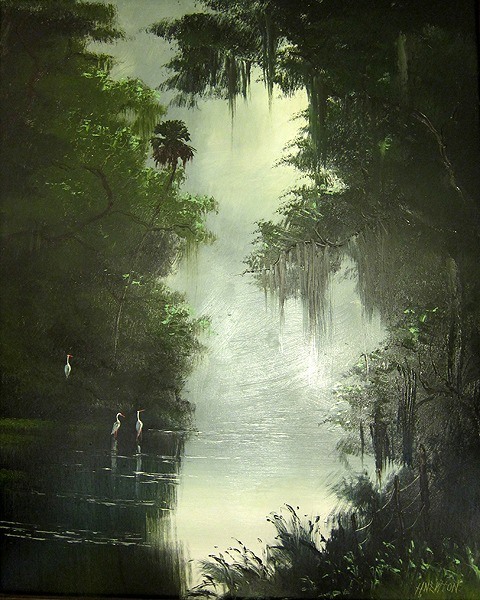

Harold Newton. Untitled, 1960s.

Harold Newton. Untitled, 1960s.

researchers, as well. Indeed,

researchers, as well. Indeed,

Louise Bourgeois

Louise Bourgeois

On January 28th of this year, just as the biggest

On January 28th of this year, just as the biggest  I majored in English in college.

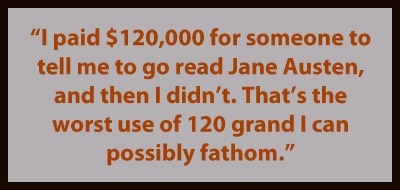

I majored in English in college. During the 1920s, Frank Ramsey made massive contributions to no fewer than four disciplines: philosophy, economics, mathematics and subjective utility theory. In 1999, the philosopher Donald Davidson caught his brilliance by coining the term the “Ramsey Effect”: when you discover that your exciting and apparently original philosophical discovery has already been presented, and presented more elegantly, by Frank Ramsey.

During the 1920s, Frank Ramsey made massive contributions to no fewer than four disciplines: philosophy, economics, mathematics and subjective utility theory. In 1999, the philosopher Donald Davidson caught his brilliance by coining the term the “Ramsey Effect”: when you discover that your exciting and apparently original philosophical discovery has already been presented, and presented more elegantly, by Frank Ramsey. In the 1970s, the late mathematician Paul Cohen, the only person to ever win a Fields Medal for work in mathematical logic,

In the 1970s, the late mathematician Paul Cohen, the only person to ever win a Fields Medal for work in mathematical logic,  The U.S. government has never been a consistent promoter of human rights — other interests were often prioritized — but when it did act, it could be powerful. Yet U.S. influence on human rights has plummeted under President Donald Trump. If Joe Biden assumes the presidency, he will need to oversee a major transformation if he wants the U.S. government to be a credible human rights voice.

The U.S. government has never been a consistent promoter of human rights — other interests were often prioritized — but when it did act, it could be powerful. Yet U.S. influence on human rights has plummeted under President Donald Trump. If Joe Biden assumes the presidency, he will need to oversee a major transformation if he wants the U.S. government to be a credible human rights voice. Asad Raza’s expansive cross-disciplinary practice defies categorization. Situated somewhere between performance, installation and curation, its elusiveness can be attributed to many factors. Primary to these is the fact that Raza’s work rejects the rigid prescriptiveness that these disciplines often demand. Rather, his open-ended, site-specific installations supply fertile ground for interaction, ideas and communities to develop. In his piece ‘Absorption’, currently on view at Gropius Bau as part of ‘

Asad Raza’s expansive cross-disciplinary practice defies categorization. Situated somewhere between performance, installation and curation, its elusiveness can be attributed to many factors. Primary to these is the fact that Raza’s work rejects the rigid prescriptiveness that these disciplines often demand. Rather, his open-ended, site-specific installations supply fertile ground for interaction, ideas and communities to develop. In his piece ‘Absorption’, currently on view at Gropius Bau as part of ‘ All the facts are already known, and against each fact the supporters of Donald Trump have woven careful rationalizations. The truths are ugly, and so they have been festooned with kitschy trappings; some fall from the lips of a First Lady who speaks of bringing Americans together in a dress that costs about what the average female wage-earner in the United States makes in a month. I imagine the homes of Trump supporters as staging areas for transforming these ugly truths: the 186,000 Covid-19 death toll wrapped in duct tape and Trump’s yellow ties until it cannot be seen, and set down in a corner. Also in that dark corner we see factual information about Kamala Harris’s birthplace in Oakland, California, rejected—her birth certificate obscured with black lettering that shouts foreigner, “anchor baby,” alien, spy, and bitch. In this way, millions of factories of false facts are slapped-and-dashed together in the homes of Trump’s supporters to create a world that accords with the words of their leader. There is no arsenal of truth that can penetrate into their homes or their hearts.

All the facts are already known, and against each fact the supporters of Donald Trump have woven careful rationalizations. The truths are ugly, and so they have been festooned with kitschy trappings; some fall from the lips of a First Lady who speaks of bringing Americans together in a dress that costs about what the average female wage-earner in the United States makes in a month. I imagine the homes of Trump supporters as staging areas for transforming these ugly truths: the 186,000 Covid-19 death toll wrapped in duct tape and Trump’s yellow ties until it cannot be seen, and set down in a corner. Also in that dark corner we see factual information about Kamala Harris’s birthplace in Oakland, California, rejected—her birth certificate obscured with black lettering that shouts foreigner, “anchor baby,” alien, spy, and bitch. In this way, millions of factories of false facts are slapped-and-dashed together in the homes of Trump’s supporters to create a world that accords with the words of their leader. There is no arsenal of truth that can penetrate into their homes or their hearts. In 2019, a

In 2019, a