Susan Glasser in The New Yorker:

Does anything matter anymore in American politics? In the week since Donald Trump’s Convention ended with a personality-cult party on the White House lawn, the President has completely refocussed his campaign on threats to law and order from “Rioters, Anarchists, Agitators, and Looters.” He has suggested there will be a “Rigged Election”; urged supporters in North Carolina to commit election fraud, by voting twice; and likened protesters demanding racial justice to “Domestic Terrorists.” The President personally ordered a review of federal aid, with the goal of withholding funds from “anarchist” Democratic-run cities that have allowed “themselves to deteriorate into lawless zones.” And he has baselessly alleged that his Democratic opponent, Joe Biden, is taking some sort of “enhancement” drug, and claimed that Biden is the pawn of shadowy “dark forces.”

Does anything matter anymore in American politics? In the week since Donald Trump’s Convention ended with a personality-cult party on the White House lawn, the President has completely refocussed his campaign on threats to law and order from “Rioters, Anarchists, Agitators, and Looters.” He has suggested there will be a “Rigged Election”; urged supporters in North Carolina to commit election fraud, by voting twice; and likened protesters demanding racial justice to “Domestic Terrorists.” The President personally ordered a review of federal aid, with the goal of withholding funds from “anarchist” Democratic-run cities that have allowed “themselves to deteriorate into lawless zones.” And he has baselessly alleged that his Democratic opponent, Joe Biden, is taking some sort of “enhancement” drug, and claimed that Biden is the pawn of shadowy “dark forces.”

On his Twitter feed, Trump repeatedly promoted misinformation about the ongoing coronavirus pandemic while also attacking “Crazy Nancy Pelosi”; the “highly political” National Basketball Association; the governor of Oregon; the “wacky Radical Left Do Nothing Democrat Mayor of Portland”; the governor of New York, Andrew Cuomo, and his brother, CNN’s Chris Cuomo; and various other figures in the “Enemy of the People” media, including the conservative Internet aggregator Matt Drudge and MSNBC’s “very untalented” Joy Reid. Trump’s Administration, meanwhile, is withholding briefings on election interference by Russia and other foreign powers from congressional intelligence committees and telling leaders in key battleground states to be prepared for a coronavirus vaccine, which may be approved by the government just days before the election. And that’s just this week.

The rest of the news in Trump’s America, two months before Election Day, is equally gutting: twenty or so U.S. states have rising cases of covid-19, and, as many schools and universities reopen, the numbers are expected to grow. On many days, more than a thousand Americans die as a result of the pandemic. By comparison, in the worst week of the Vietnam War, just more than five hundred American personnel died, the national-security expert and former C.I.A. official David Priess noted. All told, American deaths from covid-19 are approaching two hundred thousand. Mass unemployment continues, and many companies are bracing for new, more permanent layoffs. Food banks are overwhelmed. Congress, stuck in an impasse between House Democrats and Senate Republicans, has failed to pass a new round of economic relief, and the initial aid package for small businesses and the unemployed has run out. The national debt as a share of the economy has reached its highest level since the Second World War.

None of this, apparently, has any electoral consequence.

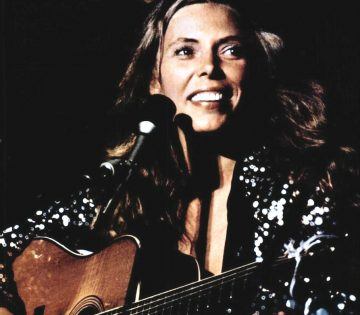

When Joni Mitchell first came to prominence, in the late-1960s “Summer of Love” era, she was often perceived as a kind of “poetess” or “nightingale” folk singer: a putatively pure origin of beautifully natural-seeming songs (“The Circle Game,” “Chelsea Morning, and “Both Sides, Now,” among many others). When the rapper Q-Tip declared (on Janet Jackson’s 1997 song “Got ’Til it’s Gone”) that “Joni Mitchell never lies,” he articulated a familiar understanding of the singer as, above all, truthful and authentic.

When Joni Mitchell first came to prominence, in the late-1960s “Summer of Love” era, she was often perceived as a kind of “poetess” or “nightingale” folk singer: a putatively pure origin of beautifully natural-seeming songs (“The Circle Game,” “Chelsea Morning, and “Both Sides, Now,” among many others). When the rapper Q-Tip declared (on Janet Jackson’s 1997 song “Got ’Til it’s Gone”) that “Joni Mitchell never lies,” he articulated a familiar understanding of the singer as, above all, truthful and authentic.

It’s not unusual for geochronologist Rainer Grün to bring human bones back with him when he returns home to Australia from excursions in Europe or Asia. Jawbones from extinct hominins in Indonesia, Neanderthal teeth from Israel, and ancient human finger bones unearthed in Saudi Arabia have all at one point spent time in his lab at Australian National University before being returned home. Grün specializes in developing methods to discern the age of such specimens. In 2016, he carried with him a particularly precious piece of cargo: a tiny sliver of fossilized bone covered in bubble wrap inside a box.

It’s not unusual for geochronologist Rainer Grün to bring human bones back with him when he returns home to Australia from excursions in Europe or Asia. Jawbones from extinct hominins in Indonesia, Neanderthal teeth from Israel, and ancient human finger bones unearthed in Saudi Arabia have all at one point spent time in his lab at Australian National University before being returned home. Grün specializes in developing methods to discern the age of such specimens. In 2016, he carried with him a particularly precious piece of cargo: a tiny sliver of fossilized bone covered in bubble wrap inside a box. Does anything matter anymore in American politics? In the week since

Does anything matter anymore in American politics? In the week since  The truth is that Uber and Lyft exist largely as the embodiments of Wall Street-funded bets on automation, which have

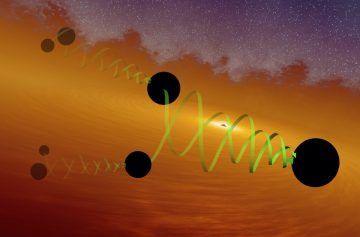

The truth is that Uber and Lyft exist largely as the embodiments of Wall Street-funded bets on automation, which have  The LIGO/VIRGO collaboration has picked up a gravitational wave signal from another black-hole merger—and it’s one for the record books.

The LIGO/VIRGO collaboration has picked up a gravitational wave signal from another black-hole merger—and it’s one for the record books. We are living in a remarkable moment, in fact a moment unique in human history. It is a moment of confluence of severe crises, at least four, which threaten the survival of organized human life on earth, not in the distant future.

We are living in a remarkable moment, in fact a moment unique in human history. It is a moment of confluence of severe crises, at least four, which threaten the survival of organized human life on earth, not in the distant future.

As scientists edge closer to creating a vaccine against the SARS-CoV-2 coronavirus, Indian pharmaceutical companies are front and centre in the race to supply the world with an effective product. But researchers worry that, even with India’s experience as a vaccine manufacturer, its companies will struggle to produce enough doses sufficiently fast to bring its own huge outbreak under control. On top of that, it will be an immense logistical challenge to distribute the doses to people in rural and remote regions.

As scientists edge closer to creating a vaccine against the SARS-CoV-2 coronavirus, Indian pharmaceutical companies are front and centre in the race to supply the world with an effective product. But researchers worry that, even with India’s experience as a vaccine manufacturer, its companies will struggle to produce enough doses sufficiently fast to bring its own huge outbreak under control. On top of that, it will be an immense logistical challenge to distribute the doses to people in rural and remote regions. The scientists crowded around Yuanchao Xue’s petri dish. They couldn’t identify the cells that they were seeing. “We saw a lot of cells with spikes growing out of the cell surface,” said Xiang-Dong Fu, the research team’s leader at the University of California, San Diego. “None of us really knew that much about neuroscience, and we asked around and someone said that these were neurons.” The team, who were made up of basic cellular and molecular scientists, were utterly puzzled. Where had these neurons come from? Xue had left a failed experiment, a dish full of human tumor cells, in the incubator, and when he looked two weeks later, he found a dish full of neurons.

The scientists crowded around Yuanchao Xue’s petri dish. They couldn’t identify the cells that they were seeing. “We saw a lot of cells with spikes growing out of the cell surface,” said Xiang-Dong Fu, the research team’s leader at the University of California, San Diego. “None of us really knew that much about neuroscience, and we asked around and someone said that these were neurons.” The team, who were made up of basic cellular and molecular scientists, were utterly puzzled. Where had these neurons come from? Xue had left a failed experiment, a dish full of human tumor cells, in the incubator, and when he looked two weeks later, he found a dish full of neurons. Is the individual person a composite of a material body and an immaterial mind or soul? And if so, what is the relationship between these two ingredients?

Is the individual person a composite of a material body and an immaterial mind or soul? And if so, what is the relationship between these two ingredients? The work of cultural criticism never ends. A hundred years ago, Thomas R. Marshall, Woodrow Wilson’s vice president, proclaimed that “what this country needs is a really good five-cent cigar.” But who would say that now? Times have changed, tobacco has become an evil weed, and anyway, what the country needs now is a really good four-letter word.

The work of cultural criticism never ends. A hundred years ago, Thomas R. Marshall, Woodrow Wilson’s vice president, proclaimed that “what this country needs is a really good five-cent cigar.” But who would say that now? Times have changed, tobacco has become an evil weed, and anyway, what the country needs now is a really good four-letter word. In Henry IV, Part One, Shakespeare’s Hotspur turns on his prissy wife: “Heart! You swear like a comfit-maker’s wife. ‘Not you in good sooth!’ and ‘as true as I live!’”. Instead Hotspur demanded a good mouth-filling oath. Something like his own “By God’s heart” was more suited to a lady of rank.

In Henry IV, Part One, Shakespeare’s Hotspur turns on his prissy wife: “Heart! You swear like a comfit-maker’s wife. ‘Not you in good sooth!’ and ‘as true as I live!’”. Instead Hotspur demanded a good mouth-filling oath. Something like his own “By God’s heart” was more suited to a lady of rank. For nearly three full centuries, the most accurate way that humanity kept track of time was through

For nearly three full centuries, the most accurate way that humanity kept track of time was through