Sarah Neilson at The Seattle Times:

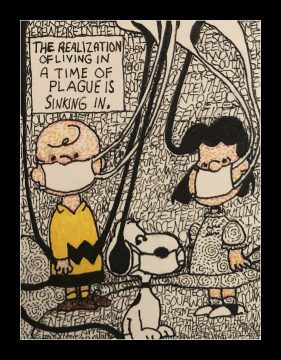

The words social distancing have already defined 2020, and everyone is already tired of them (and coronavirus, for that matter). Despite how terrible it feels to not be close to people, this is what community care looks like right now. Luckily, books still exist, and can be their own vehicle for connection. And what better reading material for right now than books where the characters are, in some way, alone? None of these are dystopian (at least not in the traditional sense), but are instead characterized by protagonists with complex interior lives who are either isolated (in some way that’s not about a contagion) or fiercely independent, or both. Happy introverting, readers!

The words social distancing have already defined 2020, and everyone is already tired of them (and coronavirus, for that matter). Despite how terrible it feels to not be close to people, this is what community care looks like right now. Luckily, books still exist, and can be their own vehicle for connection. And what better reading material for right now than books where the characters are, in some way, alone? None of these are dystopian (at least not in the traditional sense), but are instead characterized by protagonists with complex interior lives who are either isolated (in some way that’s not about a contagion) or fiercely independent, or both. Happy introverting, readers!

“My Morningless Mornings” by Stefany Anne Golberg

If you’re ready to get cerebral while also being hypnotized by prose, this slim memoir is perfect. Golberg writes about isolating herself in the night, rejecting the world’s attachment to day. The dark brings on all kinds of meditation on psychology, death, art and what it means to be awake. This might be the ultimate quarantine read.

more here.

O

O As the new coronavirus marches around the globe, countries with escalating outbreaks are eager to learn whether China’s extreme lockdowns were responsible for bringing the crisis there under control. Other nations are now following China’s lead and limiting movement within their borders, while dozens of countries have restricted international visitors. In mid-January, Chinese authorities introduced unprecedented measures to contain the virus, stopping movement in and out of Wuhan, the centre of the epidemic, and 15 other cities in Hubei province — home to more than 60 million people. Flights and trains were suspended, and roads were blocked. Soon after, people in many Chinese cities were told to stay home and venture out only to get food or medical help. Some 760 million people, roughly half the country’s population, were confined to their homes, according to the

As the new coronavirus marches around the globe, countries with escalating outbreaks are eager to learn whether China’s extreme lockdowns were responsible for bringing the crisis there under control. Other nations are now following China’s lead and limiting movement within their borders, while dozens of countries have restricted international visitors. In mid-January, Chinese authorities introduced unprecedented measures to contain the virus, stopping movement in and out of Wuhan, the centre of the epidemic, and 15 other cities in Hubei province — home to more than 60 million people. Flights and trains were suspended, and roads were blocked. Soon after, people in many Chinese cities were told to stay home and venture out only to get food or medical help. Some 760 million people, roughly half the country’s population, were confined to their homes, according to the  To understand why the world economy is in grave peril because of the spread of coronavirus, it helps to grasp one idea that is at once blindingly obvious and sneakily profound.

To understand why the world economy is in grave peril because of the spread of coronavirus, it helps to grasp one idea that is at once blindingly obvious and sneakily profound. “What good is half a wing?” That’s the rhetorical question often asked by people who have trouble accepting Darwin’s theory of evolution by natural selection. Of course it’s a very answerable question, but figuring out what exactly the answer is leads us to some fascinating biology. Neil Shubin should know: he is the co-discoverer of

“What good is half a wing?” That’s the rhetorical question often asked by people who have trouble accepting Darwin’s theory of evolution by natural selection. Of course it’s a very answerable question, but figuring out what exactly the answer is leads us to some fascinating biology. Neil Shubin should know: he is the co-discoverer of  I have never been much of a runner, but on Saturday I find myself suiting up for exercise and meeting a friend for a run. It has been a week since the Italian prime minister

I have never been much of a runner, but on Saturday I find myself suiting up for exercise and meeting a friend for a run. It has been a week since the Italian prime minister  The Belgrade installation of Sound Corridor missed an opportunity to connect Abramović’s work to that of her contemporaries. But it was nevertheless a startling introduction to an exhibition with a haunting soundscape, evocative of melancholy, death, and nostalgic enchantment. Moving from the corridor of recorded gunfire into the lobby, one could hear Abramović’s screams from the video Freeing the Voice (1975) on the second floor. For that performance at the SKC, the artist lay on her back screaming for three hours, until she lost her voice. On the first floor, a large but quiet black-box installation featured video footage from The Artist Is Present (2010), the performance staged during her retrospective at New York’s Museum of Modern Art. Opposite this installation stood Private Archaeology (1997–2015), a set of wooden cabinets holding a collection of sketches, collages, artifacts, and ephemera from Abramović’s archive, a deeply self-mythologizing installation that surprisingly did not include any reference to her SKC involvement. At the top of the stairs, large projections showed black-and-white footage of some of Abramović’s best-known works: Freeing the Voice, mentioned above; Freeing the Body (1976), in which she wrapped her head in a black scarf and danced for eight hours, until she collapsed; and several of her performances made in collaboration with German artist Ulay, including one where they slam their bodies together, and another where they sit opposite each other and scream.

The Belgrade installation of Sound Corridor missed an opportunity to connect Abramović’s work to that of her contemporaries. But it was nevertheless a startling introduction to an exhibition with a haunting soundscape, evocative of melancholy, death, and nostalgic enchantment. Moving from the corridor of recorded gunfire into the lobby, one could hear Abramović’s screams from the video Freeing the Voice (1975) on the second floor. For that performance at the SKC, the artist lay on her back screaming for three hours, until she lost her voice. On the first floor, a large but quiet black-box installation featured video footage from The Artist Is Present (2010), the performance staged during her retrospective at New York’s Museum of Modern Art. Opposite this installation stood Private Archaeology (1997–2015), a set of wooden cabinets holding a collection of sketches, collages, artifacts, and ephemera from Abramović’s archive, a deeply self-mythologizing installation that surprisingly did not include any reference to her SKC involvement. At the top of the stairs, large projections showed black-and-white footage of some of Abramović’s best-known works: Freeing the Voice, mentioned above; Freeing the Body (1976), in which she wrapped her head in a black scarf and danced for eight hours, until she collapsed; and several of her performances made in collaboration with German artist Ulay, including one where they slam their bodies together, and another where they sit opposite each other and scream. During World War I, when soldiers thought longingly of home, their minds often turned to the garden. Indeed, they made small gardens in the trenches, planting bulbs in empty brass shell-casings. In a catalog essay, the Garden Museum’s director, Christopher Woodward, quotes Ford Madox-Ford’s No Enemy: A Tale of Reconstruction (1929), on the soldier’s dream of return, not to a landscape but “a nook rather,” at the end of a valley “with a little stream, just a trickle level with the grass of the bottom. You understand the idea—a sanctuary.” So the focus of the show is not on great estates but on domestic landscapes and individual plants, and implicitly on the garden’s allegorical power: the myths of Eden.

During World War I, when soldiers thought longingly of home, their minds often turned to the garden. Indeed, they made small gardens in the trenches, planting bulbs in empty brass shell-casings. In a catalog essay, the Garden Museum’s director, Christopher Woodward, quotes Ford Madox-Ford’s No Enemy: A Tale of Reconstruction (1929), on the soldier’s dream of return, not to a landscape but “a nook rather,” at the end of a valley “with a little stream, just a trickle level with the grass of the bottom. You understand the idea—a sanctuary.” So the focus of the show is not on great estates but on domestic landscapes and individual plants, and implicitly on the garden’s allegorical power: the myths of Eden. When Stone mustered out of the navy in the late fifties, the United States had perhaps reached its zenith in terms of economic success and dominance, political hegemony worldwide, and a vibrant and vigorous culture, ripe for exportation in multiple embodiments: from serious literature and high art to B movies, pop music, and Coca-Cola. It seemed a national moment free of self-doubt—although a considerable dysphoria would soon begin to express itself, as the social upheavals of the sixties began. Stone, who did not begin the world from a position of privilege, was quicker than most to see the shadows cast by the rising American star. In his work, he would repeatedly portray those bright aspirations set off by a surrounding darkness that was likely in the end to devour them.

When Stone mustered out of the navy in the late fifties, the United States had perhaps reached its zenith in terms of economic success and dominance, political hegemony worldwide, and a vibrant and vigorous culture, ripe for exportation in multiple embodiments: from serious literature and high art to B movies, pop music, and Coca-Cola. It seemed a national moment free of self-doubt—although a considerable dysphoria would soon begin to express itself, as the social upheavals of the sixties began. Stone, who did not begin the world from a position of privilege, was quicker than most to see the shadows cast by the rising American star. In his work, he would repeatedly portray those bright aspirations set off by a surrounding darkness that was likely in the end to devour them. The term “bird’s nest” has come to describe a messy hairdo, tangled fishing line and other unspeakably knotty conundrums. But that does birds an injustice. Their tiny brains, dense with neurons, produce marvels that have long captured scientific interest as naturally selected engineering solutions — yet nests are still not well understood. One effort to disentangle the structural dynamics of the nest is underway in the sunny yellow lab — the Mechanical Biomimetics and Open Design Lab — of Hunter King, an experimental soft-matter physicist at the University of Akron in Ohio. “We hypothesize that a bird nest might effectively be a disordered stick bomb, with just enough stored energy to keep it rigid,” Dr. King said. He is the principal investigator of an ongoing study, with

The term “bird’s nest” has come to describe a messy hairdo, tangled fishing line and other unspeakably knotty conundrums. But that does birds an injustice. Their tiny brains, dense with neurons, produce marvels that have long captured scientific interest as naturally selected engineering solutions — yet nests are still not well understood. One effort to disentangle the structural dynamics of the nest is underway in the sunny yellow lab — the Mechanical Biomimetics and Open Design Lab — of Hunter King, an experimental soft-matter physicist at the University of Akron in Ohio. “We hypothesize that a bird nest might effectively be a disordered stick bomb, with just enough stored energy to keep it rigid,” Dr. King said. He is the principal investigator of an ongoing study, with

I must admit that when I first flipped through Capitalism on Edge: How Fighting Precarity Can Achieve Radical Change Without Crisis or Utopia by Albena Azmanova, it did not look too inviting. The blurbs on the jacket did nothing to reassure me, suggesting that this was yet another post-Marxist critique of greedy capitalists and their enablers. As it turns out, it is, but in a way that is more interesting than I had assumed. As soon as I started reading the Introduction, I was gripped by the lucidity of ideas and clarity of the prose. For an academic text written from the perspective of Critical Theory, this is a wonderfully direct, incisive and insightful book. One does not need to agree with all the details of the analysis to find reading it a rewarding experience.

I must admit that when I first flipped through Capitalism on Edge: How Fighting Precarity Can Achieve Radical Change Without Crisis or Utopia by Albena Azmanova, it did not look too inviting. The blurbs on the jacket did nothing to reassure me, suggesting that this was yet another post-Marxist critique of greedy capitalists and their enablers. As it turns out, it is, but in a way that is more interesting than I had assumed. As soon as I started reading the Introduction, I was gripped by the lucidity of ideas and clarity of the prose. For an academic text written from the perspective of Critical Theory, this is a wonderfully direct, incisive and insightful book. One does not need to agree with all the details of the analysis to find reading it a rewarding experience.

Sughra Raza. Mid-winter Fall. February 2020.

Sughra Raza. Mid-winter Fall. February 2020.