by Scott F. Aikin and Robert B. Talisse

Stoicism has been enjoying a renaissance lately. Popular books with Stoic advice are widespread, it’s being marketed as a life-hack, and now with the global coronavirus pandemic, Stoicism is a regular touchstone in prescriptions for maintaining sanity in troubled times. It’s not difficult to see why Stoicism is making a comeback. We’re facing difficult days, and the core insight of Stoic value theory is the grand division between what is up to us and what is not. Our mental life, what we think, to what we direct our attention, how we accept or reject ideas, and how we exercise our wills, are all up to us. And then there’s everything else: money, fame, health, status, and how things in the world generally go. If we attend only to the things in the first category (namely, that we maintain our cool, that we are critical thinkers, and we do our duty), then we will never be disappointed, because those are things up to us. But if we fixate on the latter things, then we are doomed to anxiety and disappointment, because those are things that are not up to us. Epictetus’ Enchiridion famously opens with this observation, and all Stoic ethics is driven by this intuitive distinction. However, a number of difficulties arise once one prescribes Stoicism as a coping strategy.

To start, there is what we’ve elsewhere called the “Stoicism for dark days problem.” Here it is in a nutshell. For Stoicism to do the work it promises as a coping strategy, we must not only practice Stoicism when things go badly, but also when things go well. You can’t turn Stoicism on when you need to weather dark days, since in order to do that you’d need to judge that things are going badly. But according to Stoicism, the only thing that could go badly (or well) is one’s exercise of judgment; thus, to exercise one’s judgment in light of an assessment that things are going badly is to commit an error that implicitly denies Stoicism. Instead, you need to be a Stoic during the good times, too. In his Meditations, Marcus Aurelius observes the problem of being double-minded between Stoic values and non-Stoic values when thinking about one’s life – he notes that it all too often results in confusion or incoherence (M 5.12). The trouble is that all of the attractions of Stoicism when it is offered as a consolation in trying times actually undercut the Stoic’s fundamental message. Read more »

Kazuo Shiraga. Untitled 1964.

Kazuo Shiraga. Untitled 1964. There has been much discussion lately of whether the COVID-19 pandemic will spell the end of globalization. It’s hard to get economists to agree on the meaning of the numbers, or foreign policy analysts to commit to a vision of the future in a world that changes from one moment to the next. Globalization means different things to different people and entities. Its many facets, and many narratives about those facets, complicate discussion about either a contraction or a resurgence of globalization. For corporations, it means access to inexpensive labor markets; for money managers, it means access to capital markets. For the typical business traveler, it may mean something as basic as greater choice of airlines and flight times for an international trip. For an optimistic humanist, it might symbolize enhanced international cooperation and a suppression of nationalism and xenophobia. For an environmentalist, it is marred by the dangerous policies that accelerate climate change. For a technocrat, it seems the obvious economic approach to accompany the paradigm of social-media-fueled connectedness, data collection, surveillance, and targeted marketing.

There has been much discussion lately of whether the COVID-19 pandemic will spell the end of globalization. It’s hard to get economists to agree on the meaning of the numbers, or foreign policy analysts to commit to a vision of the future in a world that changes from one moment to the next. Globalization means different things to different people and entities. Its many facets, and many narratives about those facets, complicate discussion about either a contraction or a resurgence of globalization. For corporations, it means access to inexpensive labor markets; for money managers, it means access to capital markets. For the typical business traveler, it may mean something as basic as greater choice of airlines and flight times for an international trip. For an optimistic humanist, it might symbolize enhanced international cooperation and a suppression of nationalism and xenophobia. For an environmentalist, it is marred by the dangerous policies that accelerate climate change. For a technocrat, it seems the obvious economic approach to accompany the paradigm of social-media-fueled connectedness, data collection, surveillance, and targeted marketing.

1. As the coronavirus continues to disrupt human life in many corners of the globe, a phrase from George Frideric Handel’s Messiah has wormed its way through the background noise of my attention span. It occurs in a Part III

1. As the coronavirus continues to disrupt human life in many corners of the globe, a phrase from George Frideric Handel’s Messiah has wormed its way through the background noise of my attention span. It occurs in a Part III  We get half a sunny day every other day since Corona has coaxed us to quit public spaces. In the past fortnight or so, sunlight has been in short supply just as masks, disinfectant spray and toilet paper. When the sun is out, it’s no ordinary gift; it brings a rush of joy that wipes out not only the free-floating, dystopic COVID -19 anxiety, but also the other recent traumas we’ve faced as a family. Indoors, socially-distant by three feet, hunched over our phones for news of loved ones, we forget it is spring, but mornings the sunlight hits the windows feel as if God has turned on the power-wash setting: one is shocked into vigor, tricked into optimism. On such a day, I step down the patio threshold as if pulled by a magnet; just out of the shower and still combing my wet hair, I’m suddenly aware of another gift— soap.

We get half a sunny day every other day since Corona has coaxed us to quit public spaces. In the past fortnight or so, sunlight has been in short supply just as masks, disinfectant spray and toilet paper. When the sun is out, it’s no ordinary gift; it brings a rush of joy that wipes out not only the free-floating, dystopic COVID -19 anxiety, but also the other recent traumas we’ve faced as a family. Indoors, socially-distant by three feet, hunched over our phones for news of loved ones, we forget it is spring, but mornings the sunlight hits the windows feel as if God has turned on the power-wash setting: one is shocked into vigor, tricked into optimism. On such a day, I step down the patio threshold as if pulled by a magnet; just out of the shower and still combing my wet hair, I’m suddenly aware of another gift— soap.

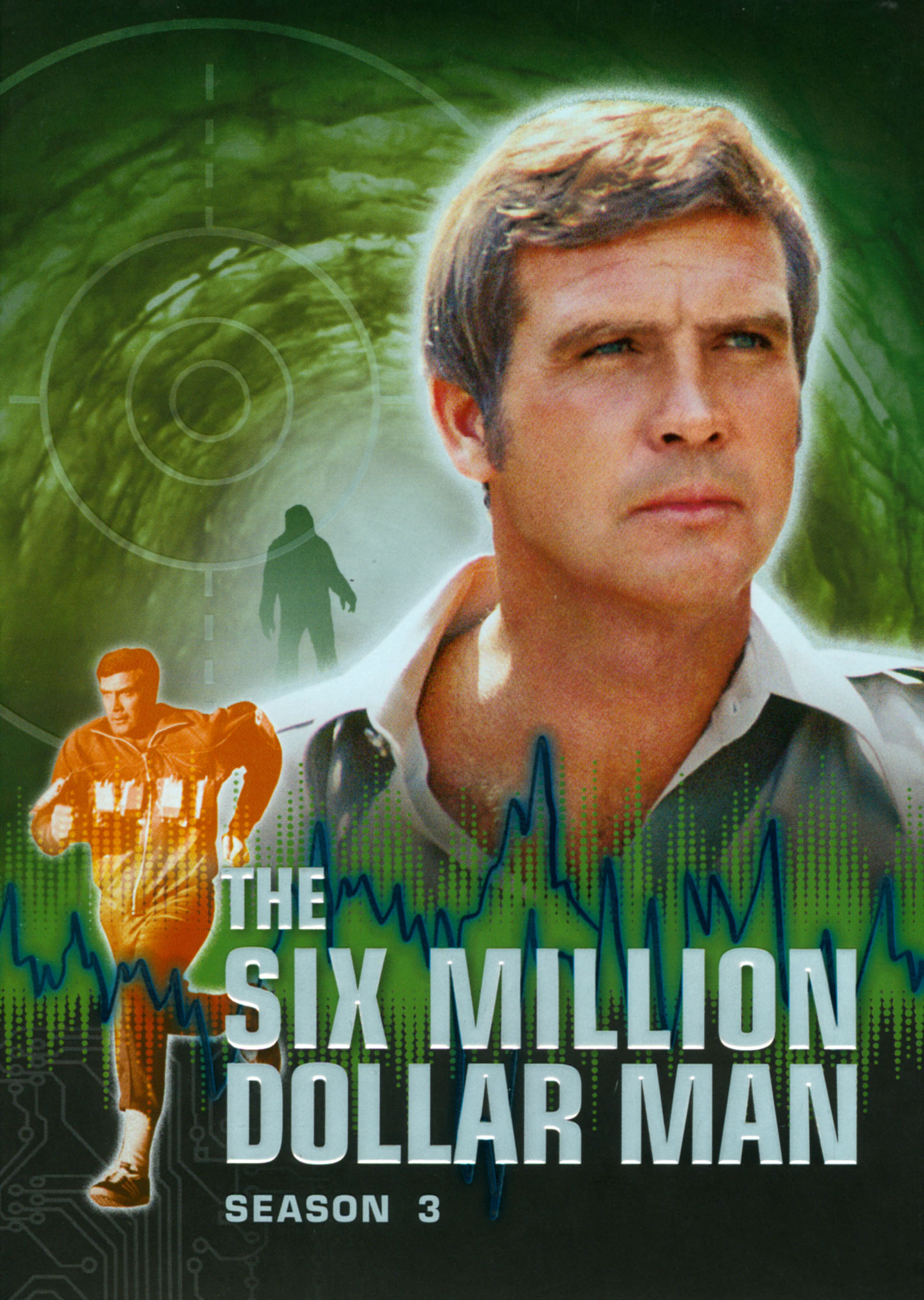

I was a minor mess in high school. Had no idea what to do with my curly hair. Unduly influenced by a childhood spent watching late ‘70s television, I stubbornly brushed it to the side in a vain attempt to straighten and shape it into a helmet à la The Six Million Dollar Man or countless B-actors on The Love Boat and Fantasy Island. I couldn’t muster any fashion beyond jeans, t-shirts, and Pumas. In the winter I wore a green army coat. In the summer it was shorts and knee high tube socks.

I was a minor mess in high school. Had no idea what to do with my curly hair. Unduly influenced by a childhood spent watching late ‘70s television, I stubbornly brushed it to the side in a vain attempt to straighten and shape it into a helmet à la The Six Million Dollar Man or countless B-actors on The Love Boat and Fantasy Island. I couldn’t muster any fashion beyond jeans, t-shirts, and Pumas. In the winter I wore a green army coat. In the summer it was shorts and knee high tube socks. When I became an attending physician at New York–Presbyterian’s Weill Cornell Hospital last summer, after graduating from a residency at Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston, I became a hospitalist: a doctor of general internal medicine who takes care of patients for the duration of their inpatient hospital care. Besides my own writing and research, I also teach medical students and residents in a variety of courses and electives. But for me, as for roughly a million other doctors in the United States, that regular routine is changing very suddenly. Part of the challenge we’re facing with Covid-19 is that even knowing this is an event of shocking magnitude, we are not yet able to measure or foresee exactly how fast the disease’s progress through the world’s population will be.

When I became an attending physician at New York–Presbyterian’s Weill Cornell Hospital last summer, after graduating from a residency at Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston, I became a hospitalist: a doctor of general internal medicine who takes care of patients for the duration of their inpatient hospital care. Besides my own writing and research, I also teach medical students and residents in a variety of courses and electives. But for me, as for roughly a million other doctors in the United States, that regular routine is changing very suddenly. Part of the challenge we’re facing with Covid-19 is that even knowing this is an event of shocking magnitude, we are not yet able to measure or foresee exactly how fast the disease’s progress through the world’s population will be.

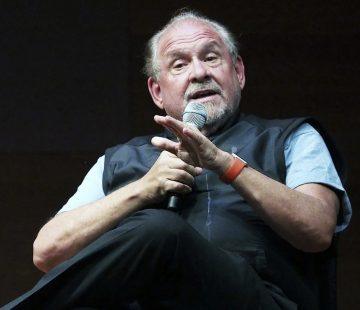

LARRY BRILLIANT SAYS

LARRY BRILLIANT SAYS