Sarah Resnick in Bookforum:

“I was diagnosed with breast cancer in 2014, at the age of forty-one,” the poet Anne Boyer writes early in her panoramic, book-length essay The Undying. Elemental and unadorned, the sentence does not leap out for quotation, and in the context of a review of some other essay, some other book, summary would be adequate (“At the age of forty-one, the poet Anne Boyer . . .”). But in a story about breast cancer, the voice of the speaker is consequential and Boyer makes this plain when, in consulting other women writers who suffered from the disease, she observes whether or not they have used the first person. Audre Lorde, for example, in The Cancer Journals (1980), her cancer memoir avant la lettre, has. Susan Sontag, who wrote Illness as Metaphor (1978) while being treated for the disease, has not. Boyer remarks on these choices not to find fault with them but to stress that decisions regarding whether and how to write about breast cancer are among its many agonies. The disease, she tells us, presents as “a disordering question of form.”

“I was diagnosed with breast cancer in 2014, at the age of forty-one,” the poet Anne Boyer writes early in her panoramic, book-length essay The Undying. Elemental and unadorned, the sentence does not leap out for quotation, and in the context of a review of some other essay, some other book, summary would be adequate (“At the age of forty-one, the poet Anne Boyer . . .”). But in a story about breast cancer, the voice of the speaker is consequential and Boyer makes this plain when, in consulting other women writers who suffered from the disease, she observes whether or not they have used the first person. Audre Lorde, for example, in The Cancer Journals (1980), her cancer memoir avant la lettre, has. Susan Sontag, who wrote Illness as Metaphor (1978) while being treated for the disease, has not. Boyer remarks on these choices not to find fault with them but to stress that decisions regarding whether and how to write about breast cancer are among its many agonies. The disease, she tells us, presents as “a disordering question of form.”

Before the 1970s, the subject of breast cancer was all but taboo, the disease stigmatized. Written traces of the illness could be found mostly in medical narratives, where men (doctors) were the actors and women mere hosts to the drama’s antagonists (tumors, metastases). Those who had been diagnosed would scarcely utter “I” and “breast cancer” in the same sentence. Women said little on the subject in part because they were not asked to. They were also fearful: A stubborn, long-standing conviction branded the ill personally responsible for what ailed them. (This is, of course, in part the subject of Sontag’s book.) The medical treatment then most common, the radical mastectomy, was disfiguring and, what’s more, seemed not to influence the outcome of a diagnosis. Death from the disease was reputed to be stealthy—and terrifying.

It was into this void, this vacant room, that women began to speak: first in the columns of women’s magazines (Ladies’ Home Journal, McCall’s, and Vogue), then in the headlines of national newspapers; first lady Betty Ford’s candor about her diagnosis and radical mastectomy, in 1974, made front-page news. Over time, the pronoun “I” would become essential, its invocation seemingly sure to lead to awareness, early detection, fewer women falling ill—and to fewer women acquiescing to life-altering, unnecessary surgeries. The logic, empowering and intoxicating, was soon formalized into charities and fundraising events, among the first of these the Susan G. Komen Breast Cancer Foundation’s inaugural Race for the Cure in Dallas in 1983.

More here.

Emily and I exchange techniques to stop crying. There comes a time, we say, when one is simply not in the mood. Pick a color, she tells me, and find every instance of it in the room. I pick blue. I pick dark green. One day I call her and say that if I start to cry I want her to squawk like a chicken. When my voice starts to shake she panics and quacks like a duck. Then I am laughing and crying all at once—wet and loud and thankful—and it feels as if my heart has turned itself inside out.

Emily and I exchange techniques to stop crying. There comes a time, we say, when one is simply not in the mood. Pick a color, she tells me, and find every instance of it in the room. I pick blue. I pick dark green. One day I call her and say that if I start to cry I want her to squawk like a chicken. When my voice starts to shake she panics and quacks like a duck. Then I am laughing and crying all at once—wet and loud and thankful—and it feels as if my heart has turned itself inside out.

In the same season that Human Flow was making the rounds of art house theaters in the United States, the great French Nouvelle Vague filmmaker Agnès Varda was collaborating with the artist JR on Faces Places (Visages, Villages). In the film, Varda and JR (like Weiwei, an installation artist) travel rural France meeting with waitresses, mailmen, miners, and factory workers, and photographing them in JR’s mobile photo booth. These portraits are then enlarged and pasted to the buildings that they work and live in—barns, abandoned homes, shipping containers—creating dramatic pop-up artworks.

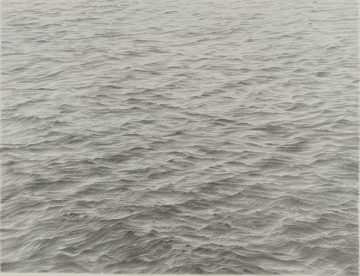

In the same season that Human Flow was making the rounds of art house theaters in the United States, the great French Nouvelle Vague filmmaker Agnès Varda was collaborating with the artist JR on Faces Places (Visages, Villages). In the film, Varda and JR (like Weiwei, an installation artist) travel rural France meeting with waitresses, mailmen, miners, and factory workers, and photographing them in JR’s mobile photo booth. These portraits are then enlarged and pasted to the buildings that they work and live in—barns, abandoned homes, shipping containers—creating dramatic pop-up artworks. Such work, mimetic in nature, necessitates an abandonment of the world. To scribe, to spend hours of one’s day, every day, copying the words of another artist or, as in Celmins’s practice, painstakingly copying the details of an object and, at the same time, attempting to remove all trace of one’s self, requires the artist to enter the object, and, in doing so, to leave the world. Akin to a small death, this practice is meditative in nature. In trauma, the mind leaves the body, dissociating, as a means to protect one’s psyche from the traumatic event. One antidote to this is to focus on one object: grounding one’s self in the present moment. Over the years, Celmins’s work has become more committed to the practice of fixing herself to the image. In this way, she folds herself into the work the same way the object she is copying is folded into the artwork. As Walter Benjamin writes in “On Copy,” “a copy can be understood as a memory.” Literally, when one makes a copy, one creates a memory of the original object. Indeed, Celmins’s art is deeply rooted in the work of memory: both the labor-intensive work of scribing, which presses the work being copied into the memory of scribe’s mind, and the act of copying, which results, as Benjamin writes, in a memory.

Such work, mimetic in nature, necessitates an abandonment of the world. To scribe, to spend hours of one’s day, every day, copying the words of another artist or, as in Celmins’s practice, painstakingly copying the details of an object and, at the same time, attempting to remove all trace of one’s self, requires the artist to enter the object, and, in doing so, to leave the world. Akin to a small death, this practice is meditative in nature. In trauma, the mind leaves the body, dissociating, as a means to protect one’s psyche from the traumatic event. One antidote to this is to focus on one object: grounding one’s self in the present moment. Over the years, Celmins’s work has become more committed to the practice of fixing herself to the image. In this way, she folds herself into the work the same way the object she is copying is folded into the artwork. As Walter Benjamin writes in “On Copy,” “a copy can be understood as a memory.” Literally, when one makes a copy, one creates a memory of the original object. Indeed, Celmins’s art is deeply rooted in the work of memory: both the labor-intensive work of scribing, which presses the work being copied into the memory of scribe’s mind, and the act of copying, which results, as Benjamin writes, in a memory. “I was diagnosed with breast cancer in 2014, at the age of forty-one,” the poet Anne Boyer writes early in her panoramic, book-length essay The Undying. Elemental and unadorned, the sentence does not leap out for quotation, and in the context of a review of some other essay, some other book, summary would be adequate (“At the age of forty-one, the poet Anne Boyer . . .”). But in a story about breast cancer, the voice of the speaker is consequential and Boyer makes this plain when, in consulting other women writers who suffered from the disease, she observes whether or not they have used the first person. Audre Lorde, for example, in The Cancer Journals (1980), her cancer memoir avant la lettre, has. Susan Sontag, who wrote Illness as Metaphor (1978) while being treated for the disease, has not. Boyer remarks on these choices not to find fault with them but to stress that decisions regarding whether and how to write about breast cancer are among its many agonies. The disease, she tells us, presents as “a disordering question of form.”

“I was diagnosed with breast cancer in 2014, at the age of forty-one,” the poet Anne Boyer writes early in her panoramic, book-length essay The Undying. Elemental and unadorned, the sentence does not leap out for quotation, and in the context of a review of some other essay, some other book, summary would be adequate (“At the age of forty-one, the poet Anne Boyer . . .”). But in a story about breast cancer, the voice of the speaker is consequential and Boyer makes this plain when, in consulting other women writers who suffered from the disease, she observes whether or not they have used the first person. Audre Lorde, for example, in The Cancer Journals (1980), her cancer memoir avant la lettre, has. Susan Sontag, who wrote Illness as Metaphor (1978) while being treated for the disease, has not. Boyer remarks on these choices not to find fault with them but to stress that decisions regarding whether and how to write about breast cancer are among its many agonies. The disease, she tells us, presents as “a disordering question of form.” Even if all the world agreed on the reality of anthropogenic global warming and on the gravity of the consequences for life on our planet, further difficult questions would arise. How are the needs of future generations to be balanced against the sufferings of people living today? How exactly are the potential perils of a seriously heated earth to be avoided? How are the burdens and costs to be distributed? How is the international cooperation required to be forged and sustained? As Evelyn Fox Keller and I argue in The Seasons Alter (2017), all these questions need to be posed, distinguished, and answered if the human population is to extricate itself from the mess some of its members have made (often unwittingly, though today in full consciousness).

Even if all the world agreed on the reality of anthropogenic global warming and on the gravity of the consequences for life on our planet, further difficult questions would arise. How are the needs of future generations to be balanced against the sufferings of people living today? How exactly are the potential perils of a seriously heated earth to be avoided? How are the burdens and costs to be distributed? How is the international cooperation required to be forged and sustained? As Evelyn Fox Keller and I argue in The Seasons Alter (2017), all these questions need to be posed, distinguished, and answered if the human population is to extricate itself from the mess some of its members have made (often unwittingly, though today in full consciousness). I watch bad movies, a pastime and a passion I have long shared with my father. When I was a child, we would sit on one of a series of couches scavenged from yard sales or curbsides, eating microwave popcorn while watching, say,

I watch bad movies, a pastime and a passion I have long shared with my father. When I was a child, we would sit on one of a series of couches scavenged from yard sales or curbsides, eating microwave popcorn while watching, say,  In 1882, linguists were electrified by the publication of a lost language—one supposedly spoken by the extinct Taensa people of Louisiana—because it bore hardly any relation to the languages of other Native American peoples of that region. The Taensa grammar was so unusual they were convinced it could teach them something momentous either about the region’s history, or the way that languages evolve, or both.

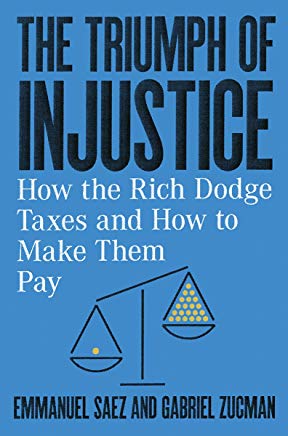

In 1882, linguists were electrified by the publication of a lost language—one supposedly spoken by the extinct Taensa people of Louisiana—because it bore hardly any relation to the languages of other Native American peoples of that region. The Taensa grammar was so unusual they were convinced it could teach them something momentous either about the region’s history, or the way that languages evolve, or both. The crowd at Elizabeth Warren’s rally in New York City in September was enthusiastic throughout, but it was her proposed new wealth tax—2 percent on wealth above $50 million, rising to 3 percent above $1 billion—that got them chanting: “Two cents! Two Cents! Two Cents!” Bernie Sanders has proposed a similar wealth tax, with rates peaking at 8 percent above $5 billion. In the October Democratic debate, a number of centrist candidates were open to it, and even Joe Biden, who seemed to reject one, argued for eliminating the favorable tax treatment of capital gains and raising income tax rates for the rich.

The crowd at Elizabeth Warren’s rally in New York City in September was enthusiastic throughout, but it was her proposed new wealth tax—2 percent on wealth above $50 million, rising to 3 percent above $1 billion—that got them chanting: “Two cents! Two Cents! Two Cents!” Bernie Sanders has proposed a similar wealth tax, with rates peaking at 8 percent above $5 billion. In the October Democratic debate, a number of centrist candidates were open to it, and even Joe Biden, who seemed to reject one, argued for eliminating the favorable tax treatment of capital gains and raising income tax rates for the rich. Many of us desperately want to preserve the thing we call nature or wilderness. But because we’ve destroyed so much, it is a slippery business to save what remains. If we don’t erect predator-proof fences, the world will lose the rabbit-eared bandicoot, a marsupial rodent with giant ears and a long pink nose. And we’ll lose the Newell’s shearwater, a seabird that brays like a donkey and dives down 150feet to catch squid. If we dobuild the fences, we lose the luxuriant creative abandon that produced these creatures. We create a demonstration plot of what once was.

Many of us desperately want to preserve the thing we call nature or wilderness. But because we’ve destroyed so much, it is a slippery business to save what remains. If we don’t erect predator-proof fences, the world will lose the rabbit-eared bandicoot, a marsupial rodent with giant ears and a long pink nose. And we’ll lose the Newell’s shearwater, a seabird that brays like a donkey and dives down 150feet to catch squid. If we dobuild the fences, we lose the luxuriant creative abandon that produced these creatures. We create a demonstration plot of what once was. Re-reading is often deemed comfort reading, and of course it can be. But books that are embedded in your history are rich in association, and picking them up often retriggers the emotions they provoked the first time, emotions allied to the feeling of being young. Comfort reading can be the most uncomfortable kind of all. I remember buying The Honourable Schoolboy at a bookshop in Newcastle that no longer exists; I remember taking it on a marathon coach journey, the length of the country; and I remember reading much of it in my first ever hammock in blistering sunshine – my first foreign holiday, not far from Nîmes. Similarly, it matters to me that my copy of Smiley’s People – a first edition given to me as a birthday gift – is identical to the one I borrowed from my local library in 1979 or 80. When I pick it up, I feel my younger self tugging at my sleeve, asking for his book back.

Re-reading is often deemed comfort reading, and of course it can be. But books that are embedded in your history are rich in association, and picking them up often retriggers the emotions they provoked the first time, emotions allied to the feeling of being young. Comfort reading can be the most uncomfortable kind of all. I remember buying The Honourable Schoolboy at a bookshop in Newcastle that no longer exists; I remember taking it on a marathon coach journey, the length of the country; and I remember reading much of it in my first ever hammock in blistering sunshine – my first foreign holiday, not far from Nîmes. Similarly, it matters to me that my copy of Smiley’s People – a first edition given to me as a birthday gift – is identical to the one I borrowed from my local library in 1979 or 80. When I pick it up, I feel my younger self tugging at my sleeve, asking for his book back.

I

I Preliminary research suggests that using CRISPR to treat cancer is safe in humans and could become a feasible therapeutic method in the future, although its efficacy is still unknown. Results from an ongoing clinical trial, led by hematologist Edward Stadtmauer of the University of Pennsylvania Perelman School of Medicine, will be presented at the American Society of Hematology meeting in December. The presentation abstract was published

Preliminary research suggests that using CRISPR to treat cancer is safe in humans and could become a feasible therapeutic method in the future, although its efficacy is still unknown. Results from an ongoing clinical trial, led by hematologist Edward Stadtmauer of the University of Pennsylvania Perelman School of Medicine, will be presented at the American Society of Hematology meeting in December. The presentation abstract was published  Once upon a time in Italy, a prominent citizen declared: “It is unacceptable that sometimes in certain parts of Milan there is such a presence of non-Italians that instead of thinking you are in an Italian or European city, you think you are in an African city.”

Once upon a time in Italy, a prominent citizen declared: “It is unacceptable that sometimes in certain parts of Milan there is such a presence of non-Italians that instead of thinking you are in an Italian or European city, you think you are in an African city.” The author of blueprint, Robert Plomin is an American psychologist, geneticist and neuroscientist and perhaps the most important voice, over many years, in the field of behavioral genetics. It is difficult today to imaging how scientifically taboo it was to study the genetics of human behavior after the racist horrors, bogus research and eugenics projects carried out by the Germans in the Nazi period. The field of behavioral genetics got off to a politically rocky beginning in the 1960s, but has gradually gained respectability, although some of its applications, particularly in the area of race, have been controversial (I would argue, misguided). The great achievement of the field is to show without any doubt that understanding human behavior must include the factor of genetic predispositions. Robert Plomin is to be admired for his contributions and his courage. What he writes deserves attention.

The author of blueprint, Robert Plomin is an American psychologist, geneticist and neuroscientist and perhaps the most important voice, over many years, in the field of behavioral genetics. It is difficult today to imaging how scientifically taboo it was to study the genetics of human behavior after the racist horrors, bogus research and eugenics projects carried out by the Germans in the Nazi period. The field of behavioral genetics got off to a politically rocky beginning in the 1960s, but has gradually gained respectability, although some of its applications, particularly in the area of race, have been controversial (I would argue, misguided). The great achievement of the field is to show without any doubt that understanding human behavior must include the factor of genetic predispositions. Robert Plomin is to be admired for his contributions and his courage. What he writes deserves attention. Is the deepening animosity between Democrats and Republicans based on genuine differences over policy and ideology or is it a form of tribal warfare rooted in an atavistic us-versus-them mentality?

Is the deepening animosity between Democrats and Republicans based on genuine differences over policy and ideology or is it a form of tribal warfare rooted in an atavistic us-versus-them mentality?

James Duesterberg at The Point:

Holloway invokes the story of Frankenstein’s monster, which is often taken as an allegory for capitalism. Frankenstein, a mad scientist who creates an artificial man, spends most of his story chasing after his invention or being chased by him; like a regulatory agency, the best he can do is damage control.

more here.