by Pranab Bardhan

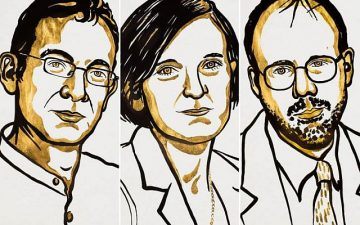

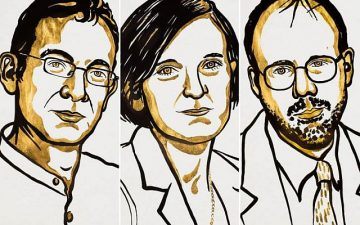

As a development economist I am celebrating, along with my co-professionals, the award of the Nobel Prize this year to three of our best development economists, Abhijit Banerjee, Esther Duflo and Michael Kremer. Even though the brilliance of these three economists has illuminated a whole range of subjects in our discipline, invariably, the write-ups in the media have referred to their great service to the cause of tackling global poverty, with their experimental approach, particularly the use of Randomized Control Trial (RCT).

As a development economist I am celebrating, along with my co-professionals, the award of the Nobel Prize this year to three of our best development economists, Abhijit Banerjee, Esther Duflo and Michael Kremer. Even though the brilliance of these three economists has illuminated a whole range of subjects in our discipline, invariably, the write-ups in the media have referred to their great service to the cause of tackling global poverty, with their experimental approach, particularly the use of Randomized Control Trial (RCT).

Of course, the Prize as such is not for great policy achievements in poverty reduction (if it were, the Chinese policy-makers enabling the lifting of nearly half a billion people above the poverty line in their country would have got prior attention), but for methodological breakthroughs, which the pioneering effort in extensive application of RCT in field experiments in several poor countries clearly is.

I should also proudly point out that these three economists did some of their major work while they were active members of a MacArthur Foundation-funded international research group on Inequality that I co-directed for more than 10 years starting in the mid-1990’s. Duflo was the youngest member of our group; incidentally, the French speakers (including, apart from Duflo, Thomas Piketty, Philippe Aghion, Roland Benabou, and Jean-Marie Baland) and the Bengalis (apart from myself, Abhijit Banerjee and Dilip Mookherjee) were together nearly half in strength in this group of about 18 members from different countries and social science disciplines.

The media write-ups on the Nobel Prize (including in leading magazines like The Economist), however, give a somewhat misleading impression about the evolution of thinking in development economics, as if after decades of pontification on structural transformation and prudential macro-economic policy and associated cross-country statistical exercises to understand the mainsprings of growth and development, the practitioners of RCT finally came along focusing our attention to the micro level, and providing us with a magic key, the so-called ‘gold standard’ in assessing poverty alleviation policies, telling us what ‘works’ at the ground level of policy intervention and what does not. Read more »

Kerschen’s depiction of the on-the-ground historical conditions that produced the Romantics’ most radical poetry—Shelley’s “Epipsychidion” and “The Masque of Anarchy,” Byron’s Don Juan—is a major achievement. But the book also offers an appealingly intimate view into Keats’s more mundane realities. The convalescent poet is forced to reckon with his debts, both financial and emotional: his life in Italy is dependent on his friends’ charity, and he is pressured to honor his engagement to Fanny Brawne, back in London. The author’s research is impeccable: the fictional Keats’s traits are all supported by what manuscript evidence tells us about the poet’s character. Even so, his choices often come as a pleasant surprise.

Kerschen’s depiction of the on-the-ground historical conditions that produced the Romantics’ most radical poetry—Shelley’s “Epipsychidion” and “The Masque of Anarchy,” Byron’s Don Juan—is a major achievement. But the book also offers an appealingly intimate view into Keats’s more mundane realities. The convalescent poet is forced to reckon with his debts, both financial and emotional: his life in Italy is dependent on his friends’ charity, and he is pressured to honor his engagement to Fanny Brawne, back in London. The author’s research is impeccable: the fictional Keats’s traits are all supported by what manuscript evidence tells us about the poet’s character. Even so, his choices often come as a pleasant surprise.

J

J Halfway through Sorry We Missed You, Ken Loach’s latest excursion into breadline Britain and a companion piece to his career-rejuvenating I, Daniel Blake, Abby (Debbie Honeywood) is recounting a nightmare in which she and her husband Ricky (Kris Hitchen) are stuck in quicksand. Their children, 11-year-old Lisa Jane (Katie Proctor) and 15-year-old Seb (Rhys Stone), try to pull them out but the more the adults struggle, the deeper they sink. There’s not much point in Abby mulling over the meaning of this, and no need to run it past a therapist. She and Ricky are workers in the gig economy, the instability of employment eating away at their wellbeing. “It’ll be different in six months,” is their plaintive mantra as they pile more hours on to their working week.

Halfway through Sorry We Missed You, Ken Loach’s latest excursion into breadline Britain and a companion piece to his career-rejuvenating I, Daniel Blake, Abby (Debbie Honeywood) is recounting a nightmare in which she and her husband Ricky (Kris Hitchen) are stuck in quicksand. Their children, 11-year-old Lisa Jane (Katie Proctor) and 15-year-old Seb (Rhys Stone), try to pull them out but the more the adults struggle, the deeper they sink. There’s not much point in Abby mulling over the meaning of this, and no need to run it past a therapist. She and Ricky are workers in the gig economy, the instability of employment eating away at their wellbeing. “It’ll be different in six months,” is their plaintive mantra as they pile more hours on to their working week. There’s no Wuthering Heights, no Moby-Dick, no Ulysses, but there is Half of a Yellow Sun, Bridget Jones’s Diary and Discworld: so announced the panel of experts assembled by the

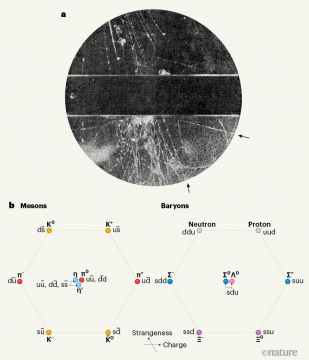

There’s no Wuthering Heights, no Moby-Dick, no Ulysses, but there is Half of a Yellow Sun, Bridget Jones’s Diary and Discworld: so announced the panel of experts assembled by the  In the late 1940s, the physicists George Rochester and Clifford Butler

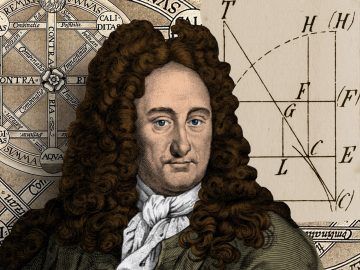

In the late 1940s, the physicists George Rochester and Clifford Butler In 1666, the German polymath

In 1666, the German polymath  The human brain contains roughly 85 billion neurons, wired together in an extraordinarily complex network of interconnected parts. It’s hardly surprising that we don’t understand the mind and how it works. But do we know enough about our experience of consciousness to suggest that consciousness cannot arise from nothing more than the physical interactions of bits of matter? Panpsychism is the idea that consciousness, or at least some mental aspect, is pervasive in the world, in atoms and rocks as well as in living creatures. Philosopher Philip Goff is one of the foremost modern advocates of this idea. We have a friendly and productive conversation, notwithstanding my own view that the laws of physics don’t need any augmenting to ultimately account for consciousness. If you’re not sympathetic toward panpsychism, this episode will at least help you understand why someone might be.

The human brain contains roughly 85 billion neurons, wired together in an extraordinarily complex network of interconnected parts. It’s hardly surprising that we don’t understand the mind and how it works. But do we know enough about our experience of consciousness to suggest that consciousness cannot arise from nothing more than the physical interactions of bits of matter? Panpsychism is the idea that consciousness, or at least some mental aspect, is pervasive in the world, in atoms and rocks as well as in living creatures. Philosopher Philip Goff is one of the foremost modern advocates of this idea. We have a friendly and productive conversation, notwithstanding my own view that the laws of physics don’t need any augmenting to ultimately account for consciousness. If you’re not sympathetic toward panpsychism, this episode will at least help you understand why someone might be.

Incarceration gave Hitler a chance to read more widely and gather his thoughts. One of his main preoccupations in Landsberg was the United States, which he was coming to regard as the model state and society, perhaps even more so than the British Empire. He “devoured” the memoirs of a returned German emigrant to the United States. “One should take America as a model,” he proclaimed.

Incarceration gave Hitler a chance to read more widely and gather his thoughts. One of his main preoccupations in Landsberg was the United States, which he was coming to regard as the model state and society, perhaps even more so than the British Empire. He “devoured” the memoirs of a returned German emigrant to the United States. “One should take America as a model,” he proclaimed. Thomas Mann’s reputation as a difficult, ponderous, heavyweight novelist, and the erudite allusions, serious subject matter, and philosophical themes of The Magic Mountain (1924) have led readers to ignore the comic and satiric tone that enlivens his morbid novel. His method is very different from the somber and solemn way most authors—like Tolstoy, Gide, and Solzhenitsyn—write about disease and death. Mann’s dark comedy, tinged with fear and disgust, takes place in the luxurious remote enclosed society of the International Sanatorium Berghof. He indicates the magic of the place with a witty game of recurring numbers. The young, naïve Hans Castorp, who leaves his ordinary life in Hamburg to visit his tubercular cousin Joachim Ziemssen, generates much of the comedy. Hans gradually progresses from incomprehension to knowledge and to eager acceptance of the distorted medical, social, and sexual customs on the magic mountain.

Thomas Mann’s reputation as a difficult, ponderous, heavyweight novelist, and the erudite allusions, serious subject matter, and philosophical themes of The Magic Mountain (1924) have led readers to ignore the comic and satiric tone that enlivens his morbid novel. His method is very different from the somber and solemn way most authors—like Tolstoy, Gide, and Solzhenitsyn—write about disease and death. Mann’s dark comedy, tinged with fear and disgust, takes place in the luxurious remote enclosed society of the International Sanatorium Berghof. He indicates the magic of the place with a witty game of recurring numbers. The young, naïve Hans Castorp, who leaves his ordinary life in Hamburg to visit his tubercular cousin Joachim Ziemssen, generates much of the comedy. Hans gradually progresses from incomprehension to knowledge and to eager acceptance of the distorted medical, social, and sexual customs on the magic mountain.

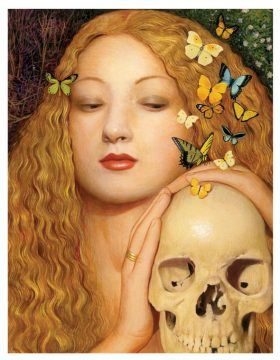

You will die, sooner or later. We all will. For everything that has a beginning has an end, an ineluctable consequence of the second law of thermodynamics. Few of us like to think about this troubling fact. But once birthed, the thought of oblivion can’t be completely erased. It lurks in the unconscious shadows, ready to burst forth. In my case, it was only as a mature man that I became fully mortal. I had wasted an entire evening playing an addictive, first-person shooter video game—running through subterranean halls, flooded corridors, nightmarishly turning tunnels, and empty plazas under a foreign sun, firing my weapons at hordes of aliens relentlessly pursuing me. I went to bed, easily falling asleep but awoke abruptly a few hours later. Abstract knowledge had turned to felt reality—I was going to die! Not right there and then but eventually.

You will die, sooner or later. We all will. For everything that has a beginning has an end, an ineluctable consequence of the second law of thermodynamics. Few of us like to think about this troubling fact. But once birthed, the thought of oblivion can’t be completely erased. It lurks in the unconscious shadows, ready to burst forth. In my case, it was only as a mature man that I became fully mortal. I had wasted an entire evening playing an addictive, first-person shooter video game—running through subterranean halls, flooded corridors, nightmarishly turning tunnels, and empty plazas under a foreign sun, firing my weapons at hordes of aliens relentlessly pursuing me. I went to bed, easily falling asleep but awoke abruptly a few hours later. Abstract knowledge had turned to felt reality—I was going to die! Not right there and then but eventually. As a development economist I am celebrating, along with my co-professionals, the award of the Nobel Prize this year to three of our best development economists, Abhijit Banerjee, Esther Duflo and Michael Kremer. Even though the brilliance of these three economists has illuminated a whole range of subjects in our discipline, invariably, the write-ups in the media have referred to their great service to the cause of tackling global poverty, with their experimental approach, particularly the use of Randomized Control Trial (RCT).

As a development economist I am celebrating, along with my co-professionals, the award of the Nobel Prize this year to three of our best development economists, Abhijit Banerjee, Esther Duflo and Michael Kremer. Even though the brilliance of these three economists has illuminated a whole range of subjects in our discipline, invariably, the write-ups in the media have referred to their great service to the cause of tackling global poverty, with their experimental approach, particularly the use of Randomized Control Trial (RCT).

When I was a young attending surgeon on the faculty in the Division of Cardiothoracic Surgery, one of the things I got frequently called for was management of malignant pleural or pericardial effusions. Once a patient develops malignant pleural or pericardial effusion the median survival is only two months, so I would do things that would relieve the acute symptoms and perhaps try to prevent fluid from reaccumulating, but nothing drastic or major. One evening in late October, one of the nurses who had known me called to say that her father was being treated for lung cancer but had to be admitted with a large pleural effusion and that she and her father’s Oncologist would like me to manage it. I met the fine 72-year old retired banker, and while he was short of breath even as he talked, he was in a very upbeat mood. I decided to insert a chest tube to drain the pleural fluid and relieve his symptoms. As I was doing the procedure at the bedside the patient mentioned to me that his oncologist has assured him that once his fluid is out he will start him on a new regimen of chemotherapy and he should expect to live for a few more years. I was disturbed to hear the false hope he was being given.

When I was a young attending surgeon on the faculty in the Division of Cardiothoracic Surgery, one of the things I got frequently called for was management of malignant pleural or pericardial effusions. Once a patient develops malignant pleural or pericardial effusion the median survival is only two months, so I would do things that would relieve the acute symptoms and perhaps try to prevent fluid from reaccumulating, but nothing drastic or major. One evening in late October, one of the nurses who had known me called to say that her father was being treated for lung cancer but had to be admitted with a large pleural effusion and that she and her father’s Oncologist would like me to manage it. I met the fine 72-year old retired banker, and while he was short of breath even as he talked, he was in a very upbeat mood. I decided to insert a chest tube to drain the pleural fluid and relieve his symptoms. As I was doing the procedure at the bedside the patient mentioned to me that his oncologist has assured him that once his fluid is out he will start him on a new regimen of chemotherapy and he should expect to live for a few more years. I was disturbed to hear the false hope he was being given. These energetic lines open Moon and Sun: Rumi’s Rubaiyat, Zara Houshmand’s brilliant translation of selected ruba’iyat – quatrains – by Molana Jalaluddin Rumi, and set the tone for an inspiring and exhilarating sojourn through the passions of the peerless Sage of Konya.

These energetic lines open Moon and Sun: Rumi’s Rubaiyat, Zara Houshmand’s brilliant translation of selected ruba’iyat – quatrains – by Molana Jalaluddin Rumi, and set the tone for an inspiring and exhilarating sojourn through the passions of the peerless Sage of Konya.