Gareth Williams in MIL:

In September 1798 a self-published book with an outlandish premise was about to change the world. At first sight, “An Inquiry into the Cowpox” looked more like a piece of vanity publishing than one of the greatest landmarks in the history of medicine. Its author, a doctor called Edward Jenner, was largely unknown outside rural Gloucestershire. In a 75-page illustrated manual, Jenner explained how people could protect themselves from smallpox – a horrific brute of a disease that killed one person in 12 and left many survivors scarred for life – by inoculating themselves with cowpox, an obscure disease that affected cattle. This extraordinary process was to be known as vaccination, from the Latin for cow.

In September 1798 a self-published book with an outlandish premise was about to change the world. At first sight, “An Inquiry into the Cowpox” looked more like a piece of vanity publishing than one of the greatest landmarks in the history of medicine. Its author, a doctor called Edward Jenner, was largely unknown outside rural Gloucestershire. In a 75-page illustrated manual, Jenner explained how people could protect themselves from smallpox – a horrific brute of a disease that killed one person in 12 and left many survivors scarred for life – by inoculating themselves with cowpox, an obscure disease that affected cattle. This extraordinary process was to be known as vaccination, from the Latin for cow.

The “Inquiry” was an instant sensation. Within a few years, vaccination became mainstream medical practice in Britain, Europe and North America, while the King of Spain sent it as a “divine gift” to all the Spanish colonies. By the time Jenner died in 1823, millions had come to regard him as a hero. His admirers included Native Americans, the Empress of Russia (who sent him a diamond ring out of gratitude), and Napoleon, who “could refuse this man nothing” even though France and England were at war. In 1881 Louis Pasteur proposed that the term “vaccination” should be used for any kind of inoculation.

But not everyone thought Jenner was a saint. In 1858 Prince Albert unveiled a statue to Jenner in Trafalgar Square, amid much pomp and circumstance. There was such an outcry that two years later the statue was carted away to a lower-key resting place in Kensington Gardens. Jenner’s earliest and most vocal opponents had been men of the church, who reasoned that smallpox was a God-given fact of life and death. If the Almighty had decided that someone would be smitten by smallpox, then any attempt to subvert this divine intention was blasphemy.

More here.

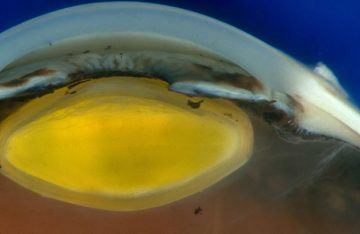

A Japanese woman in her forties has become the first person in the world to have her cornea repaired using reprogrammed stem cells. At a press conference on 29 August, ophthalmologist Kohji Nishida from Osaka University, Japan, said the woman has a disease in which the stem cells that repair the cornea, a transparent layer that covers and protects the eye, are lost. The condition makes vision blurry and can lead to blindness.

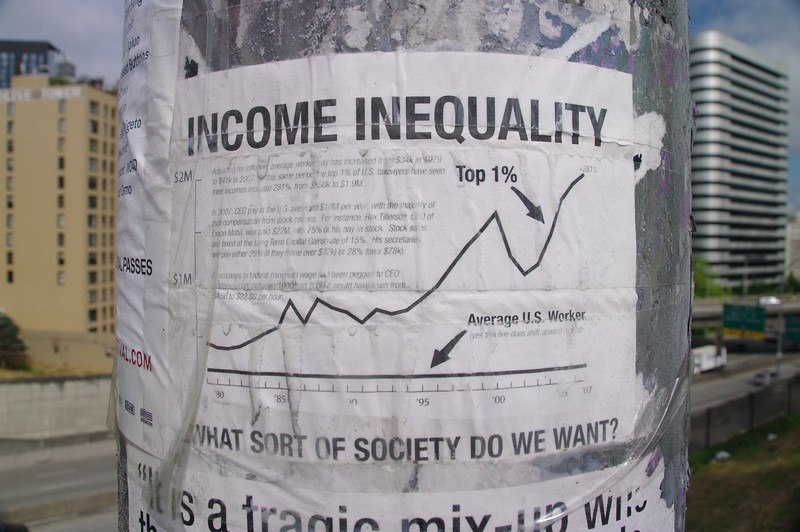

A Japanese woman in her forties has become the first person in the world to have her cornea repaired using reprogrammed stem cells. At a press conference on 29 August, ophthalmologist Kohji Nishida from Osaka University, Japan, said the woman has a disease in which the stem cells that repair the cornea, a transparent layer that covers and protects the eye, are lost. The condition makes vision blurry and can lead to blindness. There is widespread concern about increasing or high economic inequality in many countries, both rich and poor. At a global level, according to the World Inequality Report 2018, the richest 1% in the world reaped 27% of the growth in world income between 1980 and 2016, while bottom 50% of the population got only 12%. Over roughly the same period, however, absolute poverty by standard measures has generally been on the decline in most countries. By the widely-used World Bank estimates, in 2015 only about 10 per cent of the world population lived below its common, admittedly rather austere, poverty line of $1.90 per capita per day (at 2011 purchasing power parity), compared to 36 per cent in 1990. This decline is by and large valid even if one uses broader measures of poverty that take into account some non-income indicators (like deprivations in health and education) for the countries for which such data are available.

There is widespread concern about increasing or high economic inequality in many countries, both rich and poor. At a global level, according to the World Inequality Report 2018, the richest 1% in the world reaped 27% of the growth in world income between 1980 and 2016, while bottom 50% of the population got only 12%. Over roughly the same period, however, absolute poverty by standard measures has generally been on the decline in most countries. By the widely-used World Bank estimates, in 2015 only about 10 per cent of the world population lived below its common, admittedly rather austere, poverty line of $1.90 per capita per day (at 2011 purchasing power parity), compared to 36 per cent in 1990. This decline is by and large valid even if one uses broader measures of poverty that take into account some non-income indicators (like deprivations in health and education) for the countries for which such data are available.

For me, a highlight of an otherwise ill-spent youth was reading mathematician John Casti’s fantastic book “

For me, a highlight of an otherwise ill-spent youth was reading mathematician John Casti’s fantastic book “ Have you ever been in this situation where you had to get a group of 3 men and their sisters across a river, but the boat only held two and you had to take precautions to ensure the women got across without being assaulted?

Have you ever been in this situation where you had to get a group of 3 men and their sisters across a river, but the boat only held two and you had to take precautions to ensure the women got across without being assaulted?

Last weekend, a bat got into my house somehow. I first heard it in the small hours of Friday night as it scratched around somewhere near the furnace flue. I didn’t know if it was an animal settling into a new home in my attic, or if perhaps it was going out periodically to get food and bringing it back to feed babies in an established nest. All became clear very late the next night, when the bat managed to get out of the enclosure around the flue and then exit the closet where the furnace is. After some drama that I need not recount here, it flew out the front door, and I stopped gibbering on my front walk and went back inside.

Last weekend, a bat got into my house somehow. I first heard it in the small hours of Friday night as it scratched around somewhere near the furnace flue. I didn’t know if it was an animal settling into a new home in my attic, or if perhaps it was going out periodically to get food and bringing it back to feed babies in an established nest. All became clear very late the next night, when the bat managed to get out of the enclosure around the flue and then exit the closet where the furnace is. After some drama that I need not recount here, it flew out the front door, and I stopped gibbering on my front walk and went back inside. Trapped

Trapped

It is hard work to write a book, so there is unavoidable irony in fashioning a volume on the value of being idle. There is a paradox, too: to praise idleness is to suggest that there is some point to it, that wasting time is not a waste of time. Paradox infuses the experience of being idle. Rapturous relaxation can be difficult to distinguish from melancholy. When the academic year comes to an end, I find myself sprawled on the couch, re-watching old episodes of British comedy panel shows on a loop. I cannot tell if I am depressed or taking an indulgent break. As Samuel Johnson wrote: “Every man is, or hopes to be, an Idler.” As he also wrote: “There are … miseries in idleness, which the Idler only can conceive.”

It is hard work to write a book, so there is unavoidable irony in fashioning a volume on the value of being idle. There is a paradox, too: to praise idleness is to suggest that there is some point to it, that wasting time is not a waste of time. Paradox infuses the experience of being idle. Rapturous relaxation can be difficult to distinguish from melancholy. When the academic year comes to an end, I find myself sprawled on the couch, re-watching old episodes of British comedy panel shows on a loop. I cannot tell if I am depressed or taking an indulgent break. As Samuel Johnson wrote: “Every man is, or hopes to be, an Idler.” As he also wrote: “There are … miseries in idleness, which the Idler only can conceive.” “The so-called ‘female’ brain,” says Rippon, “has suffered centuries of being described as undersized, underdeveloped, evolutionarily inferior, poorly organised and generally defective.” Such assertions were, and still are, so widespread that Rippon admits feeling as though she’s playing “Whac-a-Mole”. She has barely disproved the newest study professing to demonstrate how men and women’s brains differ, when another is published.

“The so-called ‘female’ brain,” says Rippon, “has suffered centuries of being described as undersized, underdeveloped, evolutionarily inferior, poorly organised and generally defective.” Such assertions were, and still are, so widespread that Rippon admits feeling as though she’s playing “Whac-a-Mole”. She has barely disproved the newest study professing to demonstrate how men and women’s brains differ, when another is published.