From Phys.Org:

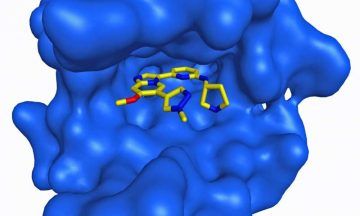

Scientists from the National Institutes of Health and Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center have devised a potential treatment against a common type of leukemia that could have implications for many other types of cancer. The new approach takes aim at a way that cancer cells evade the effects of drugs, a process called adaptive resistance. The researchers, in a range of studies, identified a cellular pathway that allows a form of acute myeloid leukemia (AML), a deadly blood and bone marrow cancer, to elude the activity of a promising class of drugs. They then engineered a compound that appears to launch a two-pronged attack against the cancer. In several experiments, the compound blocked a mutant protein that causes the AML. At the same time, it halted the cancer cells‘ ability to sidestep the compound’s effects. The results, reported Sept. 4 in Science Translational Medicine, could lead to the development of new therapies against AML and cancers that act in similar ways.

Scientists from the National Institutes of Health and Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center have devised a potential treatment against a common type of leukemia that could have implications for many other types of cancer. The new approach takes aim at a way that cancer cells evade the effects of drugs, a process called adaptive resistance. The researchers, in a range of studies, identified a cellular pathway that allows a form of acute myeloid leukemia (AML), a deadly blood and bone marrow cancer, to elude the activity of a promising class of drugs. They then engineered a compound that appears to launch a two-pronged attack against the cancer. In several experiments, the compound blocked a mutant protein that causes the AML. At the same time, it halted the cancer cells‘ ability to sidestep the compound’s effects. The results, reported Sept. 4 in Science Translational Medicine, could lead to the development of new therapies against AML and cancers that act in similar ways.

Co-corresponding authors Daniel Starczynowski, Ph.D., at Cincinnati Children’s, Craig Thomas, Ph.D., at NIH’s National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (NCATS) and their colleagues wanted to better understand drug resistance in a form of AML caused by a mutant protein called FLT3. This form of AML accounts for roughly 25% of all newly diagnosed AML cases, and patients often have a poor prognosis. A more thorough understanding of the drug resistance process could help them find ways to improve therapy options. FLT3 belongs to a class of enzymes called kinases. Kinases are proteins that play a role in cell growth and proliferation. When kinases work overtime, they can cause some cancers. Drugs that block kinase activity have been effective in treating cancers. While many of these drugs work initially, often in combination with other therapies, cancer cells frequently find ways to bypass the drugs’ effects and begin growing again. For many patients, this drug resistance can be deadly. FLT3 is always turned on in these cancer cells, sending chemical signals for the cells to grow and divide. Scientists have designed drugs to block FLT3 activity, but the AML cells eventually find ways to get the growth signals elsewhere.

More here.

Mario Seccareccia and Marc Lavoie over at INET:

Mario Seccareccia and Marc Lavoie over at INET:

The people of Jammu and Kashmir on both sides of the border have been continuously betrayed by the governments of Pakistan and India.

The people of Jammu and Kashmir on both sides of the border have been continuously betrayed by the governments of Pakistan and India. Last night I was talking with our mutual friend S, and she said, “I always wanted to hear what Ann would say. She would listen to others present arguments, and then, when it was her turn to speak, she would find the beautiful bits in what she’d heard and put it all back together in a way that was brilliant and original and made people think she was extending their ideas.”

Last night I was talking with our mutual friend S, and she said, “I always wanted to hear what Ann would say. She would listen to others present arguments, and then, when it was her turn to speak, she would find the beautiful bits in what she’d heard and put it all back together in a way that was brilliant and original and made people think she was extending their ideas.”

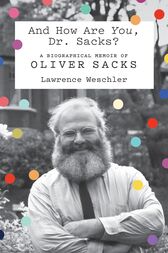

Written by one brilliant writer about another, this remarkable book is, in part, about the craft of writing. But in the main, it’s an account of author Lawrence Weschler’s friendship with Oliver Sacks, a man whom he describes as “impressively erudite and impossibly cuddly.” Sacks comes across as singular. For many years, he lived by himself on City Island, not far from Manhattan, in a house he acquired when he swam out there, saw a house he liked, learned that it was for sale, and bought it that afternoon, his wet trunks dripping in the real estate agent’s office. He regularly swam for miles in the ocean, sometimes late at night. He loved cuttlefish and motorcycles, which he rode, drug-fueled, up and down the California coast when he was a neurology resident at UCLA. A friend of his from that time recalled, “Oliver wouldn’t behave, he wouldn’t follow rules, he’d eat the leftover food off the patients’ trays during rounds, and he drove them nuts.”

Written by one brilliant writer about another, this remarkable book is, in part, about the craft of writing. But in the main, it’s an account of author Lawrence Weschler’s friendship with Oliver Sacks, a man whom he describes as “impressively erudite and impossibly cuddly.” Sacks comes across as singular. For many years, he lived by himself on City Island, not far from Manhattan, in a house he acquired when he swam out there, saw a house he liked, learned that it was for sale, and bought it that afternoon, his wet trunks dripping in the real estate agent’s office. He regularly swam for miles in the ocean, sometimes late at night. He loved cuttlefish and motorcycles, which he rode, drug-fueled, up and down the California coast when he was a neurology resident at UCLA. A friend of his from that time recalled, “Oliver wouldn’t behave, he wouldn’t follow rules, he’d eat the leftover food off the patients’ trays during rounds, and he drove them nuts.” Brexit

Brexit A

A In 1906, Dutch writer Maarten Maartens—acclaimed in his lifetime but now mostly forgotten—published a surreal, satirical novel called The Healers. The book centers on one Professor Lisse, who has conjured up a potential bioweapon: the Semicolon Bacillus, an “especial variety of the Comma.” The doctor has killed hundreds of rabbits demonstrating the Semicolon’s toxicity, but, at the beginning of the novel, he hasn’t yet succeeded in getting his punctuation past the human immune system, which destroys Semicolons instantly as soon as they enter the mouth.

In 1906, Dutch writer Maarten Maartens—acclaimed in his lifetime but now mostly forgotten—published a surreal, satirical novel called The Healers. The book centers on one Professor Lisse, who has conjured up a potential bioweapon: the Semicolon Bacillus, an “especial variety of the Comma.” The doctor has killed hundreds of rabbits demonstrating the Semicolon’s toxicity, but, at the beginning of the novel, he hasn’t yet succeeded in getting his punctuation past the human immune system, which destroys Semicolons instantly as soon as they enter the mouth. Physicists study systems that are sufficiently simple that it’s possible to find deep unifying principles applicable to all situations. In psychology or sociology that’s a lot harder. But as I say at the end of this episode, Mindscape is a safe space for grand theories of everything. Psychologist Michele Gelfand claims that there’s a single dimension that captures a lot about how cultures differ: a spectrum between “tight” and “loose,” referring to the extent to which social norms are automatically respected. Oregon is loose; Alabama is tight. Italy is loose; Singapore is tight. It’s a provocative thesis, back up by copious amounts of data, that could shed light on human behavior not only in different parts of the world, but in different settings at work or at school.

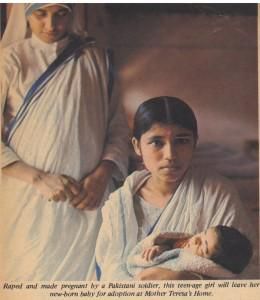

Physicists study systems that are sufficiently simple that it’s possible to find deep unifying principles applicable to all situations. In psychology or sociology that’s a lot harder. But as I say at the end of this episode, Mindscape is a safe space for grand theories of everything. Psychologist Michele Gelfand claims that there’s a single dimension that captures a lot about how cultures differ: a spectrum between “tight” and “loose,” referring to the extent to which social norms are automatically respected. Oregon is loose; Alabama is tight. Italy is loose; Singapore is tight. It’s a provocative thesis, back up by copious amounts of data, that could shed light on human behavior not only in different parts of the world, but in different settings at work or at school. The post- Liberation War generation of Bangladesh know stories from 1971 all too well. Our families are framed and bound by the history of this war. What Bangladeshi family has not been touched by the passion, famine, murders and blood that gave birth to a new nation as it seceded from Pakistan? Bangladesh was one of the only successful nationalist movements post-

The post- Liberation War generation of Bangladesh know stories from 1971 all too well. Our families are framed and bound by the history of this war. What Bangladeshi family has not been touched by the passion, famine, murders and blood that gave birth to a new nation as it seceded from Pakistan? Bangladesh was one of the only successful nationalist movements post- C

C IT BEGINS THE WAY

IT BEGINS THE WAY A

A