Elizabeth Chatterjee in the LRB:

Elizabeth Chatterjee in the LRB:

A few minutes before 22 people were murdered in a Walmart in El Paso on 3 August, in a now-familiar ritual of American gun violence, a manifesto was uploaded to the fringe online forum 8chan (tagline: ‘Embrace infamy’). For the most part, the four-page screed parroted standard white supremacist themes, warning of a ‘Hispanic invasion’ while fretting that the 8chan community might find its contents a little ‘meh’. Yet the manifesto’s title, ‘The Inconvenient Truth’, suggested a second fixation. Its opening lines praised the lengthy statement published on the same forum five months earlier by the New Zealand mosque attacker – a self-proclaimed ‘eco-fascist’ – and it name-checked an unexpected source: Dr Seuss’s 1971 environmentalist children’s fable The Lorax.

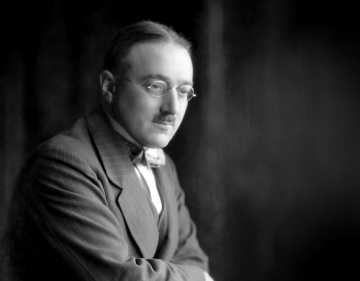

The link between environmentalism and racism isn’t new. Romantic advocates of pristine ‘wilderness’ often sought to exclude poor and native populations. Madison Grant, who helped to found the Bronx Zoo, Glacier National Park and the Save the Redwoods League, was also the author of the eugenicist tract The Passing of the Great Race (1916). Hitler called the book his ‘bible’. A green wing of the Nazi movement saw vegetarianism, organic farming and nature worship as the natural corollary of the party’s racial obsessions. Oswald Mosley’s British Union of Fascists advocated a return to the land. After the war, the BUF’s agrarian adviser, Jorian Jenks, was one of the founders of the Soil Association.

More here.

Clive Cookson in the FT:

Clive Cookson in the FT: In the 20th century an unfortunate gulf opened up in philosophy between the “continental” and “analytic” schools. Even if you’ve never studied the subject, you might well have heard of this one split. But as the British moral philosopher Bernard Williams once pointed out, the very characterisation of this gulf is odd—one school being characterised by its qualities, the other geographically, like dividing cars between four-wheel drive models and those made in Japan.

In the 20th century an unfortunate gulf opened up in philosophy between the “continental” and “analytic” schools. Even if you’ve never studied the subject, you might well have heard of this one split. But as the British moral philosopher Bernard Williams once pointed out, the very characterisation of this gulf is odd—one school being characterised by its qualities, the other geographically, like dividing cars between four-wheel drive models and those made in Japan.

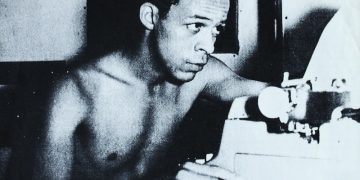

Charles Wright refused to audition as a hatchet man contestant in the Manhattan token wars in which only one Black writer is left standing during a given era. When I asked George Schuyler, author of the classic novel Black No More, why he, at the time, hadn’t received more recognition, he said he wasn’t a member of The Clique. Tokenism deprives readers of access to a variety of Black writers and smothers the efforts of individual geniuses like Elizabeth Nunez, J. J. Phillips, Charles Wright, and William Demby, whose final novel, King Comus, I published.

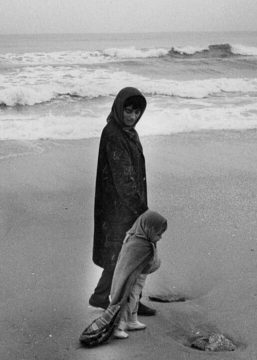

Charles Wright refused to audition as a hatchet man contestant in the Manhattan token wars in which only one Black writer is left standing during a given era. When I asked George Schuyler, author of the classic novel Black No More, why he, at the time, hadn’t received more recognition, he said he wasn’t a member of The Clique. Tokenism deprives readers of access to a variety of Black writers and smothers the efforts of individual geniuses like Elizabeth Nunez, J. J. Phillips, Charles Wright, and William Demby, whose final novel, King Comus, I published. One of the most wonderful things about Varda and her camera was the way she circled back, again and again, to previous sites and subjects of her films. Among others, she maintained bonds with the fishermen of La pointe courte, in 2008 performing an anniversary tribute to honor their part in the film. She captured the scene in The Beaches of Agnès, and mutual gratitude hangs in the salt air. Around Demy’s 1990 death from AIDS, Varda not only filmed his childhood memories; she also returned to Rochefort with the cast of a film Demy shot there, making The Young Girls Turn 25 to honor The Young Girls of Rochefort. Through her returns, Varda gave these stories rich new layers. The reciprocal vulnerability between the artist and her subjects extends to viewers when, at the end of Faces Places, we see our bowl cut-rocking cat lady auteur weep in disappointment when Godard isn’t home to receive the pastries she brought him. When has a visionary drawn us in this close?

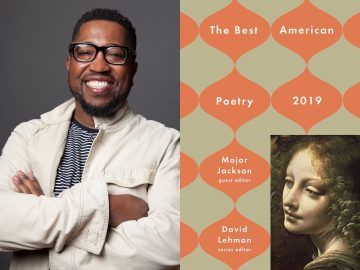

One of the most wonderful things about Varda and her camera was the way she circled back, again and again, to previous sites and subjects of her films. Among others, she maintained bonds with the fishermen of La pointe courte, in 2008 performing an anniversary tribute to honor their part in the film. She captured the scene in The Beaches of Agnès, and mutual gratitude hangs in the salt air. Around Demy’s 1990 death from AIDS, Varda not only filmed his childhood memories; she also returned to Rochefort with the cast of a film Demy shot there, making The Young Girls Turn 25 to honor The Young Girls of Rochefort. Through her returns, Varda gave these stories rich new layers. The reciprocal vulnerability between the artist and her subjects extends to viewers when, at the end of Faces Places, we see our bowl cut-rocking cat lady auteur weep in disappointment when Godard isn’t home to receive the pastries she brought him. When has a visionary drawn us in this close? Poems have reacquainted me with the spectacular spirit of the human, that which is fundamentally elusive to algorithms, artificial intelligence, behavioral science, and genetic research: “Sometimes I get up early and even my soul is wet” (Pablo Neruda, “Here I Love You”); “Earth’s the right place for love: / I don’t know where it’s likely to go better” (Robert Frost, “Birches”); “I wonder what death tastes like. / Sometimes I toss the butterflies / Back into the air” (Yusef Komunyakaa, “Venus’s Flytrap”); “The world / is flux, and light becomes what it touches” (Lisel Mueller, “Monet Refuses the Operation”); “We do not want them to have less. / But it is only natural that we should think we have not enough” (Gwendolyn Brooks, “Beverly Hills, Chicago”). Once, while in graduate school, reading Wordsworth’s “Ode: Intimations of Immortality from Recollections of Early Childhood” in the corner of a café, I was surprised to find myself with brimming eyes, filled with unspeakable wonder and sadness at the veracity of his words: “Our birth is but a sleep and a forgetting: / The Soul that rises with us, our life’s Star, / Hath had elsewhere its setting, / And cometh from afar.” Poetry, as the poet Edward Hirsch has written, “speaks out of a solitude to a solitude.”

Poems have reacquainted me with the spectacular spirit of the human, that which is fundamentally elusive to algorithms, artificial intelligence, behavioral science, and genetic research: “Sometimes I get up early and even my soul is wet” (Pablo Neruda, “Here I Love You”); “Earth’s the right place for love: / I don’t know where it’s likely to go better” (Robert Frost, “Birches”); “I wonder what death tastes like. / Sometimes I toss the butterflies / Back into the air” (Yusef Komunyakaa, “Venus’s Flytrap”); “The world / is flux, and light becomes what it touches” (Lisel Mueller, “Monet Refuses the Operation”); “We do not want them to have less. / But it is only natural that we should think we have not enough” (Gwendolyn Brooks, “Beverly Hills, Chicago”). Once, while in graduate school, reading Wordsworth’s “Ode: Intimations of Immortality from Recollections of Early Childhood” in the corner of a café, I was surprised to find myself with brimming eyes, filled with unspeakable wonder and sadness at the veracity of his words: “Our birth is but a sleep and a forgetting: / The Soul that rises with us, our life’s Star, / Hath had elsewhere its setting, / And cometh from afar.” Poetry, as the poet Edward Hirsch has written, “speaks out of a solitude to a solitude.” The climate of South Asia is not kind to ancient DNA. It is hot and it rains. In monsoon season, water seeps into ancient bones in the ground, degrading the old genetic material. So by the time archeologists and geneticists finally got DNA out of a tiny ear bone from a 4,000-plus-year-old skeleton, they had already tried dozens of samples—all from cemeteries of the mysterious Indus Valley civilization, all without any success. The Indus Valley civilization, also known as the Harappan civilization, flourished 4,000 years ago in what is now India and Pakistan. It surpassed its contemporaries, Mesopotamia and ancient Egypt, in size. Its trade routes stretched thousands of miles. It had agriculture and planned cities and sewage systems. And then, it disappeared. “The Indus Valley civilization has been an enigma for South Asians. We read about it in our textbooks,” says

The climate of South Asia is not kind to ancient DNA. It is hot and it rains. In monsoon season, water seeps into ancient bones in the ground, degrading the old genetic material. So by the time archeologists and geneticists finally got DNA out of a tiny ear bone from a 4,000-plus-year-old skeleton, they had already tried dozens of samples—all from cemeteries of the mysterious Indus Valley civilization, all without any success. The Indus Valley civilization, also known as the Harappan civilization, flourished 4,000 years ago in what is now India and Pakistan. It surpassed its contemporaries, Mesopotamia and ancient Egypt, in size. Its trade routes stretched thousands of miles. It had agriculture and planned cities and sewage systems. And then, it disappeared. “The Indus Valley civilization has been an enigma for South Asians. We read about it in our textbooks,” says  Over the past two centuries, millions of dedicated people – revolutionaries, activists, politicians, and theorists – have yet to curb the disastrous and increasingly globalised trajectory of economic polarisation and ecological degradation. Perhaps because we are utterly trapped in flawed ways of thinking about technology and economy – as the current discourse on climate change shows. Rising greenhouse gas emissions are not just generating climate change. They are giving more and more of us climate anxiety –

Over the past two centuries, millions of dedicated people – revolutionaries, activists, politicians, and theorists – have yet to curb the disastrous and increasingly globalised trajectory of economic polarisation and ecological degradation. Perhaps because we are utterly trapped in flawed ways of thinking about technology and economy – as the current discourse on climate change shows. Rising greenhouse gas emissions are not just generating climate change. They are giving more and more of us climate anxiety –

“Correlation is not causation.”

“Correlation is not causation.”

In the early 1950s, a young economist named Paul Volcker worked as a human calculator in an office deep inside the Federal Reserve Bank of New York. He crunched numbers for the people who made decisions, and he told his wife that he saw little chance of ever moving up. The central bank’s leadership included bankers, lawyers and an Iowa hog farmer, but not a single economist. The Fed’s chairman, a former stockbroker named William McChesney Martin, once told a visitor that he kept a small staff of economists in the basement of the Fed’s Washington headquarters. They were in the building, he said, because they asked good questions. They were in the basement because “they don’t know their own limitations.”

In the early 1950s, a young economist named Paul Volcker worked as a human calculator in an office deep inside the Federal Reserve Bank of New York. He crunched numbers for the people who made decisions, and he told his wife that he saw little chance of ever moving up. The central bank’s leadership included bankers, lawyers and an Iowa hog farmer, but not a single economist. The Fed’s chairman, a former stockbroker named William McChesney Martin, once told a visitor that he kept a small staff of economists in the basement of the Fed’s Washington headquarters. They were in the building, he said, because they asked good questions. They were in the basement because “they don’t know their own limitations.” To read Käsebier Takes Berlin today, more than 80 years after its original publication, is to experience occasional shocks of recognition. Many have noted the similarities between Weimar-era Germany and the Trump-era United States, and in Käsebier, these parallels sometimes come to the fore. As Duvernoy notes in her introduction, the rise of Käsebier is, in effect, the result of a story gone viral. In one passage, we come across the phrase “fake news.” In another, Miermann expresses something similar to the news fatigue so many Americans feel: “I’m always supposed to get worked up: against sales taxes, for sales taxes, against excise taxes, for excise taxes. I’m not going to get worked up again until five o’clock tomorrow unless a beautiful girl walks into the room!”

To read Käsebier Takes Berlin today, more than 80 years after its original publication, is to experience occasional shocks of recognition. Many have noted the similarities between Weimar-era Germany and the Trump-era United States, and in Käsebier, these parallels sometimes come to the fore. As Duvernoy notes in her introduction, the rise of Käsebier is, in effect, the result of a story gone viral. In one passage, we come across the phrase “fake news.” In another, Miermann expresses something similar to the news fatigue so many Americans feel: “I’m always supposed to get worked up: against sales taxes, for sales taxes, against excise taxes, for excise taxes. I’m not going to get worked up again until five o’clock tomorrow unless a beautiful girl walks into the room!” Baths are very comforting: gentler, calmer than showers. The slow clean. For a while, though, across a patch of nervous books in the mid-twentieth century, baths were troublesome. They were prone to intrusion and disorder. They were too hot, too small, too crowded with litanies of junk: newspapers, cigarettes, alcohol, razors.

Baths are very comforting: gentler, calmer than showers. The slow clean. For a while, though, across a patch of nervous books in the mid-twentieth century, baths were troublesome. They were prone to intrusion and disorder. They were too hot, too small, too crowded with litanies of junk: newspapers, cigarettes, alcohol, razors. The great service done by Mitchell Zuckoff in Fall and Rise is to document in minute but telling detail the innumerable human tragedies that unfolded in the space of a few hours on the morning of 11 September 2001.

The great service done by Mitchell Zuckoff in Fall and Rise is to document in minute but telling detail the innumerable human tragedies that unfolded in the space of a few hours on the morning of 11 September 2001. In November 1959 aged 26,

In November 1959 aged 26,