by Ashutosh Jogalekar

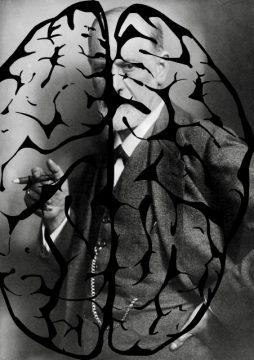

Mathematics and music have a pristine, otherworldly beauty that is very unlike that found in other human endeavors. Both of them seem to exhibit an internal structure, a unique concatenation of qualities that lives in a world of their own, independent of their creators. But mathematics might be so completely unique in this regard that its practitioners have seriously questioned whether mathematical facts, axioms and theorems may not simply exist on their own, simply waiting to be discovered rather than invented. Arthur Rubinstein and Andre Previn’s performance of Chopin’s second piano concerto sends unadulterated jolts of pleasure through my mind every time I listen to it, but I don’t for a moment doubt that those notes would not exist were it not for the existence of Chopin, Rubinstein and Previn. I am not sure I could say the same about Euler’s beautiful identity connecting three of the most fundamental constants in math and nature – e, pi and i. That succinct arrangement of symbols seems to simply be, waiting for Euler to chance upon it, the way a constellation of stars has waited for billions of years for an astronomer to find it.

The beauty of music and mathematics is that anyone can catch a glimpse of this timelessness of ideas, and even someone untrained in these fields can appreciate the basics. The most shattering intellectual moment of my life was when, in my last year of high school, I read in George Gamow’s “One, Two, Three, Infinity” about the fact that different infinities can actually be compared. Until then the whole concept of infinity had been a single concept to me, like the color red. The question of whether one infinity could be “larger” than another sounded as preposterous to me as whether one kind of red was better than another. But here was the story of an entire superstructure of infinities which could be compared, studied and taken apart, and whose very existence raised one of the most famous, and still unsolved, problems in math – the Continuum Hypothesis. The day I read about this fact in Gamow’s book, something changed in my mind; I got the feeling that some small combination of neuronal gears permanently shifted, altering forever a part of my perspective on the world. Read more »

Fans are the people who know the quotes, the dates of publication, the batting averages, the bassist on this album, the team that general manager coached before. I am not a fan. Don’t get me wrong. I’m full of enthusiasms. But I can’t match you statistic for statistic. I haven’t read the major author’s minor novel. I don’t care who the bassist was. You win. I’m an amateur.

Fans are the people who know the quotes, the dates of publication, the batting averages, the bassist on this album, the team that general manager coached before. I am not a fan. Don’t get me wrong. I’m full of enthusiasms. But I can’t match you statistic for statistic. I haven’t read the major author’s minor novel. I don’t care who the bassist was. You win. I’m an amateur. When I watched the 2019 documentary on Apollo 11, it carried me back not to the summer of 1969, when it happened, but to the mid-1980s, when I was an undergrad. I was eight when Apollo 11 launched; of course I was aware of the space program and the moon landings, but I don’t have any memories of everyone gathering around to watch those first steps on another world. My parents weren’t particularly interested, and I don’t remember being caught by the spirit of the times myself.

When I watched the 2019 documentary on Apollo 11, it carried me back not to the summer of 1969, when it happened, but to the mid-1980s, when I was an undergrad. I was eight when Apollo 11 launched; of course I was aware of the space program and the moon landings, but I don’t have any memories of everyone gathering around to watch those first steps on another world. My parents weren’t particularly interested, and I don’t remember being caught by the spirit of the times myself. cinematic representations of Muslims. Stage One features stereotyped figures (the taxi driver, terrorist, cornershop owner, or oppressed woman). Stage Two involves a portrayal that subverts and challenges those stereotypes. Finally, Stage Three is ‘the Promised Land, where you play a character whose story is not intrinsically linked to his race’. Does

cinematic representations of Muslims. Stage One features stereotyped figures (the taxi driver, terrorist, cornershop owner, or oppressed woman). Stage Two involves a portrayal that subverts and challenges those stereotypes. Finally, Stage Three is ‘the Promised Land, where you play a character whose story is not intrinsically linked to his race’. Does

Our expectations sculpt neural activity, causing our brains to represent the outcomes of our actions as we expect them to unfold. This is consistent with a growing psychological literature suggesting that our experience of our actions is biased towards what we expect. —

Our expectations sculpt neural activity, causing our brains to represent the outcomes of our actions as we expect them to unfold. This is consistent with a growing psychological literature suggesting that our experience of our actions is biased towards what we expect. — Into the Woods

Into the Woods

My friend does not use punctuation when he texts, so there is a stream-of-consciousness quality to much of his communications. According to the fine folks at

My friend does not use punctuation when he texts, so there is a stream-of-consciousness quality to much of his communications. According to the fine folks at  “A lie is a lie is a lie,” Whoopi Goldberg said. It was May 2nd, and she was on the set of “The View,” the daytime talk show that she co-hosts. The subject was Attorney General

“A lie is a lie is a lie,” Whoopi Goldberg said. It was May 2nd, and she was on the set of “The View,” the daytime talk show that she co-hosts. The subject was Attorney General  My colleague Patrick Riley from Google has a

My colleague Patrick Riley from Google has a  One night in May, a strange and seemingly inexplicable thing happened in India. A divisive and ineffectual prime minister returned to power with a historic mandate.

One night in May, a strange and seemingly inexplicable thing happened in India. A divisive and ineffectual prime minister returned to power with a historic mandate. The Cannes Film Festival has been an adoring showcase for Quentin Tarantino ever since he was anointed with the big prize, the Palme d’Or, for Pulp Fiction in 1994. That only made the discomfort of his tense exchange with

The Cannes Film Festival has been an adoring showcase for Quentin Tarantino ever since he was anointed with the big prize, the Palme d’Or, for Pulp Fiction in 1994. That only made the discomfort of his tense exchange with  It took me three tries to understand even a little of Mrs. Dalloway, Virginia Woolf’s famous 1925 modernist novel set on a single day in London. Even now, when I try to explain the book, I tend to sound like a stereotypical rambling undergraduate literary analyst, parroting lecture slides and pontificating on the meaning of life — if Good Will Hunting saw me at a bar, he’d take me outside. But confusing as it is, this is a book that makes me walk around differently. Here’s why:

It took me three tries to understand even a little of Mrs. Dalloway, Virginia Woolf’s famous 1925 modernist novel set on a single day in London. Even now, when I try to explain the book, I tend to sound like a stereotypical rambling undergraduate literary analyst, parroting lecture slides and pontificating on the meaning of life — if Good Will Hunting saw me at a bar, he’d take me outside. But confusing as it is, this is a book that makes me walk around differently. Here’s why: