Jenann Ismael at the TLS:

Some claim that the idea of human freedom is built on illusions about human specialness that are a holdover from a religious conception of the world, and that they should be swept aside with the advancing tides of science. This position has been trumpeted loudly by people who present themselves as brave defenders of science: by scientists such as Einstein, Stephen Hawking and Richard Dawkins, and by philosophers including Alexander Rosenberg and Sam Harris. To most people, however, it seems literally unbelievable that the scales of fate don’t hang in the balance when making a difficult decision. And it is not just those dark nights of the soul where this matters. You think that you could cross the street here or there, pick these socks or those, go to bed at a reasonable hour or stay up, howl at the moon and eat donuts till dawn. Every choice is a juncture in history and it is up to you to determine which way to go.

Some claim that the idea of human freedom is built on illusions about human specialness that are a holdover from a religious conception of the world, and that they should be swept aside with the advancing tides of science. This position has been trumpeted loudly by people who present themselves as brave defenders of science: by scientists such as Einstein, Stephen Hawking and Richard Dawkins, and by philosophers including Alexander Rosenberg and Sam Harris. To most people, however, it seems literally unbelievable that the scales of fate don’t hang in the balance when making a difficult decision. And it is not just those dark nights of the soul where this matters. You think that you could cross the street here or there, pick these socks or those, go to bed at a reasonable hour or stay up, howl at the moon and eat donuts till dawn. Every choice is a juncture in history and it is up to you to determine which way to go.

Yet, if there is one foundational scientific fact, it is that things can’t happen that the laws of physics don’t allow. And the clash between these two things shows that there is something centrally important about ourselves and our position in the cosmos that we don’t understand.

more here.

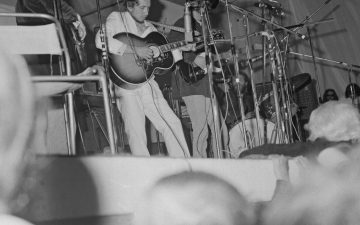

Fifty years ago this month, Bob Dylan played the Isle of Wight Festival. They say if you can remember 1969 you weren’t there, but I do and I was, boomerphobes. I can even tell you what half a century feels like if you’re interested, although it’s a bit layered. A bit contradictory.

Fifty years ago this month, Bob Dylan played the Isle of Wight Festival. They say if you can remember 1969 you weren’t there, but I do and I was, boomerphobes. I can even tell you what half a century feels like if you’re interested, although it’s a bit layered. A bit contradictory. It’s hard to overstate the significance of

It’s hard to overstate the significance of  On an October morning in 2006, a young man backed his truck into the driveway of a one-room schoolhouse. He walked into the school and after ordering the boy students, the teacher and a few other adults to leave, he lined up 10 girls, ages 9 to 13, and shot them. The mindless horror of that attack drew intense and sustained press as well as, later on, books and film. Although there had been two other school shootings only a few days earlier, what made this massacre especially notable was the fact that its landscape was an Amish community — notoriously peaceful and therefore the most unlikely venue for such violence.

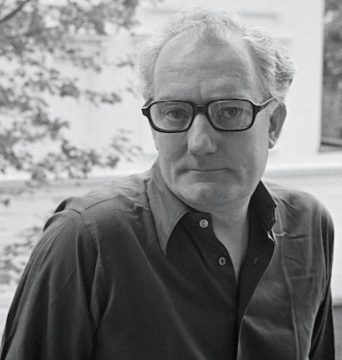

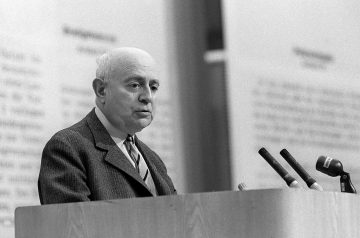

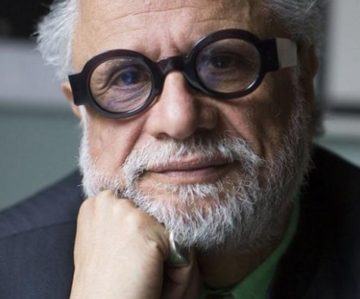

On an October morning in 2006, a young man backed his truck into the driveway of a one-room schoolhouse. He walked into the school and after ordering the boy students, the teacher and a few other adults to leave, he lined up 10 girls, ages 9 to 13, and shot them. The mindless horror of that attack drew intense and sustained press as well as, later on, books and film. Although there had been two other school shootings only a few days earlier, what made this massacre especially notable was the fact that its landscape was an Amish community — notoriously peaceful and therefore the most unlikely venue for such violence. When I met him, Bryan Magee was nearly 89, marvellously lucid, curious to hear about my time at Oxford, and paralysed from the waist down: in many ways the ideal interviewee. For a generation of young viewers, Magee’s legendary television series about philosophy were a baptism in the waters of the subject, and he the urbane and worldly gatekeeper to a realm of theoretic abstraction and grounded, vigorous discussion such as had never before been entered—a watershed moment in a primetime slot.

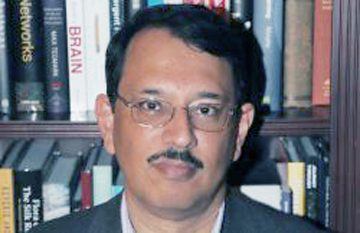

When I met him, Bryan Magee was nearly 89, marvellously lucid, curious to hear about my time at Oxford, and paralysed from the waist down: in many ways the ideal interviewee. For a generation of young viewers, Magee’s legendary television series about philosophy were a baptism in the waters of the subject, and he the urbane and worldly gatekeeper to a realm of theoretic abstraction and grounded, vigorous discussion such as had never before been entered—a watershed moment in a primetime slot. India’s decision two days ago to revoke most of Article 370 of its constitution and annex the part of Jammu & Kashmir it holds has sent Subcontinental and transcontinental punditocracy into a frenzy of analysis, interpretation, speculation, and prediction. Several scenarios have risen to the surface.

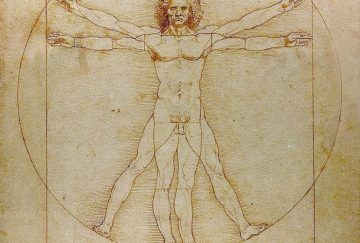

India’s decision two days ago to revoke most of Article 370 of its constitution and annex the part of Jammu & Kashmir it holds has sent Subcontinental and transcontinental punditocracy into a frenzy of analysis, interpretation, speculation, and prediction. Several scenarios have risen to the surface. In recent years, biology’s “nature vs. nurture” war has reemerged with advanced weapons, although the central questions have not changed: What makes us human? Why are we different from one another? Nonetheless, the methods used to address them have undergone several revolutions. We now benefit from hundreds of twin and adoption studies, which have provided heritability estimates for dozens of characteristics relating to human behavior and wellness. Simultaneously, we are reaping the benefits of technological breakthroughs that have made it possible to screen thousands of individuals to uncover genes associated with particular traits. Thanks to this, we have been able to correlate genetic signatures with a growing list of physical (e.g., height, skin color), physiological (e.g., risk for type-2 diabetes, hypertension), and behavioral (e.g., risk for depression, autism) traits. At the same time, epidemiology, psychology, and sociology continue to demonstrate the pliability of the human experience across populations, and we continue to learn more about the social forces that create vast differences in the human experience.

In recent years, biology’s “nature vs. nurture” war has reemerged with advanced weapons, although the central questions have not changed: What makes us human? Why are we different from one another? Nonetheless, the methods used to address them have undergone several revolutions. We now benefit from hundreds of twin and adoption studies, which have provided heritability estimates for dozens of characteristics relating to human behavior and wellness. Simultaneously, we are reaping the benefits of technological breakthroughs that have made it possible to screen thousands of individuals to uncover genes associated with particular traits. Thanks to this, we have been able to correlate genetic signatures with a growing list of physical (e.g., height, skin color), physiological (e.g., risk for type-2 diabetes, hypertension), and behavioral (e.g., risk for depression, autism) traits. At the same time, epidemiology, psychology, and sociology continue to demonstrate the pliability of the human experience across populations, and we continue to learn more about the social forces that create vast differences in the human experience. We’ve got these bodies and these brains, which work okay, but we also have minds. We see, we hear, we think, we feel, we plan, we act, we do; we’re conscious. Viewed from the outside, you see a reasonably finely tuned mechanism. From the inside, we all experience ourselves as having a mind, as feeling, thinking, experiencing, being, which is pretty central to our conception of ourselves. It also raises any number of philosophical and scientific problems. When it comes to explaining the objective stuff from the outside—the behavior and so on—you put together some neural and computational mechanisms, and we have a paradigm for explaining those.

We’ve got these bodies and these brains, which work okay, but we also have minds. We see, we hear, we think, we feel, we plan, we act, we do; we’re conscious. Viewed from the outside, you see a reasonably finely tuned mechanism. From the inside, we all experience ourselves as having a mind, as feeling, thinking, experiencing, being, which is pretty central to our conception of ourselves. It also raises any number of philosophical and scientific problems. When it comes to explaining the objective stuff from the outside—the behavior and so on—you put together some neural and computational mechanisms, and we have a paradigm for explaining those.

“I claim the right to the United States, for myself and my children and my uncles and cousins, by manifest destiny.” The claimant is Suketu Mehta, in This Land Is Our Land: An Immigrant’s Manifesto. The reference to manifest destiny isn’t merely trolling. Mehta’s thesis is that extensive migration from poor parts of the globe to the US is as inevitable and justified as the westward migration that built this country. He goes on:

“I claim the right to the United States, for myself and my children and my uncles and cousins, by manifest destiny.” The claimant is Suketu Mehta, in This Land Is Our Land: An Immigrant’s Manifesto. The reference to manifest destiny isn’t merely trolling. Mehta’s thesis is that extensive migration from poor parts of the globe to the US is as inevitable and justified as the westward migration that built this country. He goes on: When we design a skyscraper we expect it will perform to specification: that the tower will support so much weight and be able to withstand an earthquake of a certain strength.

When we design a skyscraper we expect it will perform to specification: that the tower will support so much weight and be able to withstand an earthquake of a certain strength. The cheerleaders for Prime Minister Narendra Modi of India are cheering for Partition redux, a world-class massacre, ethnic cleansing. The brute power of Hindu supremacy has its own logic, and it requires not only that Kashmiris be denied a future but also that they be humiliated and punished for their past sin of not being grateful Indians. While individual Indian Muslims across the country are being lynched for trading beef or

The cheerleaders for Prime Minister Narendra Modi of India are cheering for Partition redux, a world-class massacre, ethnic cleansing. The brute power of Hindu supremacy has its own logic, and it requires not only that Kashmiris be denied a future but also that they be humiliated and punished for their past sin of not being grateful Indians. While individual Indian Muslims across the country are being lynched for trading beef or  The authors find little proof of increasing busyness among the population. Yes, as expected, people were spending far more time on digital devices in 2015 than they were in 2000. But the data provides little evidence that people now spend more time multitasking or that they’re switching more often from one activity to another, which might make our time seem fragmented and frantic.

The authors find little proof of increasing busyness among the population. Yes, as expected, people were spending far more time on digital devices in 2015 than they were in 2000. But the data provides little evidence that people now spend more time multitasking or that they’re switching more often from one activity to another, which might make our time seem fragmented and frantic.

In novels spanning several hundred years of history, Toni Morrison used her historical imagination and her remarkable gifts of language to chronicle the horrors of slavery and Jim Crow, and their continuing fallout on the everyday lives of black Americans. Violent, heart-wrenching events occur in her fiction: a runaway slave named Sethe cuts the throat of her baby daughter with a handsaw to spare her the fate she suffered herself as a slave (

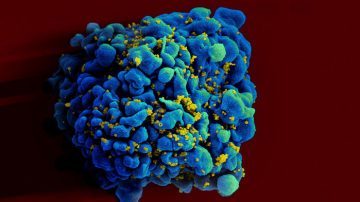

In novels spanning several hundred years of history, Toni Morrison used her historical imagination and her remarkable gifts of language to chronicle the horrors of slavery and Jim Crow, and their continuing fallout on the everyday lives of black Americans. Violent, heart-wrenching events occur in her fiction: a runaway slave named Sethe cuts the throat of her baby daughter with a handsaw to spare her the fate she suffered herself as a slave ( Drugs work stunningly well to control HIV—but not in everyone, and not without side effects. That’s why a small cadre of patients known as elite controllers has long fascinated researchers: Their immune system alone naturally suppresses HIV for decades without drugs. Now one team, inspired by success in mice, hopes to endow HIV-infected people with tailormade immune cells that target HIV, in effect creating elite controllers in the clinic. The immune strategy has risks, but it builds on increasingly popular cancer treatments with T cells engineered to have surface proteins, called chimeric antigen receptors (CARs), that can recognize markers on the surfaces of tumor cells and destroy the cancer. Such CAR T cells can also be tailored to identify and eliminate HIV-infected cells. This approach was tested in HIV-infected humans long before CAR T cells proved their worth against cancer, but it roundly failed. The field wants “to move what’s been learned from cancer back to HIV, completing the circle,” says Steven Deeks, an HIV/AIDS clinician at the University of California, San Francisco, who first tested a CAR T cell against the virus in the late 1990s.

Drugs work stunningly well to control HIV—but not in everyone, and not without side effects. That’s why a small cadre of patients known as elite controllers has long fascinated researchers: Their immune system alone naturally suppresses HIV for decades without drugs. Now one team, inspired by success in mice, hopes to endow HIV-infected people with tailormade immune cells that target HIV, in effect creating elite controllers in the clinic. The immune strategy has risks, but it builds on increasingly popular cancer treatments with T cells engineered to have surface proteins, called chimeric antigen receptors (CARs), that can recognize markers on the surfaces of tumor cells and destroy the cancer. Such CAR T cells can also be tailored to identify and eliminate HIV-infected cells. This approach was tested in HIV-infected humans long before CAR T cells proved their worth against cancer, but it roundly failed. The field wants “to move what’s been learned from cancer back to HIV, completing the circle,” says Steven Deeks, an HIV/AIDS clinician at the University of California, San Francisco, who first tested a CAR T cell against the virus in the late 1990s. I think it’s very difficult to make the case for an objective morality if you’re using the word ‘objective’ in a strong sense, either to mean a universal morality or a foundational morality that all people everywhere understand and accept in a globalising world.

I think it’s very difficult to make the case for an objective morality if you’re using the word ‘objective’ in a strong sense, either to mean a universal morality or a foundational morality that all people everywhere understand and accept in a globalising world.