Emma Taggart in My Modern Met:

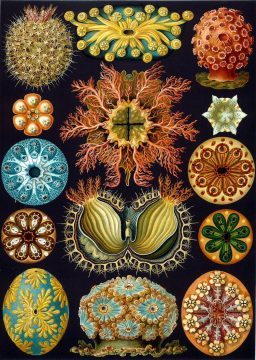

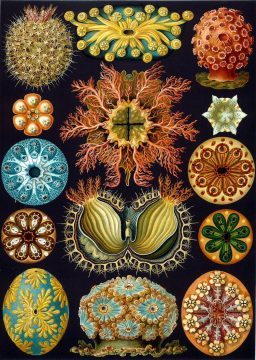

Today, many science books are full of detailed photos that reveal the intricate parts of plant life, but prior to the invention of photography (and macro photography), it was up to botanical illustrators and researchers to record the fascinating forms of flora and fauna. One scientist who recorded his findings with drawings is Ernst Heinrich Haeckel, a German biologist, naturalist, philosopher, and physician.

Today, many science books are full of detailed photos that reveal the intricate parts of plant life, but prior to the invention of photography (and macro photography), it was up to botanical illustrators and researchers to record the fascinating forms of flora and fauna. One scientist who recorded his findings with drawings is Ernst Heinrich Haeckel, a German biologist, naturalist, philosopher, and physician.

Made during the late 19th and early 20th centuries, his brilliantly colorful and highly stylized drawings, watercolors, and sketches reveal how different forms of plant life appear under the microscope. Although each hand-drawn organism looks like something from a science fiction book, Haeckel’s body of work sheds light on the incredible hidden intricacies of real, natural forms that inhabit the Earth.

Born in Germany in 1834, Ernst Haeckel studied medicine at the University of Berlin and graduated in 1857. While he was a student, his professor Johannes Müller, took him on a summer field trip to observe small sea creatures off the coast of Heligoland in the North Sea, sparking his life-long fascination for natural forms and biology. In 1859, when Haeckel was 25, he traveled to Italy where he spent time in Napoli discovering his artistic talent. In the same year, he went to Messina where he studied the structures of radiolarians (microscopic protozoa that produce intricate mineral skeletons). He published 59 scientific illustrations between 1860 and 1862, along with the original microscope slides.

More here. (Note: Thanks to dear friend Bim Bissel)

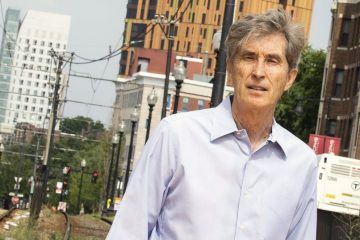

Fiction shines a light on the human condition by putting people into imaginary situations and envisioning what might happen. Science fiction expands this technique by considering situations in the future, with advanced technology, or with utterly different social contexts. Seth MacFarlane’s show The Orville is good old-fashioned space opera, but it’s also a laboratory for exploring the intricacies of human behavior. There are interpersonal conflicts, sexual politics, alien perspectives, and grappling with the implications of technology. I talk with Seth about all these issues, and maybe a little bit about whether it’s a good idea to block people on Twitter.

Fiction shines a light on the human condition by putting people into imaginary situations and envisioning what might happen. Science fiction expands this technique by considering situations in the future, with advanced technology, or with utterly different social contexts. Seth MacFarlane’s show The Orville is good old-fashioned space opera, but it’s also a laboratory for exploring the intricacies of human behavior. There are interpersonal conflicts, sexual politics, alien perspectives, and grappling with the implications of technology. I talk with Seth about all these issues, and maybe a little bit about whether it’s a good idea to block people on Twitter.

The mass shootings over the weekend in El Paso, Texas, and Dayton, Ohio, killed at least 31 people and wounded scores more. Those incidents were just the latest such deadly attacks in the United States, which has tallied more than 250 since Jan. 1, according to a new report by

The mass shootings over the weekend in El Paso, Texas, and Dayton, Ohio, killed at least 31 people and wounded scores more. Those incidents were just the latest such deadly attacks in the United States, which has tallied more than 250 since Jan. 1, according to a new report by  But there is a catch. This groundbreaking research is relevant

But there is a catch. This groundbreaking research is relevant  F

F Today, many science books are full of detailed photos that reveal the intricate parts of plant life, but prior to the invention of photography (and macro photography), it was up to

Today, many science books are full of detailed photos that reveal the intricate parts of plant life, but prior to the invention of photography (and macro photography), it was up to  During the three years that Billy Budd took shape, Britten and Forster occasionally disagreed about just how brazen the piece should be. In one instance, Forster complained that one of Claggart’s arias was just not hot-blooded enough. “I want passion—love constricted, perverted, poisoned, but nevertheless flowing down its agonising channel; a sexual discharge gone evil,” Forster wrote. “Not soggy depression or growling remorse.” Britten—who had largely been circumspect about his own homosexuality, publicly avoiding the subject of his long relationship with the tenor Peter Pears—strongly disagreed, and as a consequence, a rift opened up between librettist and composer, the one a daring idealist, the other a more cautious realist.

During the three years that Billy Budd took shape, Britten and Forster occasionally disagreed about just how brazen the piece should be. In one instance, Forster complained that one of Claggart’s arias was just not hot-blooded enough. “I want passion—love constricted, perverted, poisoned, but nevertheless flowing down its agonising channel; a sexual discharge gone evil,” Forster wrote. “Not soggy depression or growling remorse.” Britten—who had largely been circumspect about his own homosexuality, publicly avoiding the subject of his long relationship with the tenor Peter Pears—strongly disagreed, and as a consequence, a rift opened up between librettist and composer, the one a daring idealist, the other a more cautious realist. This past April, Mount Sinai oncologist

This past April, Mount Sinai oncologist

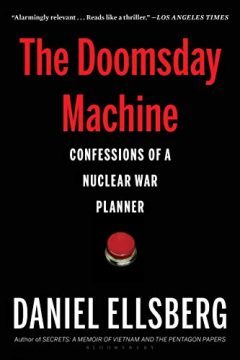

DANIEL ELLSBERG

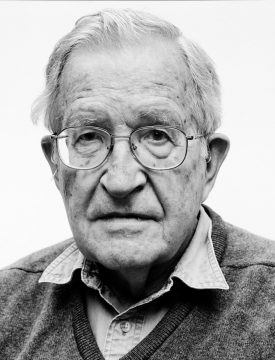

DANIEL ELLSBERG Noam Chomsky: Trump’s diatribes successfully inflame his audience, many of whom apparently feel deeply threatened by diversity, cultural change, or simply the recognition that the White Christian nation of their collective imagination is changing before their eyes. White supremacy is nothing new in the U.S. The late George Frederickson’s

Noam Chomsky: Trump’s diatribes successfully inflame his audience, many of whom apparently feel deeply threatened by diversity, cultural change, or simply the recognition that the White Christian nation of their collective imagination is changing before their eyes. White supremacy is nothing new in the U.S. The late George Frederickson’s  Born in an Ohio steel town in the depths of the Great Depression, Morrison carved out a literary home for the voices of African Americans, first as an acclaimed editor and then with novels such as The Bluest Eye,

Born in an Ohio steel town in the depths of the Great Depression, Morrison carved out a literary home for the voices of African Americans, first as an acclaimed editor and then with novels such as The Bluest Eye,  ‘We have already exited the state of environmental conditions that allowed the human animal to evolve in the first place,’ Wallace-Wells writes, ‘in an unsure and unplanned bet on just what that animal can endure. The climate system that raised us, and raised everything we now know as human civilisation, is now, like a parent, dead.’ He is not a climate scientist, so is perhaps less circumspect than he might be: the data here is designed to scare us. ‘I am alarmed,’ he writes. Who isn’t? We know exactly where we are, despite the continuous chatter of doubt and denial. Wallace-Wells is scathing about the oil industry, whose disinformation clogs public discourse and waylays political processes: ‘A more grotesque performance of corporate evilness is hardly imaginable, and, a generation from now, oil-backed denial will likely be seen as among the most heinous conspiracies against human health and well-being as have been perpetrated in the modern world.’

‘We have already exited the state of environmental conditions that allowed the human animal to evolve in the first place,’ Wallace-Wells writes, ‘in an unsure and unplanned bet on just what that animal can endure. The climate system that raised us, and raised everything we now know as human civilisation, is now, like a parent, dead.’ He is not a climate scientist, so is perhaps less circumspect than he might be: the data here is designed to scare us. ‘I am alarmed,’ he writes. Who isn’t? We know exactly where we are, despite the continuous chatter of doubt and denial. Wallace-Wells is scathing about the oil industry, whose disinformation clogs public discourse and waylays political processes: ‘A more grotesque performance of corporate evilness is hardly imaginable, and, a generation from now, oil-backed denial will likely be seen as among the most heinous conspiracies against human health and well-being as have been perpetrated in the modern world.’ The laughter of Morrison’s characters disguises pain, deprivation and violation. It is laughter at a series of bad, cruel jokes. The real joke in naming Sula’s neighbourhood “The Bottom”, when it perches on barren Ohio uplands is that, in many senses it really is “the bottom” after all. Nothing is what it seems; no appearance, no relationship, can be trusted to endure.

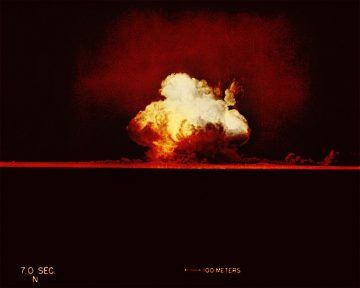

The laughter of Morrison’s characters disguises pain, deprivation and violation. It is laughter at a series of bad, cruel jokes. The real joke in naming Sula’s neighbourhood “The Bottom”, when it perches on barren Ohio uplands is that, in many senses it really is “the bottom” after all. Nothing is what it seems; no appearance, no relationship, can be trusted to endure. Crawford Lake is so small it takes just 10 minutes to stroll all the way around its shore. But beneath its surface, this pond in southern Ontario in Canada hides something special that is attracting attention from scientists around the globe. They are in search of a distinctive marker buried deep in the mud — a signal designating the moment when humans achieved such power that they started irreversibly transforming the planet. The mud layers in this lake could be ground zero for the Anthropocene — a potential new epoch of geological time.

Crawford Lake is so small it takes just 10 minutes to stroll all the way around its shore. But beneath its surface, this pond in southern Ontario in Canada hides something special that is attracting attention from scientists around the globe. They are in search of a distinctive marker buried deep in the mud — a signal designating the moment when humans achieved such power that they started irreversibly transforming the planet. The mud layers in this lake could be ground zero for the Anthropocene — a potential new epoch of geological time. Calls for a Manhattan Project–style crash effort to develop artificial intelligence (AI) technology are thick on the ground these days. Oren Etzioni, the CEO of the Allen Institute for Artificial Intelligence, recently issued such a call on

Calls for a Manhattan Project–style crash effort to develop artificial intelligence (AI) technology are thick on the ground these days. Oren Etzioni, the CEO of the Allen Institute for Artificial Intelligence, recently issued such a call on