Alpine meadow near my house in July, 2019.

Month: August 2019

Either You Don’t Know Anything or Most of What You Believe is True

by Tim Sommers

Unfortunately, you have a brain tumor. You don’t know it yet. Your doctor doesn’t know it yet. But you are beginning to have symptoms. The tumor is pressing on surrounding brain tissue and causing you develop a number of delusional beliefs. You believe you are the best swimmer in the world. You believe that dogs and cats are aliens. You believe that you invented the apostrophe. You also, as it happens, believe that you have a brain tumor.

Unfortunately, you have a brain tumor. You don’t know it yet. Your doctor doesn’t know it yet. But you are beginning to have symptoms. The tumor is pressing on surrounding brain tissue and causing you develop a number of delusional beliefs. You believe you are the best swimmer in the world. You believe that dogs and cats are aliens. You believe that you invented the apostrophe. You also, as it happens, believe that you have a brain tumor.

So, you have a brain tumor. You believe you have a brain tumor. And the cause of your believing that you have a brain tumor is the brain tumor that you have. So, when the doctor diagnosis you with a brain tumor, are you entitled to say, “I know, right!”?

If the belief that you have a brain tumor is caused by the same thing that causes you to believe you invented the apostrophe, I think most of us would say that you don’t, in fact, know that you have a brain tumor – even if you believe it and it’s true. But it’s difficult to see why. It has something to do, probably, with justification.

Implicitly or explicitly philosophers, epistemologists to be more specific, define knowledge as justified true belief. Knowledge, then, is a kind of belief. What kind? Well, of course, the belief has to be true to count as knowledge. But it also has to be justified. If you correctly guess what the weather will be like tomorrow, we shouldn’t say that you knew it. If you predict the weather accurately using instruments and satellite maps, then you may have had or have knowledge. The brain tumor example raises questions about how justification works. There’s something wrong with the connection the belief has to why you believe it. It echoes an even more famous puzzle – the Gettier problem. Read more »

Jerusalem through the Door of God’s Friend

by Shadab Zeest Hashmi

“Taxi to Bethlehem, taxi to Jericho!” the man at a tourism kiosk is shouting, as I make my way from the tram to Jaffa Gate, known also as Hebron Gate, to Muslims as “Bab al Khalil,” or “door of the friend,” named after Hebron where the prophet Ibrahim/Abraham (Khalil al Allah “God’s Friend”) is laid to rest. Of significance too, is the association of this gate with King David’s (prophet Dawud’s) chamber, for followers of the three Abrahamic faiths: the crusaders named it “King David’s Gate.” It is one of the seven main stone portals of the walled city of Jerusalem.

“Taxi to Bethlehem, taxi to Jericho!” the man at a tourism kiosk is shouting, as I make my way from the tram to Jaffa Gate, known also as Hebron Gate, to Muslims as “Bab al Khalil,” or “door of the friend,” named after Hebron where the prophet Ibrahim/Abraham (Khalil al Allah “God’s Friend”) is laid to rest. Of significance too, is the association of this gate with King David’s (prophet Dawud’s) chamber, for followers of the three Abrahamic faiths: the crusaders named it “King David’s Gate.” It is one of the seven main stone portals of the walled city of Jerusalem.

To reach the street level at the train station in Jerusalem, one must take four escalators up, three of them vertiginously long. I’m reminded that this is the city of ascensions: miracles associated with Abraham, Jesus and Muhammad. The ancient, sacred expanse, rises up as an invisible, vertical cityscape. Jerusalem’s silhouette is cast in the worshippers’ perception of the heavens— avenues in the air— leading to a divine promise. The tragedy of the spirit agonizing to make peace with God as it barters peace with fellow-humans, is more raw here than anywhere else. Read more »

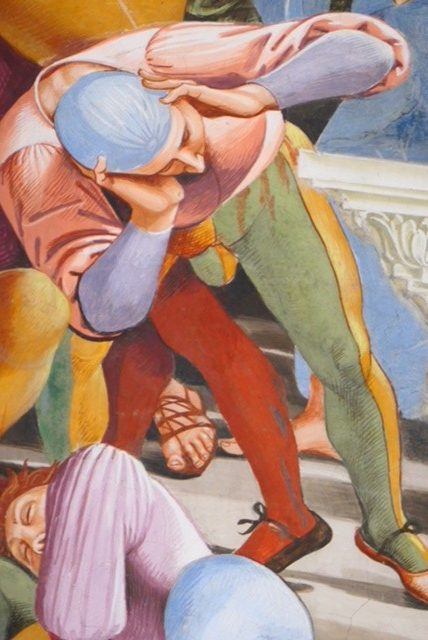

Cropping Vision: The masterpiece inside the masterpiece

by Brooks Riley

It’s not every day that a small, unexpected masterpiece shows up in your mailbox, arriving with the same modest ‘ping’ that announces the other electronic missives. This was no ordinary masterpiece. It was the photograph of a detail from Luca Signorelli’s fresco La Fine del Mondo on the entrance wall of La Cappella di San Brizio in Orvieto, the work itself a masterpiece of painterly skill and imagination, dating from ca.1500. It was taken by a good friend who spent several days with the monumental Signorelli frescoes on the interior walls of the cathedral of Orvieto.

The masterpiece I received, one small element of the arched fresco, achieved its rarified aesthetic status from having been isolated by the photographer for the frame, an act of proto-cropping used by anyone who’s ever put his eye to a viewfinder—or for that matter, anyone who’s ever opened his eyes.

We are all born with a cropping tool: It’s called focus. When we wake up in the morning, the eyes flutter open, we leave our cerebral home with its latent, chimerical images and are confronted by a giant canvas with millions of details, fuzzy around the outer edges, stretching out a full 180 degrees. Without a thought, we begin to cut away the dull bits, homing in on the alarm clock, the window, our phones, a doorknob, maybe even our fingernails. This is how we maneuver our way through the day and through life, cropping the big picture to highlight the parts we actually need to see at any given moment. Most of our time and attention are devoted to the details we’ve cropped from our greater field of vision, whether it’s the utensils we use, or the paths we take, or the signs we read.

In photography, cropping occurs before the picture is taken. Read more »

Burning Down the House

Alan Weisman in the New York Review of Books:

Climate scientists’ worst-case scenarios back in 2007, the first year the Northwest Passage became navigable without an icebreaker (today, you can book a cruise through it), have all been overtaken by the unforeseen acceleration of events. No one imagined that twelve years later the United Nations would report that we have just twelve years left to avert global catastrophe, which would involve cutting fossil-fuel use nearly by half. Since 2007, the UN now says, we’ve done everything wrong. New coal plants built since the 2015 Paris climate agreement have already doubled the equivalent coal-energy output of Russia and Japan, and 260 more are underway.

Climate scientists’ worst-case scenarios back in 2007, the first year the Northwest Passage became navigable without an icebreaker (today, you can book a cruise through it), have all been overtaken by the unforeseen acceleration of events. No one imagined that twelve years later the United Nations would report that we have just twelve years left to avert global catastrophe, which would involve cutting fossil-fuel use nearly by half. Since 2007, the UN now says, we’ve done everything wrong. New coal plants built since the 2015 Paris climate agreement have already doubled the equivalent coal-energy output of Russia and Japan, and 260 more are underway.

Environmental writers today have a twofold problem. First, how to overcome readers’ resistance to ever-worsening truths, especially when climate-change denial has turned into a political credo and a highly profitable industry with its own television network (in this country, at least; state-controlled networks in autocracies elsewhere, such as Cuba, Singapore, Iran, or Russia, amount to the same thing). Second, in view of the breathless pace of new discoveries, publishing can barely keep up. Refined models continually revise earlier predictions of how quickly ice will melt, how fast and high CO2 levels and seas will rise, how much methane will be belched from thawing permafrost, how fiercely storms will blow and fires will burn, how long imperiled species can hang on, and how soon fresh water will run out (even as they try to forecast flooding from excessive rainfall). There’s a real chance that an environmental book will be obsolete by its publication date.

More here.

The Physics of Dissent

Erica Chenoweth in Nature:

The recent revolutions in Algeria and Sudan remind us that bottom-up movements of people power can create sweeping political transformations. They did this in part by mobilizing huge numbers of active protestors—1 million in Algeria, and around 1 million in Sudan—which constituted impressive numbers in absolute terms. Yet due to coordination problems and the possibility of free riding—where those who stay on the side-lines can benefit from the results of mass mobilization without paying the costs or assuming the risk of participation—few mass movements have been able to mobilize significant proportions of their population. Algeria’s peak event during its “Smile Revolution” reportedly mobilized under 2.5% of the country’s population to effectively topple Bouteflika’s government in March 2019. And Sudan’s ongoing revolution, which reportedly mobilized fewer than 2.5% of Sudan’s national population, has already toppled the 30-year role of Omar al-Bashir and forced the transitional military council into a transitional power-sharing agreement with the opposition.

The recent revolutions in Algeria and Sudan remind us that bottom-up movements of people power can create sweeping political transformations. They did this in part by mobilizing huge numbers of active protestors—1 million in Algeria, and around 1 million in Sudan—which constituted impressive numbers in absolute terms. Yet due to coordination problems and the possibility of free riding—where those who stay on the side-lines can benefit from the results of mass mobilization without paying the costs or assuming the risk of participation—few mass movements have been able to mobilize significant proportions of their population. Algeria’s peak event during its “Smile Revolution” reportedly mobilized under 2.5% of the country’s population to effectively topple Bouteflika’s government in March 2019. And Sudan’s ongoing revolution, which reportedly mobilized fewer than 2.5% of Sudan’s national population, has already toppled the 30-year role of Omar al-Bashir and forced the transitional military council into a transitional power-sharing agreement with the opposition.

How do people power movements succeed while mobilizing modest proportions of the population? And how can dissidents successfully assess their power along the way? In our paper, we begin to answer these questions by turning to a simple metaphor: the physical law of momentum.

More here.

Modi’s act of tyranny in Kashmir will soon be the blueprint for all of India

Kavita Krishnan in The Independent:

The Hindu-supremacist government of India, headed by Narendra Modi, has just carried out a coup of India’s constitution and with Kashmir’s autonomy. Jammu and Kashmir has been “put in its place”: stripped not only of its nominal autonomy but even of its status as a state of the Indian union, and summarily demoted to a “union territory” administered by the central government.

The Hindu-supremacist government of India, headed by Narendra Modi, has just carried out a coup of India’s constitution and with Kashmir’s autonomy. Jammu and Kashmir has been “put in its place”: stripped not only of its nominal autonomy but even of its status as a state of the Indian union, and summarily demoted to a “union territory” administered by the central government.

In preparation for this stealthy move, 35,000 troops were flown to Kashmir Valley, which was already one of the most militarised regions of the world. Following the government’s announcement, 8,000 more paramilitary troops have been deployed to the same region.

The people of Jammu and Kashmir have no access to phones or internet. And the leaders of their parliamentary parties, as well as human rights activists and trade unionists are all under arrest. For three days and counting, Kashmir’s newspapers have not been published.

The ruling Bharatiya Janata Party and its parent organisation, Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh, have long maintained that Article 370 is superfluous to the Instrument of Accession binding Kashmir to India, and is a result of a blunder by India’s first prime minister Jawaharlal Nehru. These claims are easily disproved.

‘Semicolon’ Is the Story of a Small Mark That Can Carry Big Ideas

Parul Sehgal in the New York Times:

Writers have their pet themes, favorite words, stubborn obsessions. But their signature, the essence of their style, is felt someplace deeper — at the level of pulse. Style is first felt in rhythm and cadence, from how sentences build and bend, sag or snap. Style, I’d argue, is 90 percent punctuation.

Writers have their pet themes, favorite words, stubborn obsessions. But their signature, the essence of their style, is felt someplace deeper — at the level of pulse. Style is first felt in rhythm and cadence, from how sentences build and bend, sag or snap. Style, I’d argue, is 90 percent punctuation.

“Maman died today. Or yesterday maybe, I don’t know.” “For a man of his age, 52, divorced, he has, to his mind, solved the problem of sex rather well.” “124 was spiteful. Full of a baby’s venom.”

Every sentence is a performance, or should be, and punctuation sets the stage. It signals the rise and fall of the curtain, provides the special effects, etches out the grain in the voices we recognize above as Camus, J.M. Coetzee, Toni Morrison — even inducting us into the themes and tone of the novels. See those ironic commas in Coetzee’s “Disgrace” sequestering “to his mind” or the opening lines of Morrison’s “Beloved,” with one sentence sliced so suddenly, jaggedly into two.

In “Semicolon,” Cecelia Watson reveals punctuation, as we practice it, to be a relatively young and uneasy art. Her lively “biography” tells the story of a mark with an unusual talent for controversy.

More here.

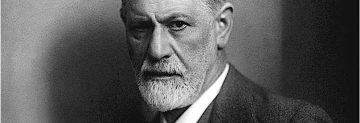

How Would Freud Explain Populism?

Alfred Tauber in iai:

One of the explanations for the rise of populist nationalist myths today goes back to the complicated dynamics between the individual and society, and between reason and fantasy. The thinker who might help us understand our current political storms is no other than Sigmund Freud. Freud is best known for his more controversial theories on sexuality. But we need not buy Freudian mechanics or his clinical theories. Enough of value remains without Oedipus. Freudian theory explores the tension between unconscious desires and the controlling ego, whose rational faculties, while fallible, may be marshalled to scrutinise our emotional drives. On this account, the freedom that humans possess rests solely in recognising and controlling fantasies and the passions that accompany them. With such awareness we are, at least, in a better position to judge and direct our actions – mitigating those that are destructive and strengthening the beneficial. This isn’t a new idea for western philosophy, and it goes at least as far back as Plato and Aristotle.

One of the explanations for the rise of populist nationalist myths today goes back to the complicated dynamics between the individual and society, and between reason and fantasy. The thinker who might help us understand our current political storms is no other than Sigmund Freud. Freud is best known for his more controversial theories on sexuality. But we need not buy Freudian mechanics or his clinical theories. Enough of value remains without Oedipus. Freudian theory explores the tension between unconscious desires and the controlling ego, whose rational faculties, while fallible, may be marshalled to scrutinise our emotional drives. On this account, the freedom that humans possess rests solely in recognising and controlling fantasies and the passions that accompany them. With such awareness we are, at least, in a better position to judge and direct our actions – mitigating those that are destructive and strengthening the beneficial. This isn’t a new idea for western philosophy, and it goes at least as far back as Plato and Aristotle.

Freud, however, remained circumspect about “the arrogance of consciousness.” He recognised the limits of the psychoanalytical method. Consequently, his own guarded view of self-awareness led him to acknowledge our irrationality and to be suspicious of reason as a faculty of self-knowing. Freud thereby undermined confidence in the very Enlightenment ideals he espoused.

More here.

How Wordsworth and Coleridge shaped each other

Frances Wilson in New Statesman:

In Footsteps: Adventures of a Romantic Biographer, Richard Holmes described how, aged 18, he followed the route taken by Robert Louis Stevenson and his donkey almost 100 years earlier as they walked through the Massif Central in France. Sleeping, as Stevenson did, beneath the stars, bathing in rivers, and feeling half mad on the excess of liberty, Holmes learned that his vocation was to live like a ghost crab in another man’s shell. No one has described better the strange and obsessive nature of biographical pursuit, and the business of “footstepping” has since become associated with the Holmesian style of method-biography, in which the biographical subject returns from the dead with a palpable physical presence.

In Footsteps: Adventures of a Romantic Biographer, Richard Holmes described how, aged 18, he followed the route taken by Robert Louis Stevenson and his donkey almost 100 years earlier as they walked through the Massif Central in France. Sleeping, as Stevenson did, beneath the stars, bathing in rivers, and feeling half mad on the excess of liberty, Holmes learned that his vocation was to live like a ghost crab in another man’s shell. No one has described better the strange and obsessive nature of biographical pursuit, and the business of “footstepping” has since become associated with the Holmesian style of method-biography, in which the biographical subject returns from the dead with a palpable physical presence.

Adam Nicolson makes plain his debt to Richard Holmes: “I think of this book as a tributary to the great Holmesian stream,” he says in the introductory chapter to The Making of Poetry. “Its method is his: to follow in the footsteps of the great, looking to gather the fragments they left on the path, much as Dorothy Wordsworth was seen by an old man as she was accompanying her brother on a walk in the Lake District, keeping ‘close behind him, and she picked up the bits as he let ’em fall, and tak ’em down, and put ’em on paper for him’.” The image of Nicolson as Dorothy, picking up the lines dropped on the road by Wordsworth as he went “bumming and booing” about, is wonderfully apt not least because Nicolson’s own sensibility – his ear, his eye, his sense of place and the intensity of his concentration on words, plants, foliage and light – recalls that of Dorothy Wordsworth. The Making of Poetry is indeed a tributary to the great Holmesian stream, and also a tribute to the Romantic art of observational note-taking.

More here.

David Berman (1967 – 2019)

Toni Morrison (1931 – 2019)

Marisa Merz (1926 – 2019)

Sunday Poem

American Cavewall Sonnet

Wolf milk and wilderness America.

Romulus and Remus built a city

but it couldn’t hide the animal in

their hearts: a river-child discovers blood

when he searches for a blessing. Hold your

motherland in your mouth, all marble and

doomed, a single lozenge of loss. Heaven

fell into the pond and killed all the fish.

Even in the shape of a boy I can

wear the morning. Daisies behind my ear.

Minutes thin gold arm hairs. Blackberry vine

tied around my wrist. Under this field is

the only battle my father lost. Place

your ear right here if you want to listen

from the EcoTheo Review

by

The Opioid and Trump Addictions: Symptoms of the Same Malaise

Marshall Sahlins in Counterpunch:

Marshall Sahlins in Counterpunch:

The journalist and author Sam Quinones became aware of it even before the 2016 election, when he saw those Trump/Pence yard signs all over opioid country. Within days of Trump’s electoral victory, he published the disturbing story, as did the historian Kathleen Frydl under the apt title, “The Oxy Electorate.”

Donald Trump did very well, much better than Mitt Romney had in 2012, in the areas hardest hit by a raging drug epidemic. Indeed, one could describe the main opioid victims in exactly the same demographic terms that pundits use to characterize the core of Trump’s electoral support: non-Hispanic, mostly working-class whites without a college education living in rural areas and small cities. The opioid and Trump addictions, the one individual and the other collective, are symptoms of the same malaise.

For one, they are driven by sane powerful economic forces, gainfully employed in afflicting a vulnerable population. The rapacious, unregulated capitalism of the kind that now shapes the Trump agenda prepared the ground of the opioid crisis in Appalachia, the Midwest Rust Belt, and elsewhere by engendering the inequalities and hardships that drive so many to despair.

More here.

Hungary: How Liberty Can Be Lost

The late Anges Heller in Public Seminar:

The late Anges Heller in Public Seminar:

As the Bible (Exodus) teaches and, more recently, Hannah Arendt warns, liberation is not yet liberty. The institutions of liberty must first be constituted, and people need to learn how to make them work while breathing spirit into them.

The years 1989–1991 were a time of liberation for all the people of Eastern Europe who had suffered totalitarian political systems and ideological indoctrination under Soviet domination. The future, the fate, of all liberated nations depended on the success or failure of transforming liberation into liberty. Some of the just-liberated nations did fairly well, others less so. In Hungary in 1989, enthusiasm for system change was great among intellectuals who were spiritually starving for liberty. A considerable part of the population shared this enthusiasm, believing that the establishment of democratic institutions would immediately lead to the Western standard of living. Thus, they expected a far better life.

For a while, all previously Soviet-dominated countries were developing in a similar direction. Later, however, differences became as important as similarities. The Hungarian case proved unique, since only Hungary went through a second system change, not only de facto but also de jure. The prime minister of Hungary, Victor Orbán, described the result of the second system change as “illiberal democracy” and as “the system of national collaboration” (I discuss this more below).

The result proves that, in Hungary, a great opportunity was wasted and aborted: the opportunity to let liberal democracy take root in Hungarian soil. Instead, Hungarians seem to have relied on a longstanding tradition of following a leader, expecting everything from above, believing, or pretending to believe, everything they are told, mixed with a kind of fatalistic cynicism of the impossibility of things being otherwise.

More here.

Toni Morrison, Activist

Joy James in Boston Review:

Joy James in Boston Review:

Released only weeks before the author’s death on August 5, Toni Morrison: The Pieces I Am opens with artist Mickalene Thomas making a collage of an elderly Morrison superimposed upon an image of her as a young woman, embellished with flowers and patterned fabrics. The force of black art dominates the documentary—not only Morrison’s own words, but images from twenty-one prominent black artists including Kara Walker and Faith Ringgold, all shown atop a lush score composed by Kathryn Bostic. The emotional richness of the film skillfully pulls viewers into the unique power of Morrison’s fiction. However, its nearly exclusive focus on her novels—and its progressive liberal depiction of Morrison as a singular genius—sidelines Morrison’s political impact as an editor and essayist, creating a strangely lopsided impression of her life and impact.

In the late sixties and early seventies, before she was known as an author, Morrison was a Random House trade editor who almost singlehandedly introduced black radical activists to mainstream American readers. No single editor or major publishing house has surpassed Morrison’s contribution in the intervening four decades. Cofounder of the Black Panther Party Huey P. Newton (To Die for the People, 1972); prison activist and Black Panther field marshal George Jackson (Blood in My Eye, 1971); and Angela Davis (Angela Davis: An Autobiography, 1974) were all published by Morrison at Random House. Morrison did not necessarily embrace these ideologies, but believed it was invaluable that they circulate in the marketplace of ideas—despite their demonization by the U.S. government.

More here.

Behemoth Rises Again

Andreas Huyssen in n+1:

Andreas Huyssen in n+1:

There is no question that radical right-wing fringe phenomena have been normalized under Donald Trump, most spectacularly when he claimed that there were good people on both sides in the Charlottesville riots. What used to be called the lunatic fringe in American politics is being made respectable by such pronouncements, as well as by the euphemism of “alt-right” itself, a term innocuous enough to disguise its white supremacist ideology. Adorno also warned that the afterlife of fascist tendencies within democracy is more dangerous than the afterlife of fascist tendencies against democracy. Today we face a situation where Adorno’s distinction has been cashed in. Tendencies from within, brilliantly analyzed by Wendy Brown in her 2015 book Undoing the Demos: Neoliberalism’s Stealth Revolution, are merging in the US with outright tendencies against democracy. The Trump regime participates in both. Just think of the Republicans’ systematic attacks on voting rights through gerrymandering, recently legitimized by the Supreme Court. Or compare Mark Zuckerberg’s motto “move fast and break things” with Trump’s daily practice of attacking and dismantling American governmental institutions, a practice that is fully in sync with Steve Bannon’s demand to “deconstruct the administrative state” and with Breitbart’s call to attack the “Democrat media complex” online. Trump uses Twitter and his fake “fake news” mantra to gaslight the electorate, while much of the real deconstruction of governmental institutions regarding the law and the constitution, health care, the environment, housing, foreign policy, and climate change rarely catches the headlines in any sustained fashion. While right-wing parties in the European Union are gaining ground, with few exceptions they are not (yet) the mainstream. In the United States, the Republicans are the mainstream and further to the right than either the AfD in Germany or the latest incarnation of the National Front in France.

More here.

The Utopian Promise of Adorno’s ‘Open Thinking,’ Fifty Years On

Peter E. Gordon in The New York Review of Books:

The German philosopher and social theorist Theodor W. Adorno died fifty years ago this week, in the late summer of 1969. Even at the time of his death, he was entangled in controversy. Student militants, many of them aligned with the so-called “extra-parliamentary opposition,” had once seen him as a political ally. But when they occupied the Institute for Social Research at the Goethe–University Frankfurt, where Adorno kept his office, he called in the police, an act that was seen as unforgivable by the student radicals: How could a theorist of anti-fascism side with the authorities?

Adorno’s decision opened a bitter divide between the so-called Frankfurt School and the more militant members of the student movement that would never truly heal. In late April 1969, when Adorno commenced the first of his lectures on “An Introduction to Dialectical Thinking,” two students rushed the podium, demanding that Adorno engage in a public act of self-criticism. Three female students then showered him with flower petals and bared their breasts. The aging professor fled the hall, and students distributed a leaflet: “Adorno as an Institution is Dead.”

A month later, in an interview for Der Spiegel, Adorno remarked on the irony that in a piece of political theater he had been cast in the unlikely role of a cultural conservative: “To target me, I who have always positioned myself against every kind of erotic repression and sexual taboos!” Adorno tried to resume instruction in June, but further protests prevented him from lecturing.

More here.

On Punctuation’s Occult Power

Ed Simon at The Millions:

However, it was an invention seven years earlier that restructured not just how language appears, but indeed the very rhythm of sentences; for, in 1496, Manutius introduced a novel bit of punctuation, a jaunty little man with leg splayed to the left as if he was pausing to hold open a door for the reader before they entered the next room, the odd mark at the caesura of this byzantine sentence that is known to posterity as the semicolon. Punctuation exists not in the wild; it is not a function of how we hear the word, but rather of how we write the Word. What the theorist Walter Ong described in his classic Orality and Literacy as being marks that are “even farther from the oral world than letters of the alphabet are: though part of a text they are unpronounceable, nonphonemic.” None of our notations are implied by mere speech, they are creatures of the page: comma, and semicolon; (as well as parenthesis and what Ben Jonson appropriately referred to as an “admiration,” but what we call an exclamation mark!)—the pregnant pause of a dash and the grim finality of a period. Has anything been left out? Oh, the ellipses…

However, it was an invention seven years earlier that restructured not just how language appears, but indeed the very rhythm of sentences; for, in 1496, Manutius introduced a novel bit of punctuation, a jaunty little man with leg splayed to the left as if he was pausing to hold open a door for the reader before they entered the next room, the odd mark at the caesura of this byzantine sentence that is known to posterity as the semicolon. Punctuation exists not in the wild; it is not a function of how we hear the word, but rather of how we write the Word. What the theorist Walter Ong described in his classic Orality and Literacy as being marks that are “even farther from the oral world than letters of the alphabet are: though part of a text they are unpronounceable, nonphonemic.” None of our notations are implied by mere speech, they are creatures of the page: comma, and semicolon; (as well as parenthesis and what Ben Jonson appropriately referred to as an “admiration,” but what we call an exclamation mark!)—the pregnant pause of a dash and the grim finality of a period. Has anything been left out? Oh, the ellipses…

more here.