Charlie Wood in Quanta:

Imagine winding the hour hand of a clock back from 3 o’clock to noon. Mathematicians have long known how to describe this rotation as a simple multiplication: A number representing the initial position of the hour hand on the plane is multiplied by another constant number. But is a similar trick possible for describing rotations through space? Common sense says yes, but William Hamilton, one of the most prolific mathematicians of the 19th century, struggled for more than a decade to find the math for describing rotations in three dimensions. The unlikely solution led him to the third of just four number systems that abide by a close analog of standard arithmetic and helped spur the rise of modern algebra.

Imagine winding the hour hand of a clock back from 3 o’clock to noon. Mathematicians have long known how to describe this rotation as a simple multiplication: A number representing the initial position of the hour hand on the plane is multiplied by another constant number. But is a similar trick possible for describing rotations through space? Common sense says yes, but William Hamilton, one of the most prolific mathematicians of the 19th century, struggled for more than a decade to find the math for describing rotations in three dimensions. The unlikely solution led him to the third of just four number systems that abide by a close analog of standard arithmetic and helped spur the rise of modern algebra.

The real numbers form the first such number system. A sequence of numbers that can be ordered from least to greatest, the reals include all the familiar characters we learn in school, like –3.7, 5–√ and 42. Renaissance algebraists stumbled upon the second system of numbers that can be added, subtracted, multiplied and divided when they realized that solving certain equations demanded a new number, i, that didn’t fit anywhere on the real number line. They took the first steps off that line and into the “complex plane,” where misleadingly named “imaginary” numbers couple with real numbers like capital letters pair with numerals in the game of Battleship. In this planar world, “complex numbers” represent arrows that you can slide around with addition and subtraction or turn and stretch with multiplication and division.

More here.

On February 22, 2012, when the British photojournalist Paul Conroy survived the artillery barrage that

On February 22, 2012, when the British photojournalist Paul Conroy survived the artillery barrage that  The human mind wants to worry. This is not necessarily a bad thing — after all, if a bear is stalking you, worrying about it may well save your life. Although most of us don’t need to lose too much sleep over bears these days, modern life does present plenty of other reasons for concern: terrorism, climate change, the rise of A.I., encroachments on our privacy, even the apparent decline of international cooperation.

The human mind wants to worry. This is not necessarily a bad thing — after all, if a bear is stalking you, worrying about it may well save your life. Although most of us don’t need to lose too much sleep over bears these days, modern life does present plenty of other reasons for concern: terrorism, climate change, the rise of A.I., encroachments on our privacy, even the apparent decline of international cooperation. The notion of mattering is intimately linked with the notion of attention. To say that something matters is to assert that attention is due it, the kind of attention that both recognises and reveals its reality. Something that matters has a nature that demands to be known, and the knowledge may yield other attitudes and behaviour due it. If I say that something doesn’t matter, I’m saying that it’s not worth paying attention to.

The notion of mattering is intimately linked with the notion of attention. To say that something matters is to assert that attention is due it, the kind of attention that both recognises and reveals its reality. Something that matters has a nature that demands to be known, and the knowledge may yield other attitudes and behaviour due it. If I say that something doesn’t matter, I’m saying that it’s not worth paying attention to. Can a melody provide us with pleasure? Plato certainly thought so, as do many today. But it’s incredibly difficult to discern just how this comes to pass. Is it something about the flow and shape of a tune that encourages you to predict its direction and follow along? Or is it that the lyrics of a certain song describe a scene that reminds you of a joyful time? Perhaps the melody is so familiar that you’ve simply come to identify with it.

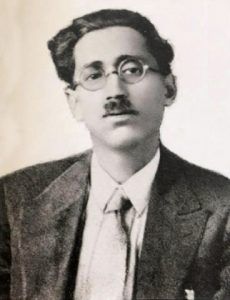

Can a melody provide us with pleasure? Plato certainly thought so, as do many today. But it’s incredibly difficult to discern just how this comes to pass. Is it something about the flow and shape of a tune that encourages you to predict its direction and follow along? Or is it that the lyrics of a certain song describe a scene that reminds you of a joyful time? Perhaps the melody is so familiar that you’ve simply come to identify with it. Mirza Azeem Baig Chughtai has been maligned, misunderstood and pigeonholed as a humourist — which indeed he was; his short stories ‘Yakka’ and ‘Al Shizri’ have been immortalised by the rendition of the legendary Zia Mohyeddin. But other erroneous theories about him have also been made. In ‘Literary Notes: Azeem Baig Chughtai, Sadomasochist or Playful Humourist?’ published in Dawn on Aug 22, 2016, for example, Rauf Parekh considered speculation by literary stalwarts Dr Muhammad Sadiq and Dr Vazeer Agha who believed Chughtai suffered from “depression” and was a “sadomasochist”. Not so. The tantalising title of the piece aside, Parekh rightfully stated that these writers were being “perhaps, all too unsympathetic.”

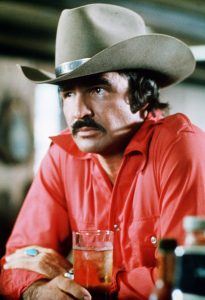

Mirza Azeem Baig Chughtai has been maligned, misunderstood and pigeonholed as a humourist — which indeed he was; his short stories ‘Yakka’ and ‘Al Shizri’ have been immortalised by the rendition of the legendary Zia Mohyeddin. But other erroneous theories about him have also been made. In ‘Literary Notes: Azeem Baig Chughtai, Sadomasochist or Playful Humourist?’ published in Dawn on Aug 22, 2016, for example, Rauf Parekh considered speculation by literary stalwarts Dr Muhammad Sadiq and Dr Vazeer Agha who believed Chughtai suffered from “depression” and was a “sadomasochist”. Not so. The tantalising title of the piece aside, Parekh rightfully stated that these writers were being “perhaps, all too unsympathetic.” For pop-culture enthusiasts of the seventies and eighties, reports of the death of Burt Reynolds, at age eighty-two, of a heart attack, in Jupiter, Florida, may have come as an unexpected shock. Some of us imagined him as eternally youthful, wisecracking, knowingly amused. Reynolds was a genial presence who seemed to have it all—in his heyday, he was the country’s top box-office star for five years; later, he lived in a sprawling estate called Valhalla—and remain a good sport. (His memoir, from 2015, is called “But Enough About Me.”) He was an amiable king of machismo, hairy chests, and highway-focussed buddy comedies, and his friendly sexiness—onscreen and on the covers of tabloids and glossy magazines—was for many years a constant. His groundbreaking

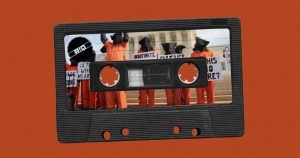

For pop-culture enthusiasts of the seventies and eighties, reports of the death of Burt Reynolds, at age eighty-two, of a heart attack, in Jupiter, Florida, may have come as an unexpected shock. Some of us imagined him as eternally youthful, wisecracking, knowingly amused. Reynolds was a genial presence who seemed to have it all—in his heyday, he was the country’s top box-office star for five years; later, he lived in a sprawling estate called Valhalla—and remain a good sport. (His memoir, from 2015, is called “But Enough About Me.”) He was an amiable king of machismo, hairy chests, and highway-focussed buddy comedies, and his friendly sexiness—onscreen and on the covers of tabloids and glossy magazines—was for many years a constant. His groundbreaking  One of the more unusual methods employed by US interrogators to break the will of detainees during harsh interrogation at Abu Ghraib, Bagram, Mosul, and elsewhere is the use of loud music. The 2006 edition of the US Army’s field manual for interrogation advocated the use of abusive sound as a method of interrogation, a practice corroborated by former detainees who were subject to this abuse. At Guantánamo, inmates reported being held in chains without food or water in total darkness “with loud rap or heavy metal blaring for weeks at a time.” This music played several roles during interrogation. It provoked fear, distress, and disorientation, crowding out the thoughts of the detainee and bending their will to the interrogators’. Even when played at excruciatingly high volume (often as loud as 100 decibels during harsh interrogation, the equivalent of a jackhammer), music leaves no marks on detainees and sheds no blood; it inflicts severe physical and psychological pain without betraying any evidence of its source.

One of the more unusual methods employed by US interrogators to break the will of detainees during harsh interrogation at Abu Ghraib, Bagram, Mosul, and elsewhere is the use of loud music. The 2006 edition of the US Army’s field manual for interrogation advocated the use of abusive sound as a method of interrogation, a practice corroborated by former detainees who were subject to this abuse. At Guantánamo, inmates reported being held in chains without food or water in total darkness “with loud rap or heavy metal blaring for weeks at a time.” This music played several roles during interrogation. It provoked fear, distress, and disorientation, crowding out the thoughts of the detainee and bending their will to the interrogators’. Even when played at excruciatingly high volume (often as loud as 100 decibels during harsh interrogation, the equivalent of a jackhammer), music leaves no marks on detainees and sheds no blood; it inflicts severe physical and psychological pain without betraying any evidence of its source. Austin thought that philosophical perplexities were generated by failing to attend to such distinctions and, in particular, by failing to acknowledge the importance of the illocutionary act. One example arises from attempts to treat stating something as a locutionary rather than an illocutionary act, and so as something that is achieved just by uttering a meaningful sentence. The apparent variety of things we do in speaking would then be treated as mere differences in perlocutionary effects that arise from stating something in different circumstances. Thus, for example, uttering the sentence, “I promise that I’ll be home for dinner”, would be treated as a way of stating something about oneself, rather than as a way of promising. Promising itself would be a perlocutionary effect of making such a statement about oneself. It would consequently be perplexing to try to understand what precisely one was stating about oneself, and how stating it could bring about promising. Furthermore, the locutionary treatment makes it too easy to state something, requiring only that one utter a meaningful sentence; whereas, in fact, stating, like promising, is dependent on propitious circumstances for its successful performance. The treatment leads to puzzlement about what was stated by the utterance of some meaningful sentence in cases in which absence of the required circumstances means that no such stating occurred.

Austin thought that philosophical perplexities were generated by failing to attend to such distinctions and, in particular, by failing to acknowledge the importance of the illocutionary act. One example arises from attempts to treat stating something as a locutionary rather than an illocutionary act, and so as something that is achieved just by uttering a meaningful sentence. The apparent variety of things we do in speaking would then be treated as mere differences in perlocutionary effects that arise from stating something in different circumstances. Thus, for example, uttering the sentence, “I promise that I’ll be home for dinner”, would be treated as a way of stating something about oneself, rather than as a way of promising. Promising itself would be a perlocutionary effect of making such a statement about oneself. It would consequently be perplexing to try to understand what precisely one was stating about oneself, and how stating it could bring about promising. Furthermore, the locutionary treatment makes it too easy to state something, requiring only that one utter a meaningful sentence; whereas, in fact, stating, like promising, is dependent on propitious circumstances for its successful performance. The treatment leads to puzzlement about what was stated by the utterance of some meaningful sentence in cases in which absence of the required circumstances means that no such stating occurred. Throughout his life, the poet Rainer Maria Rilke (1875 -1926) wrote letters to close friends as well as individuals who had read his poetry but did not know him personally. At the time of his death in 1926 at the age of 51, Rilke had written over 14,000 letters which he considered to be as significant and worthy of publication as his poetry and prose. Among this vast correspondence are 23 letters of condolence. For nearly 100 years, most of their sometimes bracing and always powerful insights have been hidden in plain sight, or rather buried in a disorganized and partly irretrievable set of publications and archives on two continents. They have now been gathered for the first time into a short volume that offers Rilke’s highly original and accessible reflections on loss, grief and mortality. Together they tell a story leading from an unflinching and honest acknowledgment of death to transformation, just as Rilke’s well-known Letters to a Young Poet recounts the story from unflinching self-reckoning and the acceptance of solitude to serious self-transformation. Taken individually, each of the letters on loss, which Rilke wrote to different recipients but with the same single-minded intent to assist someone in mourning, may offer solace for anyone dealing with a personal loss. What can we say in the face of loss, when words seem too frail and ordinary to convey grief and soothe the pain? How can we provide solace for the bereaved, when even time, as Rilke stresses over and over, cannot properly console but only “put things in order”? These letters offer guidance in the effort to recover our voice during periods of loss and grief, and not to let even the most devastating experiences overwhelm, numb and silence us. —Ulrich Baer

Throughout his life, the poet Rainer Maria Rilke (1875 -1926) wrote letters to close friends as well as individuals who had read his poetry but did not know him personally. At the time of his death in 1926 at the age of 51, Rilke had written over 14,000 letters which he considered to be as significant and worthy of publication as his poetry and prose. Among this vast correspondence are 23 letters of condolence. For nearly 100 years, most of their sometimes bracing and always powerful insights have been hidden in plain sight, or rather buried in a disorganized and partly irretrievable set of publications and archives on two continents. They have now been gathered for the first time into a short volume that offers Rilke’s highly original and accessible reflections on loss, grief and mortality. Together they tell a story leading from an unflinching and honest acknowledgment of death to transformation, just as Rilke’s well-known Letters to a Young Poet recounts the story from unflinching self-reckoning and the acceptance of solitude to serious self-transformation. Taken individually, each of the letters on loss, which Rilke wrote to different recipients but with the same single-minded intent to assist someone in mourning, may offer solace for anyone dealing with a personal loss. What can we say in the face of loss, when words seem too frail and ordinary to convey grief and soothe the pain? How can we provide solace for the bereaved, when even time, as Rilke stresses over and over, cannot properly console but only “put things in order”? These letters offer guidance in the effort to recover our voice during periods of loss and grief, and not to let even the most devastating experiences overwhelm, numb and silence us. —Ulrich Baer Two Harvard scholars

Two Harvard scholars

I sometimes play a game with my cat, Cleo. I stand around the corner from her, just out of sight. She starts to sneak towards me. When I poke my head around the corner to look at her, she freezes. When I pull back, she carries on sneaking. Eventually, she pounces on my ankles.

I sometimes play a game with my cat, Cleo. I stand around the corner from her, just out of sight. She starts to sneak towards me. When I poke my head around the corner to look at her, she freezes. When I pull back, she carries on sneaking. Eventually, she pounces on my ankles. Slate today is taking the rare step of publishing a letter someone sent us from inside an ongoing bank robbery. We have done so at the request of the author, who is currently robbing a bank, but would like to minimize his exposure to criminal charges from this whole bank robbery thing now that it seems to be going south. We invite you to submit a question about this essay or our vetting process

Slate today is taking the rare step of publishing a letter someone sent us from inside an ongoing bank robbery. We have done so at the request of the author, who is currently robbing a bank, but would like to minimize his exposure to criminal charges from this whole bank robbery thing now that it seems to be going south. We invite you to submit a question about this essay or our vetting process  It’s a rare children’s book, Heneghan notes, that doesn’t have a wilderness interlude; but then he has to consider exactly what is meant by “wilderness”. It is doubtful if nature at its most extreme and untrammelled can exist in the world today, since even the wildest of wild places are shaped by the activities of people as well as natural forces. He cites as an example the Burren in Co Clare, along with the bogs and mountainy country of the west of Ireland ‑ all territories that have evolved over millennia as a consequence of human intervention in the landscape. However, if wilderness, or quasi-wilderness, occurs at one end of the environmental spectrum and the densely populated city at the other end, what occupies the space between them is denoted by the word “pastoral”, and this makes a highly fruitful ground for children’s stories. Section Two of Beasts at Bedtime considers the pastoral impulse in writing for children, with due attention paid to Pooh, Peter Rabbit, Rat and Mole, Bilbo Baggins, the Ugly Duckling and others. (But we miss Rupert, whose picture-strip adventures encompass many aspects of pastoral: woodland, meadowland, fields, hills, seaside, streams, lily ponds, cottage gardens … all the way to underground caverns and cannibal islands. And you’d have to say that Rupert, in one sense, goes one better than Winnie-the-Pooh. In AA Milne’s stories a little boy plays with his bear; with Rupert, the little boy is the bear.)

It’s a rare children’s book, Heneghan notes, that doesn’t have a wilderness interlude; but then he has to consider exactly what is meant by “wilderness”. It is doubtful if nature at its most extreme and untrammelled can exist in the world today, since even the wildest of wild places are shaped by the activities of people as well as natural forces. He cites as an example the Burren in Co Clare, along with the bogs and mountainy country of the west of Ireland ‑ all territories that have evolved over millennia as a consequence of human intervention in the landscape. However, if wilderness, or quasi-wilderness, occurs at one end of the environmental spectrum and the densely populated city at the other end, what occupies the space between them is denoted by the word “pastoral”, and this makes a highly fruitful ground for children’s stories. Section Two of Beasts at Bedtime considers the pastoral impulse in writing for children, with due attention paid to Pooh, Peter Rabbit, Rat and Mole, Bilbo Baggins, the Ugly Duckling and others. (But we miss Rupert, whose picture-strip adventures encompass many aspects of pastoral: woodland, meadowland, fields, hills, seaside, streams, lily ponds, cottage gardens … all the way to underground caverns and cannibal islands. And you’d have to say that Rupert, in one sense, goes one better than Winnie-the-Pooh. In AA Milne’s stories a little boy plays with his bear; with Rupert, the little boy is the bear.) From March through July, some lucky thousands in New York could experience the perihelion of one of our most noble projects. “A Synthesis of Intuitions,” Piper’s retrospective at the Museum of Modern Art in New York, the largest the museum has ever devoted to a living artist, brought together work from 1965 to 2016, the latter date representing the cusp of the latest national crisis. Organized by Christophe Cherix and David Platzker at MoMA, along with Connie Butler at the Hammer Museum in Los Angeles, where a version of the show opens on October 7,1 the exhibition collected the works of a genius who has given herself to a relentless, life-affirming engagement—in philosophy, in art—with the fundamental operations of xenophobia. It contained records of the investigation of certain tools (dance, reason, confrontation, aggressive politesse, dance) to understand and target and then transform the mechanisms that divide people into groups and distribute resources according to unjust criteria.

From March through July, some lucky thousands in New York could experience the perihelion of one of our most noble projects. “A Synthesis of Intuitions,” Piper’s retrospective at the Museum of Modern Art in New York, the largest the museum has ever devoted to a living artist, brought together work from 1965 to 2016, the latter date representing the cusp of the latest national crisis. Organized by Christophe Cherix and David Platzker at MoMA, along with Connie Butler at the Hammer Museum in Los Angeles, where a version of the show opens on October 7,1 the exhibition collected the works of a genius who has given herself to a relentless, life-affirming engagement—in philosophy, in art—with the fundamental operations of xenophobia. It contained records of the investigation of certain tools (dance, reason, confrontation, aggressive politesse, dance) to understand and target and then transform the mechanisms that divide people into groups and distribute resources according to unjust criteria.