by Dave Maier

So Sam Harris, Jordan Peterson, and a number of other brash rebels daring to challenge the stifling intellectual status quo, in which one is not allowed to criticize anyone from other cultures, because multiculturalism or Marxism or something, are part of, I am not making this up, the Intellectual Dark Web. Fine, whatever. It’s not that there’s no such thing as lefty orthodoxy, obviously, especially on campus, but these best-selling authors look pretty petty presenting themselves as somehow being silenced.

Anyway, that’s not what I want to talk about. In the New York Times piece telling us about all this, I ran across the following exchange:

After [Harris’s] talk, in which he disparaged the Taliban, a biologist who would go on to serve on President Barack Obama’s Commission for the Study of Bioethical Issues approached him. “I remember she said: ‘That’s just your opinion. How can you say that forcing women to wear burqas is wrong?’ But to me it’s just obvious that forcing women to live their lives inside bags is wrong. I gave her another example: What if we found a culture that was ritually blinding every third child? And she actually said, ‘It would depend on why they were doing it.’” His jaw, he said, “actually fell open.”

It’s not unprecedented, or even unusual, that Harris should commit a philosophy fail. But in detaching ourselves from error, we have to be careful about where we end up. It’s not even clear, for example, that his point in the context is threatened by his futile sally. So I’ll be defending him as much as diagnosing his (all too common) error. Maybe I should be on the IDW too. Help, I’m being silenced!

Okay, enough japery for now. What did Harris do wrong here, and why may his main point survive the stumble? Read more »

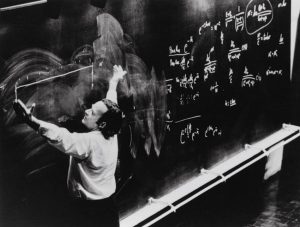

On May 11th, to mark the 100th anniversary of Richard Feynman’s birth, Caltech put on a truly dazzling evening of public talks. I heard that tickets sold-out online in four minutes; and this event was so popular that attendees started queueing up to enter the auditorium an hour before the program began. Held in Caltech’s

On May 11th, to mark the 100th anniversary of Richard Feynman’s birth, Caltech put on a truly dazzling evening of public talks. I heard that tickets sold-out online in four minutes; and this event was so popular that attendees started queueing up to enter the auditorium an hour before the program began. Held in Caltech’s

30 years ago I moved from the UK to New York City and I gave up my car. I had mixed feelings about doing so at the time – I was only 21 and driving was still a novelty and an expression of independence. When I moved out of New York City to upstate 13 years later, I again became a car owner and regular driver. After my divorce, when I moved back to New York City, I once again gave up my car, this time happily. I would honestly be thrilled if I never had to get behind the wheel of a car again. I don’t enjoy driving, I’m not the most confident driver (I cannot reverse to save my life even after over 30 years of driving) and I generally would prefer to be driven. My transportation needs are now taken care of by a combination of public transport, ride sharing services and a boyfriend with a car who is very good about driving me around. And thanks to online shopping, the retail convenience of a car ownership has almost totally disappeared. As far as I’m concerned, this is a perfect state of affairs.

30 years ago I moved from the UK to New York City and I gave up my car. I had mixed feelings about doing so at the time – I was only 21 and driving was still a novelty and an expression of independence. When I moved out of New York City to upstate 13 years later, I again became a car owner and regular driver. After my divorce, when I moved back to New York City, I once again gave up my car, this time happily. I would honestly be thrilled if I never had to get behind the wheel of a car again. I don’t enjoy driving, I’m not the most confident driver (I cannot reverse to save my life even after over 30 years of driving) and I generally would prefer to be driven. My transportation needs are now taken care of by a combination of public transport, ride sharing services and a boyfriend with a car who is very good about driving me around. And thanks to online shopping, the retail convenience of a car ownership has almost totally disappeared. As far as I’m concerned, this is a perfect state of affairs.  The freer the market, the more people suffer.

The freer the market, the more people suffer.

It’s with a certain pleasure that I can recall the exact moment I was seduced by the musical avant-garde. It was in the fourth grade, in a public elementary school somewhere in New Jersey. Our music teacher, Mrs. Jones, would visit the classroom several times a week, accompanied by an ancient record player and a stack of LPs. You could always tell when she was coming down the hall because the wheels of the cart had a particularly squeak-squeak-wheeze pattern. However, such a Cageian sensibility was not the occasion of my epiphany. I’m also not sure if fourth-graders are allowed to have epiphanies, or, which is likelier, if they are not having them on a daily basis.

It’s with a certain pleasure that I can recall the exact moment I was seduced by the musical avant-garde. It was in the fourth grade, in a public elementary school somewhere in New Jersey. Our music teacher, Mrs. Jones, would visit the classroom several times a week, accompanied by an ancient record player and a stack of LPs. You could always tell when she was coming down the hall because the wheels of the cart had a particularly squeak-squeak-wheeze pattern. However, such a Cageian sensibility was not the occasion of my epiphany. I’m also not sure if fourth-graders are allowed to have epiphanies, or, which is likelier, if they are not having them on a daily basis.

If by “objectivity” we mean “wholly lacking personal biases”, in wine tasting, this idea can be ruled out. There are too many individual differences among wine tasters, regardless of how much expertise they have acquired, to aspire to this kind of objectivity. But traditional aesthetics has employed a related concept which does seem attainable—an attitude of disinterestedness, which provides much of what we want from objectivity. We can’t eliminate differences among tasters that arise from biology or life history, but we can minimize the influence of personal motives and desires that might distort the tasting experience.

If by “objectivity” we mean “wholly lacking personal biases”, in wine tasting, this idea can be ruled out. There are too many individual differences among wine tasters, regardless of how much expertise they have acquired, to aspire to this kind of objectivity. But traditional aesthetics has employed a related concept which does seem attainable—an attitude of disinterestedness, which provides much of what we want from objectivity. We can’t eliminate differences among tasters that arise from biology or life history, but we can minimize the influence of personal motives and desires that might distort the tasting experience.

Dr Abdus Salam had once said, “It became quite clear to me that either I must leave my country or leave physics. And with great anguish, I chose to leave my country.”

Dr Abdus Salam had once said, “It became quite clear to me that either I must leave my country or leave physics. And with great anguish, I chose to leave my country.” A new theory seldom comes into the world like a fully formed, beautiful infant, ready to be coddled and embraced by its parents, grandparents and relatives. Rather, most new theories make their mark kicking and screaming while their fathers and grandfathers try to disown, ignore or sometimes even hurt them before accepting them as equivalent to their own creations. Ranging from Darwin’s theory of evolution by natural selection to Wegener’s theory of continental drift, new ideas in science have faced scientific, political and religious resistance. There are few better examples of this jagged, haphazard, bruised birth of a new theory as the scientific renaissance that burst forth in a mountain resort during the spring of 1948.

A new theory seldom comes into the world like a fully formed, beautiful infant, ready to be coddled and embraced by its parents, grandparents and relatives. Rather, most new theories make their mark kicking and screaming while their fathers and grandfathers try to disown, ignore or sometimes even hurt them before accepting them as equivalent to their own creations. Ranging from Darwin’s theory of evolution by natural selection to Wegener’s theory of continental drift, new ideas in science have faced scientific, political and religious resistance. There are few better examples of this jagged, haphazard, bruised birth of a new theory as the scientific renaissance that burst forth in a mountain resort during the spring of 1948.