by Richard Passov

Robert Gordon is the Stanley G. Harris Professor of Social Sciences at Northwestern University. In a well-received book, The Rise and Fall of American Growth, Gordon ‘…contributes to resolving one of the most fundamental questions about American economic history’ by providing ‘… a comprehensive and unified explanation of why productivity growth was so fast between 1920 and 1970 and so slow thereafter.’

The ability to control electricity so that it arrives in measured doses where and when needed combined with simple steps to improve public sanitation, such as running water, indoor toilets and the removal of the uncountable tons of horse manure that marked major cities before the advent of the internal combustion engine that spurred roads and transportation networks that enabled frozen food to be enjoyed from coast to coast, wrought a step change in living standards unlikely to be repeated.

The ability to control electricity so that it arrives in measured doses where and when needed combined with simple steps to improve public sanitation, such as running water, indoor toilets and the removal of the uncountable tons of horse manure that marked major cities before the advent of the internal combustion engine that spurred roads and transportation networks that enabled frozen food to be enjoyed from coast to coast, wrought a step change in living standards unlikely to be repeated.

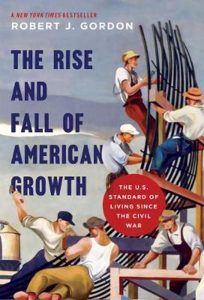

Economists know the growth in Gross Domestic Product (GDP) in any period. And total hours worked and the change in capital. They apportion contributions from labor and capital to GDP based on the amounts of income they ascribe to labor and capital. What remains – the residual that’s necessary to arrive at the total growth in GDP – is Total Factor Productivity (TFP). You can think of this as conflating, in the measured period, smarter workers working harder with more and better capital. Or as one equation with three unknowns.

Going into WWII, TFP was elevated: jobs were scarce and to remain in business, an enterprise had to be extremely productive. During WWII, as Gordon points out, Government built an enormous amount of plant and equipment that was retooled to meet the pent-up demands of a population starved for consumer goods. So no great surprise that the US continued to benefit from surging TFP post WWII.

Since 1970, according to Gordon, TFP has been missing. I know where some of it can be found.

* * *

Recently, I spent a few hot days in Phoenix Arizona at the Bondurant School of driving.

On our first morning, three instructors perched on a table at the front of the class. Will was the lead. For the next few days I’d hear his flat delivery coordinating track time over the radio. Tyler, boyish and rail-thin, was assigned to Camaro drivers. The third instructor approached my group. “Well,” he said, “you guys must be here for the Corvette class. I’ll be working with you. ” Read more »

The ability to control electricity so that it arrives in measured doses where and when needed combined with simple steps to improve public sanitation, such as running water, indoor toilets and the removal of the uncountable tons of horse manure that marked major cities before the advent of the internal combustion engine that spurred roads and transportation networks that enabled frozen food to be enjoyed from coast to coast, wrought a step change in living standards unlikely to be repeated.

The ability to control electricity so that it arrives in measured doses where and when needed combined with simple steps to improve public sanitation, such as running water, indoor toilets and the removal of the uncountable tons of horse manure that marked major cities before the advent of the internal combustion engine that spurred roads and transportation networks that enabled frozen food to be enjoyed from coast to coast, wrought a step change in living standards unlikely to be repeated.

“It’s a long, long way from the Trump administration to an actual fascist dictatorship,” I said, “but it’s a straight line.”

“It’s a long, long way from the Trump administration to an actual fascist dictatorship,” I said, “but it’s a straight line.” It was all another day of Trump TV. Another day when all eyes were on Trump. Another day when headlines ran with his name splashed across the front page all over the world. Another day when memes were shared on Facebook and twitter. And another day people expressed feeling incredibly offended over and over again.

It was all another day of Trump TV. Another day when all eyes were on Trump. Another day when headlines ran with his name splashed across the front page all over the world. Another day when memes were shared on Facebook and twitter. And another day people expressed feeling incredibly offended over and over again.

Give me a break I mutter. I text—and I text. Incessantly I text. Send money. Now. Send money. More money. You don’t reply. You will. It is Spring and I am young. Everyone around me on the beach is around my age or younger. We are young.

Give me a break I mutter. I text—and I text. Incessantly I text. Send money. Now. Send money. More money. You don’t reply. You will. It is Spring and I am young. Everyone around me on the beach is around my age or younger. We are young.

Political debates in Europe these days seem to have only one subject. At one point or another they all turn to the issue of migration, Islam, and a danger to “the West”, which are presented as essentially synonymous. Germany’s political future seems currently to

Political debates in Europe these days seem to have only one subject. At one point or another they all turn to the issue of migration, Islam, and a danger to “the West”, which are presented as essentially synonymous. Germany’s political future seems currently to

“In receiving this award, I thank my parents, Zsa Zsa Gabor and Mr. T.”

“In receiving this award, I thank my parents, Zsa Zsa Gabor and Mr. T.”