by Scott F. Aikin and Robert B. Talisse

Democracy is many things: a form of constitutional republic, a system of government, a procedure for collective decision, a method for electing public officials, a collection of processes by which conflicts among competing preferences are domesticated, a means for creating social stability, and so on. But underneath all of these common ways of understanding democracy lies a commitment to the distinctively moral ideal of collective self-government among political equals. And this commitment to the political equality of citizens is what explains the familiar mechanisms of democratic government. Our elections, representative bodies, constitution, and system of law and rights of redress are intended to preserve individual political equality in the midst of large-scale government. Absent the presumption of political equality, much of what goes on in a democracy would be difficult to explain. Why else would we bother with the institutional inefficiency, the collective irrationality, and the noise of democracy, but for the commitment to the idea that government must be of, for, and by the People, understood as political equals?

To be clear, the democrat’s commitment to the political equality of the citizens does not amount to the idea that all citizens are the same, or equally good and admirable, or equal in every respect. Political equality is the commitment to the idea that in politics, no one is another’s subordinate. Put differently, among political equals, all political power is accountable to those over whom it is exercised. Accordingly, although in a democracy there are laws and rules of other kinds that all citizens are obligated to obey, no one is ever reduced to being a mere subject of legislation. In a democracy, even when a law has been produced by impeccably democratic processes, citizens who nonetheless oppose it may still enact various forms of protest, critique, and resistance. Under certain conditions, citizens may also be permitted to engage in civil disobedience. Once again, the democratic thought is that where citizens have rights to object, oppose, and criticize exercises of political power under conditions where government is accountable to its citizens, they retain their status as political equals even while being subject to the law. In this way, democracy is commonly thought to be the only viable response to the moral problem of reconciling the political power with the fundamental equality of those over whom power is exercised. Read more »

I write this as Saturday begins to wane on the long Columbus Day weekend while I listen on the radio to the speeches given by senator after senator prior to the final confirmation vote for Bret Kavanaugh as Associate Justice on the Supreme Court of the United States of America. The vote is scheduled for 3.30 p.m. October 6, 2016. I listen to their conflicted words in the Senate of the United States pleading yes or no, or yes and no. Conjuring images, I am reminded of that Roman mythology and the artists’ rendition of it, of the Rape of the Sabine Women.

I write this as Saturday begins to wane on the long Columbus Day weekend while I listen on the radio to the speeches given by senator after senator prior to the final confirmation vote for Bret Kavanaugh as Associate Justice on the Supreme Court of the United States of America. The vote is scheduled for 3.30 p.m. October 6, 2016. I listen to their conflicted words in the Senate of the United States pleading yes or no, or yes and no. Conjuring images, I am reminded of that Roman mythology and the artists’ rendition of it, of the Rape of the Sabine Women.

My

My

Every October there’s a huge book fair in my town, where used books donated by the community are put up for sale in a large hall at the fairgrounds. It’s no exaggeration to say that it’s a high point of my year.

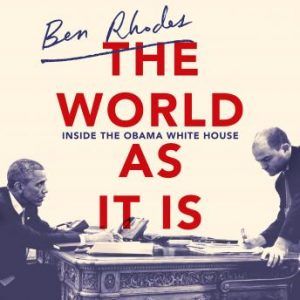

Every October there’s a huge book fair in my town, where used books donated by the community are put up for sale in a large hall at the fairgrounds. It’s no exaggeration to say that it’s a high point of my year. As the first African American president of the United States (US), Barack Obama is a uniquely historical personality. Each of us has our opinions, or will formulate opinions, as to the success or limitations of his eight years in office as a Democratic president from 2009-2017, and as to the person who is Obama. Helping us in the formulation of our views on Obama and his presidency, is Ben Rhodes book, The World As It Is: Inside the Obama White House.

As the first African American president of the United States (US), Barack Obama is a uniquely historical personality. Each of us has our opinions, or will formulate opinions, as to the success or limitations of his eight years in office as a Democratic president from 2009-2017, and as to the person who is Obama. Helping us in the formulation of our views on Obama and his presidency, is Ben Rhodes book, The World As It Is: Inside the Obama White House.  One of the most simple, elegant and powerful formulations of the conflict between science and religion is the following bit of reasoning. ‘Faith’ is belief in the absence of evidence; science demands that beliefs are always grounded in evidence. Therefore, the two are mutually exclusive. This is an oft-repeated argument by modern atheists, and it connects different aspects of what is usually called the ‘Conflict Thesis’: the idea that science and religion are opposed to each other not just now, but always and necessarily.

One of the most simple, elegant and powerful formulations of the conflict between science and religion is the following bit of reasoning. ‘Faith’ is belief in the absence of evidence; science demands that beliefs are always grounded in evidence. Therefore, the two are mutually exclusive. This is an oft-repeated argument by modern atheists, and it connects different aspects of what is usually called the ‘Conflict Thesis’: the idea that science and religion are opposed to each other not just now, but always and necessarily.