by Andrea Scrima

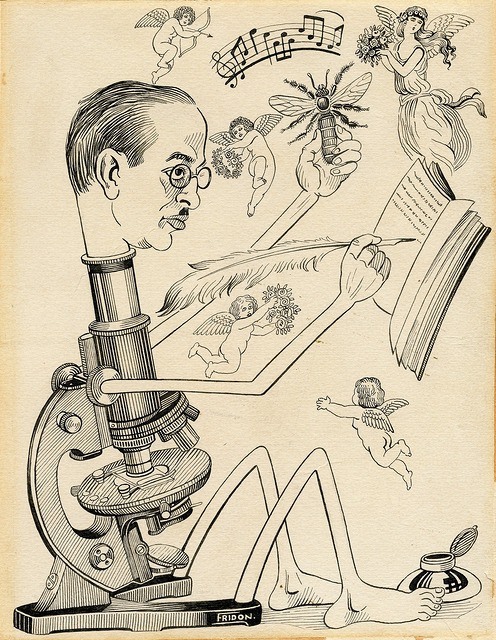

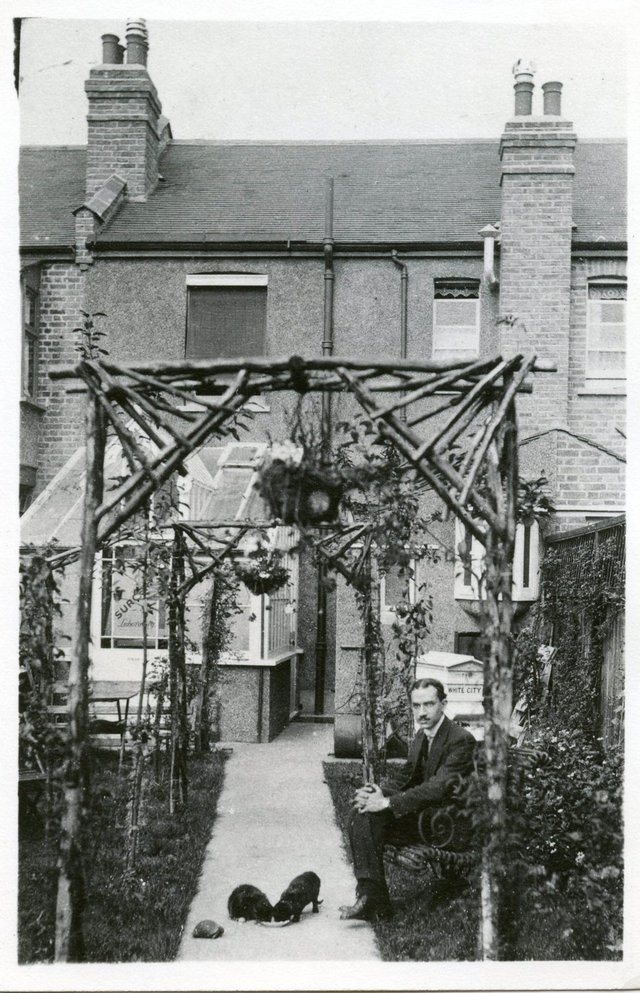

Joy Amina Garnett is an Egyptian American artist and writer living in New York. Her work, which spans creative writing, painting, installation art, and social media-based projects, reflects how past, present, and future narratives can co-exist through ‘the archive’ in its various forms. Her work has been included in exhibitions at New York’s FLAG Art Foundation, MoMA–PS1, the James Gallery, the Milwaukee Art Museum, Museum of Contemporary Craft Portland, Boston University Art Gallery, and the Witte Zaal in Ghent, Belgium, and she has been awarded grants from Anonymous Was a Woman, the Lower Manhattan Cultural Council, Wellcome Trust, and the Chipstone Foundation. Joy’s paintings and writings have appeared, sometimes side-by-side, in an eclectic array of publications, including the Evergreen Review, Ibraaz, edible Brooklyn, C Magazine, Ping Pong, and The Artists’ and Writers’ Cookbook. She has been working on a memoir and several other projects around the life and work of her late grandfather, the Egyptian Romantic poet and bee scientist A.Z. Abushady (1892–1955). Her chapter on Abushady will appear in Cultural Entanglement in the Pre-Independence Arab World: Arts, Thought, and Literature, edited by Anthony Gorman and Sarah Irving, forthcoming from I.B. Tauris. An excerpt from her memoir-in-progress appears in the January 2019 issue of FULL BLEDE, edited by Sacha Baumann.

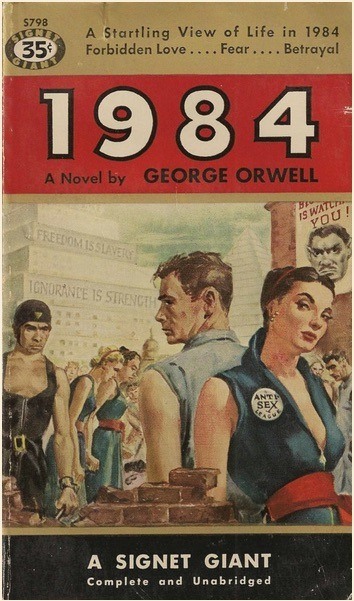

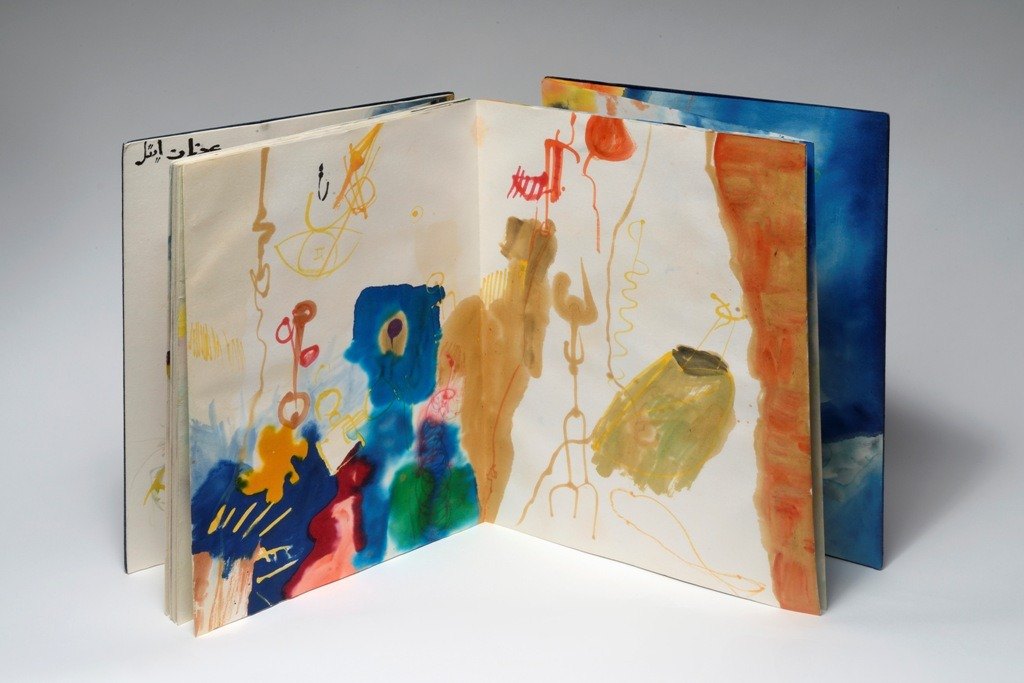

Andrea Scrima: Joy, you’re the sole steward of the effects of your famous grandfather—the Egyptian Romantic poet and bee scientist Ahmed Zaki Abushady [Abu Shadi]—and have been compiling an archive for several years. First of all, however, I’d like to ask you about your artistic approach to the material and the ways in which history and storytelling interweave in the work. You showed an earlier version of this work-in-progress at Smack Mellon around four years ago, and now, recently, I’ve seen a number of new installments of The Bee Kingdom on Facebook. It makes me think of a kind of novel of layered fragments.

Joy Garnett: I like that description, The Bee Kingdom as a novel of layered fragments, though sometimes it feels like I’m chasing a moving target. It’s been challenging to parlay so many fragments into an artwork or a sustained piece of creative writing, but that is what I’m doing. The source material is not only historically relevant, it’s close and personal, and this affects how I work. And while I want to know the history of what actually happened to my grandfather and my family, and so on, I’m aware of many co-existing unofficial and even secret histories that appear and disappear as I try to make sense of things.

There are other questions, such as what types of media I want to work with. I’ve been a painter all my life, but painting isn’t right for this project. Is The Bee Kingdom mostly writing? Yes and no. I’ve subordinated the visual to writing, but the writing depends heavily on images. Read more »

Okay. I’m done. I’m through. I’m hanging up my ruby red slippers, my fuck-me shoes. I’m not going down that yellow brick road no more, no more. I’m giving up internet dating. I may have run a successful antique business in Portobello Road for many years which kept my three children in fish fingers, the three little children I was left with in the middle of Somerset – where I kept chickens, made bread and grew my own veg – when I was 31 and they were all under 6. I may have dragged myself off as a mature student up to the University of East Anglia, after I’d moved us like Ms Whittington to London, to do an MA in Creative Writing with the crème de la crème, whilst juggling child care as the other students hung out talking postmodernism in the bar. I may have written for Time Out, The Independent and The New Statesman as an art critic, published three collections of poetry, one of short stories and three novels but none of this is as anything compared to my failure with internet dating.

Okay. I’m done. I’m through. I’m hanging up my ruby red slippers, my fuck-me shoes. I’m not going down that yellow brick road no more, no more. I’m giving up internet dating. I may have run a successful antique business in Portobello Road for many years which kept my three children in fish fingers, the three little children I was left with in the middle of Somerset – where I kept chickens, made bread and grew my own veg – when I was 31 and they were all under 6. I may have dragged myself off as a mature student up to the University of East Anglia, after I’d moved us like Ms Whittington to London, to do an MA in Creative Writing with the crème de la crème, whilst juggling child care as the other students hung out talking postmodernism in the bar. I may have written for Time Out, The Independent and The New Statesman as an art critic, published three collections of poetry, one of short stories and three novels but none of this is as anything compared to my failure with internet dating.

I know you’ve heard this before. But it’s just too relevant to avoid, so, please, bear with me. It may, or may not, be a garbled version of something Bertrand Russell wrote in Why I am not a Christian, but it has become the equivalent of an urban legend in philosophy. It goes like this. Some famous philosopher or another, maybe Russell, maybe William James, is traveling in some non-Western country, probably India, because of the elephants, and they ask a local informant about their cosmology. The local says, “We believe that the world is a vast sphere resting on the back of four great elephants.”

I know you’ve heard this before. But it’s just too relevant to avoid, so, please, bear with me. It may, or may not, be a garbled version of something Bertrand Russell wrote in Why I am not a Christian, but it has become the equivalent of an urban legend in philosophy. It goes like this. Some famous philosopher or another, maybe Russell, maybe William James, is traveling in some non-Western country, probably India, because of the elephants, and they ask a local informant about their cosmology. The local says, “We believe that the world is a vast sphere resting on the back of four great elephants.”

No one knows if it was really in the state prison, the ruins of which are visible today outside the ancient Agora of Athens, that Socrates was kept during the final days before his execution, so many times has the area been destroyed and reconstructed— walking past it sends a chill down my spine. Ancient Greece is visceral and vivid because it entered my imagination early in life; some of the most cherished tales of my childhood came from the crossovers of Hellenistic history and legend, such as the one in which Sikander (Alexander the Great) is accompanied by the Quranic Saint Khizr, in pursuit of “aab e hayat,” the elixir of immortality, or the one about the elephantry in the battle between Sikander and the Indian king Porus, or of the loss of Sikander’s beloved horse Bucephalus on a riverbank not far from Lahore, the city where I was born. I became familiar with ancient Greece through classical Urdu poetry and lore as well as through my study of English literature in Pakistan, but I would read Greek philosophers in depth many years later, as a student at Reed college; I would subsequently discover Greek influence on scholars in the golden age of Muslim civilization while working on a book on al-Andalus— the overlooked, key contribution of Arabic which served as a link between Greek and Latin, and its later offshoots that came to define the cultural and intellectual history of Europe.

No one knows if it was really in the state prison, the ruins of which are visible today outside the ancient Agora of Athens, that Socrates was kept during the final days before his execution, so many times has the area been destroyed and reconstructed— walking past it sends a chill down my spine. Ancient Greece is visceral and vivid because it entered my imagination early in life; some of the most cherished tales of my childhood came from the crossovers of Hellenistic history and legend, such as the one in which Sikander (Alexander the Great) is accompanied by the Quranic Saint Khizr, in pursuit of “aab e hayat,” the elixir of immortality, or the one about the elephantry in the battle between Sikander and the Indian king Porus, or of the loss of Sikander’s beloved horse Bucephalus on a riverbank not far from Lahore, the city where I was born. I became familiar with ancient Greece through classical Urdu poetry and lore as well as through my study of English literature in Pakistan, but I would read Greek philosophers in depth many years later, as a student at Reed college; I would subsequently discover Greek influence on scholars in the golden age of Muslim civilization while working on a book on al-Andalus— the overlooked, key contribution of Arabic which served as a link between Greek and Latin, and its later offshoots that came to define the cultural and intellectual history of Europe.

1. “…And I, who timidly hate life, fascinatedly fear death.” Fernando Pessoa, The Book of Disquiet.

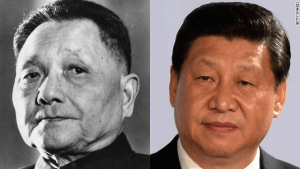

1. “…And I, who timidly hate life, fascinatedly fear death.” Fernando Pessoa, The Book of Disquiet. This is the 40th anniversary of the onset of economic ‘reform and opening-up’ (gaige kaifang) in China under the leadership of Deng Xiaoping, which eventually led to a dramatic transformation of its economy and global status. It is, however, remarkable that China’s current supreme leader, Xi Jinping, marked the anniversary in a speech in the Great Hall of People in Beijing mainly emphasizing the Party’s pervasive control. It is also remarkable that in recent years this leadership seems to have forsaken Deng’s earlier advice of tao guang yang hui (“keep a low profile”). In the flush of Chinese nationalist glory, Xi explicitly stated in the 19th Party Congress that China has now entered a “new era”, when its model “offers a new option for other countries and nations who want to speed up their development while preserving their independence”. Many people both in rich and poor countries seem to be already awe-struck by this model.

This is the 40th anniversary of the onset of economic ‘reform and opening-up’ (gaige kaifang) in China under the leadership of Deng Xiaoping, which eventually led to a dramatic transformation of its economy and global status. It is, however, remarkable that China’s current supreme leader, Xi Jinping, marked the anniversary in a speech in the Great Hall of People in Beijing mainly emphasizing the Party’s pervasive control. It is also remarkable that in recent years this leadership seems to have forsaken Deng’s earlier advice of tao guang yang hui (“keep a low profile”). In the flush of Chinese nationalist glory, Xi explicitly stated in the 19th Party Congress that China has now entered a “new era”, when its model “offers a new option for other countries and nations who want to speed up their development while preserving their independence”. Many people both in rich and poor countries seem to be already awe-struck by this model.

I wrote the first draft of this post on my typewriter. Like much of my other writing, this piece began as handwritten notes and drafts typed on a nice little portable typewriter, which is a little younger than I am and which I expect to use for the rest of my life.

I wrote the first draft of this post on my typewriter. Like much of my other writing, this piece began as handwritten notes and drafts typed on a nice little portable typewriter, which is a little younger than I am and which I expect to use for the rest of my life.