by Michael Klenk

I live and work in two different cities; on the commute, I continuously ask my phone for advice: When’s the next train? Must I take the bus, or can I afford to walk and still make the day’s first meeting? I let my phone direct me to places to eat and things to see, and I’ll admit that for almost any question, my first impulse is to ask the internet for advice.

I live and work in two different cities; on the commute, I continuously ask my phone for advice: When’s the next train? Must I take the bus, or can I afford to walk and still make the day’s first meeting? I let my phone direct me to places to eat and things to see, and I’ll admit that for almost any question, my first impulse is to ask the internet for advice.

My deference to machines puts me in good company. Professionals concerned with mightily important questions are doing it, too, when they listen to machines to determine who is likely to have cancer, pay back their loan, or return to prison. That’s all good insofar as we need to settle clearly defined, factual questions that have computable answers.

Imagine now a wondrous new app. One that tells you whether it is permissible to lie to a friend about their looks, to take the plane in times of global warming, or whether you ought to donate to humanitarian causes and be a vegetarian. An artificial moral advisor to guide you through the moral maze of daily life. With the push of a button, you will competently settle your ethical questions; if many listen to the app, we might well be on our way to a better society.

Concrete efforts to create such artificial moral advisors are already underway. Some scholars herald artificial moral advisors as vast improvements over morally frail humans, as presenting the best opportunity for avoiding the extinction of human life from our own hands. They demand that we should take listen to machines for ethical advice. But should we? Read more »

To follow the popular discourse about the gender wage gap in the United States is to confront perpetual confusion. It is a confusion created at least in part by pronouncements of the type many of us have heard: “Women are paid only 82 cents for every dollar men earn! It is high time for women to earn equal pay for equal work!” Two sentences, each true standing alone, but in juxtaposition creating the impression that the

To follow the popular discourse about the gender wage gap in the United States is to confront perpetual confusion. It is a confusion created at least in part by pronouncements of the type many of us have heard: “Women are paid only 82 cents for every dollar men earn! It is high time for women to earn equal pay for equal work!” Two sentences, each true standing alone, but in juxtaposition creating the impression that the  On occasions, while meandering the various English countryside and woodland paths, I have been pleasantly surprised to come across anglers. I have met fishermen dangling their lines in either a pond in some remote corner of the low-lying areas, or wading in water and casting a line down through the waters of a gently flowing river.

On occasions, while meandering the various English countryside and woodland paths, I have been pleasantly surprised to come across anglers. I have met fishermen dangling their lines in either a pond in some remote corner of the low-lying areas, or wading in water and casting a line down through the waters of a gently flowing river.

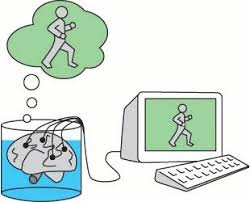

Unfortunately, you have a brain tumor. You don’t know it yet. Your doctor doesn’t know it yet. But you are beginning to have symptoms. The tumor is pressing on surrounding brain tissue and causing you develop a number of delusional beliefs. You believe you are the best swimmer in the world. You believe that dogs and cats are aliens. You believe that you invented the apostrophe. You also, as it happens, believe that you have a brain tumor.

Unfortunately, you have a brain tumor. You don’t know it yet. Your doctor doesn’t know it yet. But you are beginning to have symptoms. The tumor is pressing on surrounding brain tissue and causing you develop a number of delusional beliefs. You believe you are the best swimmer in the world. You believe that dogs and cats are aliens. You believe that you invented the apostrophe. You also, as it happens, believe that you have a brain tumor. “Taxi to Bethlehem, taxi to Jericho!” the man at a tourism kiosk is shouting, as I make my way from the tram to Jaffa Gate, known also as Hebron Gate, to Muslims as “Bab al Khalil,” or “door of the friend,” named after Hebron where the prophet Ibrahim/Abraham (Khalil al Allah “God’s Friend”) is laid to rest. Of significance too, is the association of this gate with King David’s (prophet Dawud’s) chamber, for followers of the three Abrahamic faiths: the crusaders named it “King David’s Gate.” It is one of the seven main stone portals of the walled city of Jerusalem.

“Taxi to Bethlehem, taxi to Jericho!” the man at a tourism kiosk is shouting, as I make my way from the tram to Jaffa Gate, known also as Hebron Gate, to Muslims as “Bab al Khalil,” or “door of the friend,” named after Hebron where the prophet Ibrahim/Abraham (Khalil al Allah “God’s Friend”) is laid to rest. Of significance too, is the association of this gate with King David’s (prophet Dawud’s) chamber, for followers of the three Abrahamic faiths: the crusaders named it “King David’s Gate.” It is one of the seven main stone portals of the walled city of Jerusalem.

Calls for a Manhattan Project–style crash effort to develop artificial intelligence (AI) technology are thick on the ground these days. Oren Etzioni, the CEO of the Allen Institute for Artificial Intelligence, recently issued such a call on

Calls for a Manhattan Project–style crash effort to develop artificial intelligence (AI) technology are thick on the ground these days. Oren Etzioni, the CEO of the Allen Institute for Artificial Intelligence, recently issued such a call on

Fans are the people who know the quotes, the dates of publication, the batting averages, the bassist on this album, the team that general manager coached before. I am not a fan. Don’t get me wrong. I’m full of enthusiasms. But I can’t match you statistic for statistic. I haven’t read the major author’s minor novel. I don’t care who the bassist was. You win. I’m an amateur.

Fans are the people who know the quotes, the dates of publication, the batting averages, the bassist on this album, the team that general manager coached before. I am not a fan. Don’t get me wrong. I’m full of enthusiasms. But I can’t match you statistic for statistic. I haven’t read the major author’s minor novel. I don’t care who the bassist was. You win. I’m an amateur. When I watched the 2019 documentary on Apollo 11, it carried me back not to the summer of 1969, when it happened, but to the mid-1980s, when I was an undergrad. I was eight when Apollo 11 launched; of course I was aware of the space program and the moon landings, but I don’t have any memories of everyone gathering around to watch those first steps on another world. My parents weren’t particularly interested, and I don’t remember being caught by the spirit of the times myself.

When I watched the 2019 documentary on Apollo 11, it carried me back not to the summer of 1969, when it happened, but to the mid-1980s, when I was an undergrad. I was eight when Apollo 11 launched; of course I was aware of the space program and the moon landings, but I don’t have any memories of everyone gathering around to watch those first steps on another world. My parents weren’t particularly interested, and I don’t remember being caught by the spirit of the times myself. cinematic representations of Muslims. Stage One features stereotyped figures (the taxi driver, terrorist, cornershop owner, or oppressed woman). Stage Two involves a portrayal that subverts and challenges those stereotypes. Finally, Stage Three is ‘the Promised Land, where you play a character whose story is not intrinsically linked to his race’. Does

cinematic representations of Muslims. Stage One features stereotyped figures (the taxi driver, terrorist, cornershop owner, or oppressed woman). Stage Two involves a portrayal that subverts and challenges those stereotypes. Finally, Stage Three is ‘the Promised Land, where you play a character whose story is not intrinsically linked to his race’. Does