by John Schwenkler

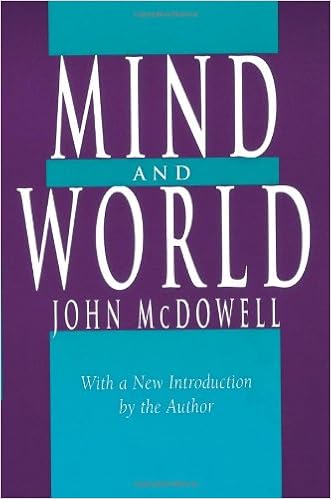

This year marks the 25th anniversary of the publication of Mind and World, a groundbreaking book by the South African-born philosopher John McDowell, who has taught since 1986 at the University of Pittsburgh. The book is based on a series of lectures that McDowell had delivered at the University of Oxford in 1991. The importance of McDowell’s arguments was recognized immediately when the lectures appeared in print, and for many philosophers of my generation an encounter with Mind and World—in my case, within the context of a decade of philosophical work responding to those arguments—was a defining moment in our intellectual development.

This year marks the 25th anniversary of the publication of Mind and World, a groundbreaking book by the South African-born philosopher John McDowell, who has taught since 1986 at the University of Pittsburgh. The book is based on a series of lectures that McDowell had delivered at the University of Oxford in 1991. The importance of McDowell’s arguments was recognized immediately when the lectures appeared in print, and for many philosophers of my generation an encounter with Mind and World—in my case, within the context of a decade of philosophical work responding to those arguments—was a defining moment in our intellectual development.

There is no easy way in to a book that treats fundamental philosophical questions in the manner of Mind and World, but a reasonable place to start is with a passage from Immanuel Kant’s Critique of Pure Reason that frames its overall dialectic. I have set in boldface a crucial sentence that I’ll focus on below:

Our nature is so constituted that our intuition can never be other than sensible; that is, it contains only the mode in which we are affected by objects. The faculty, on the other hand, which enables us to think the object of sensible intuition is the understanding.

To neither of these powers may a preference be given over the other. Without sensibility no object would be given to us, without understanding no object would be thought. Thoughts without content are empty, intuitions without concepts are blind.

It is, therefore, just as necessary to make our concepts sensible, that is, to add the object to them in intuition, as to make our intuitions intelligible, that is, to bring them under concepts.

What Kant calls ‘intuition’ can fairly be glossed as ‘perception’ or ‘sensory experience’: he means that by which our minds are related to particular objects in the world thanks to the way they affect our sensory organs. This contrasts with what he calls the ‘understanding’, through which we think about things using general concepts. The concept horse, for example, is not a concept of any horse in particular. According to Kant, we can apply this concept to a particular horse, say the famed Secretariat, only because we stand in a sensory relation to that horse, or have heard of Secretariat from someone who (has heard of him from someone who has …) encountered Secretariat directly. And this direct encounter is what Kant calls intuition: it’s a way for this particular animal, Secretariat, to become present to our minds, i.e. be ‘given to us’, so that our thinking can be about him in particular. Read more »

An intransigent form of identity politics in combination with neoliberal ideology has left the modern university, if not in ruins, then lacking imagination and cultural capital. It has become a place of sequestered spaces—symbolic and real—where too many students and faculty fear discussing issues deemed to be controversial, inappropriate, or “political.” Across the social sciences/humanities, politics, religion, sex, sexual orientation, climate change, science, gender, economic inequality, poverty, reproductive rights/regulations, homelessness, race, Trump, democracy, capitalism, patriarchy, anti-Semitism, Israel, terrorism, gun violence, sexual violence, and white supremacy are just some of the topics that today make students and even some teachers uncomfortable. At best maybe these topics are addressed by creating some kind of false equivalent in an effort to feign neutrality and keep people comfortable. Discomfort in the classroom from ignorance, tension, power imbalances, conflict, disagreement, or any degree of affective and cognitive dissonance is no longer tolerated. While it used to be considered a fundamental part of the critical learning experience, discomfort of this sort now signals a flaw in pedagogy and/or the curriculum and a betrayal of trust. Learning should always feel good, be nurturing (maternalistic), and, above all, fun. If it’s not then there is hell to pay.

An intransigent form of identity politics in combination with neoliberal ideology has left the modern university, if not in ruins, then lacking imagination and cultural capital. It has become a place of sequestered spaces—symbolic and real—where too many students and faculty fear discussing issues deemed to be controversial, inappropriate, or “political.” Across the social sciences/humanities, politics, religion, sex, sexual orientation, climate change, science, gender, economic inequality, poverty, reproductive rights/regulations, homelessness, race, Trump, democracy, capitalism, patriarchy, anti-Semitism, Israel, terrorism, gun violence, sexual violence, and white supremacy are just some of the topics that today make students and even some teachers uncomfortable. At best maybe these topics are addressed by creating some kind of false equivalent in an effort to feign neutrality and keep people comfortable. Discomfort in the classroom from ignorance, tension, power imbalances, conflict, disagreement, or any degree of affective and cognitive dissonance is no longer tolerated. While it used to be considered a fundamental part of the critical learning experience, discomfort of this sort now signals a flaw in pedagogy and/or the curriculum and a betrayal of trust. Learning should always feel good, be nurturing (maternalistic), and, above all, fun. If it’s not then there is hell to pay.

It doesn’t take much. A small piece of gravel, spit out by a truck’s wheel, ricochets off the windshield, taking a tiny chip of glass with it. A microscopic divot and discreet little lines, like crow’s feet at the corner of an eye. Barely noticed for months, the accordion of heat and cold compress and expand, adding and relieving pressure. Then finally, the scratches spread out across the glass like an avant garde spider web.

It doesn’t take much. A small piece of gravel, spit out by a truck’s wheel, ricochets off the windshield, taking a tiny chip of glass with it. A microscopic divot and discreet little lines, like crow’s feet at the corner of an eye. Barely noticed for months, the accordion of heat and cold compress and expand, adding and relieving pressure. Then finally, the scratches spread out across the glass like an avant garde spider web.

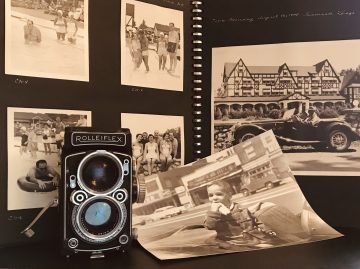

by Leanne Ogasawara

by Leanne Ogasawara

employees, a move that could increase wages and benefits for hundreds of thousands of struggling workers. […]

employees, a move that could increase wages and benefits for hundreds of thousands of struggling workers. […] We’ve seen a couple of these artists before. FernLodge is this guy Joe from Canada, whose music is (as is all of this music actually; follow the links) available on Bandcamp. However, while most artists, even when giving their music away for free, allow you to “name your price” (which in turn allows you, if your price isn’t zero, to put that music into your Bandcamp “collection,” available to download whenever you want), Joe simply sets the price at “free” (which means you can’t put it into your online collection even if you want to). As you can tell by listening, Joe is being way too modest, as

We’ve seen a couple of these artists before. FernLodge is this guy Joe from Canada, whose music is (as is all of this music actually; follow the links) available on Bandcamp. However, while most artists, even when giving their music away for free, allow you to “name your price” (which in turn allows you, if your price isn’t zero, to put that music into your Bandcamp “collection,” available to download whenever you want), Joe simply sets the price at “free” (which means you can’t put it into your online collection even if you want to). As you can tell by listening, Joe is being way too modest, as  Someone else gets more quality time with your spouse, your kids, and your friends than you do. Like most people, you probably enjoy just about an hour, while your new rivals are taking a whopping 2 hours and 15 minutes each day. But save your jealousy. Your rivals are tremendously charming, and you have probably fallen for them as well.

Someone else gets more quality time with your spouse, your kids, and your friends than you do. Like most people, you probably enjoy just about an hour, while your new rivals are taking a whopping 2 hours and 15 minutes each day. But save your jealousy. Your rivals are tremendously charming, and you have probably fallen for them as well.