by Bill Benzon

AI – artificial intelligence – is all the rage these days. Most of the raging, I suspect, is a branding strategy. It is hype. Some of it isn’t, and that’s important. Alas, distinguishing between the hype and the true goods is not easy, even for experts – some of whom have their own dreams, aspirations, and illusions. Here’s my 2 cents on what we do and do not know.

And it’s only that: 2¢. Not a nickel or a dime more, much less a 50 cent piece.

What are computers, animal, vegetable, or mineral?

One of the problems we have in understanding the computer in its various forms is deciding what kind of thing it is, and therefore what sorts of tasks are suitable to it. The computer is ontologically ambiguous. Can it think, or only calculate? Is it a brain or only a machine?

are suitable to it. The computer is ontologically ambiguous. Can it think, or only calculate? Is it a brain or only a machine?

The steam locomotive, the so-called iron horse, posed a similar problem in the nineteenth century. It is obviously a mechanism and it is inherently inanimate. Yet it is capable of autonomous motion, something heretofore only within the capacity of animals and humans. So, is it animate or not? Consider this passage from Henry David Thoreau’s “Sound” chapter in Walden (1854):

When I meet the engine with its train of cars moving off with planetary motion … with its steam cloud like a banner streaming behind in gold and silver wreaths … as if this traveling demigod, this cloud-compeller, would ere long take the sunset sky for the livery of his train; when I hear the iron horse make the hills echo with his snort like thunder, shaking the earth with his feet, and breathing fire and smoke from his nostrils, (what kind of winged horse or fiery dragon they will put into the new Mythology I don’t know), it seems as if the earth had got a race now worthy to inhabit it.

What was Thoreau doing when he wrote of an “iron horse” and a “fiery dragon”? He certainly recognized them as figures. He knew that the thing about which he was talking was some glorified mechanical contraption. He knew it was neither horse nor dragon, nor was it living. Read more »

Last year we drove across the country. We had one cassette tape to listen to on the entire trip. I don’t remember what it was. —Steven Wright

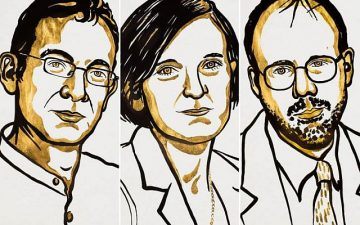

Last year we drove across the country. We had one cassette tape to listen to on the entire trip. I don’t remember what it was. —Steven Wright As a development economist I am celebrating, along with my co-professionals, the award of the Nobel Prize this year to three of our best development economists, Abhijit Banerjee, Esther Duflo and Michael Kremer. Even though the brilliance of these three economists has illuminated a whole range of subjects in our discipline, invariably, the write-ups in the media have referred to their great service to the cause of tackling global poverty, with their experimental approach, particularly the use of Randomized Control Trial (RCT).

As a development economist I am celebrating, along with my co-professionals, the award of the Nobel Prize this year to three of our best development economists, Abhijit Banerjee, Esther Duflo and Michael Kremer. Even though the brilliance of these three economists has illuminated a whole range of subjects in our discipline, invariably, the write-ups in the media have referred to their great service to the cause of tackling global poverty, with their experimental approach, particularly the use of Randomized Control Trial (RCT).

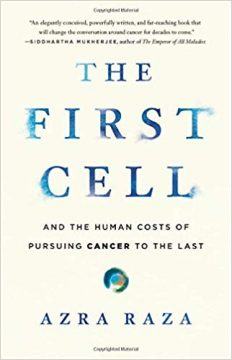

When I was a young attending surgeon on the faculty in the Division of Cardiothoracic Surgery, one of the things I got frequently called for was management of malignant pleural or pericardial effusions. Once a patient develops malignant pleural or pericardial effusion the median survival is only two months, so I would do things that would relieve the acute symptoms and perhaps try to prevent fluid from reaccumulating, but nothing drastic or major. One evening in late October, one of the nurses who had known me called to say that her father was being treated for lung cancer but had to be admitted with a large pleural effusion and that she and her father’s Oncologist would like me to manage it. I met the fine 72-year old retired banker, and while he was short of breath even as he talked, he was in a very upbeat mood. I decided to insert a chest tube to drain the pleural fluid and relieve his symptoms. As I was doing the procedure at the bedside the patient mentioned to me that his oncologist has assured him that once his fluid is out he will start him on a new regimen of chemotherapy and he should expect to live for a few more years. I was disturbed to hear the false hope he was being given.

When I was a young attending surgeon on the faculty in the Division of Cardiothoracic Surgery, one of the things I got frequently called for was management of malignant pleural or pericardial effusions. Once a patient develops malignant pleural or pericardial effusion the median survival is only two months, so I would do things that would relieve the acute symptoms and perhaps try to prevent fluid from reaccumulating, but nothing drastic or major. One evening in late October, one of the nurses who had known me called to say that her father was being treated for lung cancer but had to be admitted with a large pleural effusion and that she and her father’s Oncologist would like me to manage it. I met the fine 72-year old retired banker, and while he was short of breath even as he talked, he was in a very upbeat mood. I decided to insert a chest tube to drain the pleural fluid and relieve his symptoms. As I was doing the procedure at the bedside the patient mentioned to me that his oncologist has assured him that once his fluid is out he will start him on a new regimen of chemotherapy and he should expect to live for a few more years. I was disturbed to hear the false hope he was being given. These energetic lines open Moon and Sun: Rumi’s Rubaiyat, Zara Houshmand’s brilliant translation of selected ruba’iyat – quatrains – by Molana Jalaluddin Rumi, and set the tone for an inspiring and exhilarating sojourn through the passions of the peerless Sage of Konya.

These energetic lines open Moon and Sun: Rumi’s Rubaiyat, Zara Houshmand’s brilliant translation of selected ruba’iyat – quatrains – by Molana Jalaluddin Rumi, and set the tone for an inspiring and exhilarating sojourn through the passions of the peerless Sage of Konya. Sutcliffe views the concept of “disdain” as central to Scarlatti’s approach: the term, first applied to the composer by Italian musicologist Giorgio Pestelli, connotes a deliberate rejection of convention. Scarlatti is well-versed in, but does not fully adopt, the conventions of the

Sutcliffe views the concept of “disdain” as central to Scarlatti’s approach: the term, first applied to the composer by Italian musicologist Giorgio Pestelli, connotes a deliberate rejection of convention. Scarlatti is well-versed in, but does not fully adopt, the conventions of the

One autumn I’m suddenly taller than my mother. The euphoria of wearing her heels and blouses will, for an instant, distract me from the loss of inhabiting the innocence of a child’s body—the hundred scents and stains of tumbling on grass, the anthills and hot powdery breath of brick-walls climbed, the textures of twigs and nodes of branches and wet doll hair and rubber bands, kite paper and tamarind-candy wrappers, the cicada-like sound of pencil sharpeners, the popping of coca cola bottle caps, of cracking pine nuts in the long winter evenings— will blunt and vanish, one by one.

One autumn I’m suddenly taller than my mother. The euphoria of wearing her heels and blouses will, for an instant, distract me from the loss of inhabiting the innocence of a child’s body—the hundred scents and stains of tumbling on grass, the anthills and hot powdery breath of brick-walls climbed, the textures of twigs and nodes of branches and wet doll hair and rubber bands, kite paper and tamarind-candy wrappers, the cicada-like sound of pencil sharpeners, the popping of coca cola bottle caps, of cracking pine nuts in the long winter evenings— will blunt and vanish, one by one.

We are all in some sense equal. Aren’t we? The Declaration of American Independence says that, “We hold these Truths [with a capital ‘T’!] to be self-evident” – number one being “that all Men are created equal.” Immediately, you probably want to amend that. Maybe, not “created”, and surely not only “Men” – and, of course, there’s the painful irony of a group of landed-gentry proclaiming the equality of all men, while also holding (at that point) over 300,000 slaves. But don’t we still believe, all that aside, that all people are, in some sense, equal? Isn’t this a central and orienting principle of our social and political world? What should we say, then, about what equality is for us now?

We are all in some sense equal. Aren’t we? The Declaration of American Independence says that, “We hold these Truths [with a capital ‘T’!] to be self-evident” – number one being “that all Men are created equal.” Immediately, you probably want to amend that. Maybe, not “created”, and surely not only “Men” – and, of course, there’s the painful irony of a group of landed-gentry proclaiming the equality of all men, while also holding (at that point) over 300,000 slaves. But don’t we still believe, all that aside, that all people are, in some sense, equal? Isn’t this a central and orienting principle of our social and political world? What should we say, then, about what equality is for us now? Einstein had called nationalism ‘an infantile disease, the measles of mankind’. Many contemporary cosmopolitan liberals are similarly skeptical, contemptuous or dismissive, as its current epidemic rages all around the world particularly in the form of right-wing extremist or populist movements. While I understand the liberal attitude, I think it’ll be irresponsible of us to let the illiberals meanwhile hijack the idea of nationalism for their nefarious purpose. Nationalism is too passionate and historically explosive an issue to be left to their tender mercies. It is important to fight the virulent forms of the disease with an appropriate antidote and try to vaccinate as many as possible particularly in the younger generations.

Einstein had called nationalism ‘an infantile disease, the measles of mankind’. Many contemporary cosmopolitan liberals are similarly skeptical, contemptuous or dismissive, as its current epidemic rages all around the world particularly in the form of right-wing extremist or populist movements. While I understand the liberal attitude, I think it’ll be irresponsible of us to let the illiberals meanwhile hijack the idea of nationalism for their nefarious purpose. Nationalism is too passionate and historically explosive an issue to be left to their tender mercies. It is important to fight the virulent forms of the disease with an appropriate antidote and try to vaccinate as many as possible particularly in the younger generations.