by Mindy Clegg

In 1994, Miramax Pictures released a small, independently made film by an unknown director from New Jersey named Kevin Smith. Made for a mere $27,000 (maxing out credit cards and the proceeds from selling his comic collection), the black and white film—replete with deeply offensive language, references to drug dealing and usage, and philosophical debates on Star Wars—grossed over $3 million and netted the young director not only a career, but accolades from the Cannes and Sundance film Festivals and nominations in three categories at the Independent Spirit Awards that year.1 It’s since been acknowledged as one of the best indie films of the 1990s.

Clerks, it can be argued, functions as a brilliant example of Gen X slacker culture that prized authenticity over slick production techniques and funny but insightful discourse over spectacle. Smith’s career has been built on that authenticity in community and self-expression, even in films that fall outside of his “View Askewniverse.” Generally speaking, Smith makes films that he wishes to see, not what he thinks will sell, and that was very generationally grounded. He infused his love of endlessly examining comic books and sci-fi/fantasy films/shows with the structure of the rom-com and buddy film genres to carve out a career catering not to all mainstream audiences, but to a like-minded audience of fans who love seeing themselves reflected on the screen.

Part of the enduring popularity of Smith’s work represents various shifts within film and TV making that centers on at least some Gen X sensibilities. His work also signaled a shift in Hollywood finally beginning to take speculative fiction seriously, in part to cater to Gen X (and later millennial and Gen Z tastes). The goal was never superstar status as a filmmaker, but a career that allowed Smith to make the kind of work he himself sought out and enjoyed, which mirrors the Gen X relationship to other cultural forms, too—the rise of the current subcultural society that we live in now. Read more »

American writer Rebecca Solnit laments that few writers have had quite as much scrutiny directed toward their laundry habits as Transcendentalist writer Henry David Thoreau, best known for his 1854 memoir Walden. “Only Henry David Thoreau,” she claims in Orion Magazine’s article “Mysteries of Thoreau, Unsolved,” “has been tried in the popular imagination and found wanting for his cleaning arrangements.”

American writer Rebecca Solnit laments that few writers have had quite as much scrutiny directed toward their laundry habits as Transcendentalist writer Henry David Thoreau, best known for his 1854 memoir Walden. “Only Henry David Thoreau,” she claims in Orion Magazine’s article “Mysteries of Thoreau, Unsolved,” “has been tried in the popular imagination and found wanting for his cleaning arrangements.” Among the best books I’ve read about wine are the two by wine importer Terry Theise.

Among the best books I’ve read about wine are the two by wine importer Terry Theise.

I saw Joker last week. I think it’s an excellent film. But the two friends I was with, whose tastes often overlap with my own, really hated it, and we spent the ensuing 90 minutes examining and debating the film. Critics are likewise fiercely divided. Towards the end of our conversation, one friend admitted that, love it or hate it, the film evokes strong reactions; it’s difficult to ignore.

I saw Joker last week. I think it’s an excellent film. But the two friends I was with, whose tastes often overlap with my own, really hated it, and we spent the ensuing 90 minutes examining and debating the film. Critics are likewise fiercely divided. Towards the end of our conversation, one friend admitted that, love it or hate it, the film evokes strong reactions; it’s difficult to ignore.

The terror of the unforeseen is what the science of history hides, turning a disaster into an epic. —Philip Roth, The Plot Against America

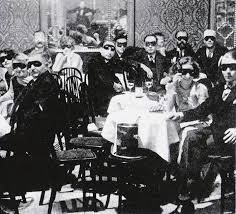

The terror of the unforeseen is what the science of history hides, turning a disaster into an epic. —Philip Roth, The Plot Against America “What is hidden is for us Westerners more ‘true’ than what is visible,” Roland Barthes proposed, in Camera Lucida, his phenomenology of the photograph, almost forty years ago. In the decades since, the internet, nanotechnology, and viral marketing have challenged his privileging of the unseen over the seen by developing a culture of total exposure, heralding the death of interiority and celebrating the cult of instant celebrity. The icon of this movement, the selfie, is now produced and displayed, in endless daily iterations, in a ritual staging of eyewitness testimony to the festival of self-fashioning.

“What is hidden is for us Westerners more ‘true’ than what is visible,” Roland Barthes proposed, in Camera Lucida, his phenomenology of the photograph, almost forty years ago. In the decades since, the internet, nanotechnology, and viral marketing have challenged his privileging of the unseen over the seen by developing a culture of total exposure, heralding the death of interiority and celebrating the cult of instant celebrity. The icon of this movement, the selfie, is now produced and displayed, in endless daily iterations, in a ritual staging of eyewitness testimony to the festival of self-fashioning. Late morning heat rises in waves over tall grass. It’s an hour and a half drive, sand flies buzzing, to Luwi bush camp, a seasonal camp with just four huts of thatch and grass on a still lagoon, far out into Zambia’s South Luangwa National Park, about 300 miles north of Lusaka.

Late morning heat rises in waves over tall grass. It’s an hour and a half drive, sand flies buzzing, to Luwi bush camp, a seasonal camp with just four huts of thatch and grass on a still lagoon, far out into Zambia’s South Luangwa National Park, about 300 miles north of Lusaka.