by Fabio Tollon

We produce data all the time. This is a not something new. Whenever a human being performs an action in the presence of another, there is a sense in which some new data is created. We learn more about people as we spend more time with them. We can observe them, and form models in our minds about why they do what they do, and the possible reasons they might have for doing so. With this data we might even gather new information about that person. Information, simply, is processed data, fit for use. With this information we might even start to predict their behaviour. On an inter-personal level this is hardly problematic. I might learn over time that my roommate really enjoys tea in the afternoon. Based on this data, I can predict that at three o’clock he will want tea, and I can make it for him. This satisfies his preferences and lets me off the hook for not doing the dishes.

The fact that we produce data, and can use it for our own purposes, is therefore not a novel or necessarily controversial claim. Digital technologies (such as Facebook, Google, etc.), however, complicate the simplistic model outlined above. These technologies are capable of tracking and storing our behaviour (to varying degrees of precision, but they are getting much better) and using this data to influence our decisions. “Big Data” refers to this constellation of properties: it is the process of taking massive amounts of data and using computational power to extract meaningful patterns. Significantly, what differentiates Big Data from traditional data analysis is that the patterns extracted would have remained opaque without the resources provided by electronically powered systems. Big Data could therefore present a serious challenge to human decision-making. If the patterns extracted from the data we are producing is used in malicious ways, this could result in a decreased capacity for us to exercise our individual autonomy. But how might such data be used to influence our behaviour at all? To get a handle on this, we first need to understand the common cognitive biases and heuristics that we as humans display in a variety of informational contexts. Read more »

The stories in Seiobo There Below, if they can be called stories, begin with a bird, a snow-white heron that stands motionless in the shallow waters of the Kamo River in Kyoto with the world whirling noisily around it. Like the center of a vortex, the eye in a storm of unceasing, clamorous activity, it holds its curved neck still, impervious to the cars and buses and bicycles rushing past on the surrounding banks, an embodiment of grace and fortitude of concentration as it spies the water below and waits for its prey. We’ve only just begun reading this collection, and already László Krasznahorkai’s haunting prose has submerged us in the great panta rhei of life—Heraclitus’s aphorism that everything flows in a state of continuous change.

The stories in Seiobo There Below, if they can be called stories, begin with a bird, a snow-white heron that stands motionless in the shallow waters of the Kamo River in Kyoto with the world whirling noisily around it. Like the center of a vortex, the eye in a storm of unceasing, clamorous activity, it holds its curved neck still, impervious to the cars and buses and bicycles rushing past on the surrounding banks, an embodiment of grace and fortitude of concentration as it spies the water below and waits for its prey. We’ve only just begun reading this collection, and already László Krasznahorkai’s haunting prose has submerged us in the great panta rhei of life—Heraclitus’s aphorism that everything flows in a state of continuous change.

by Callum Watts

by Callum Watts

“Battle of Algiers”, a classic 1966 film directed by Gillo Pontecorvo, seized my imagination and of my classmates as well when it was shown three years later at the Palladium in Srinagar. A teenager wearing bell-bottoms, dancing the twist, I was a Senior at Sri Pratap College, named after Maharajah Pratap Singh, a Hindu Dogra ruler of Muslim majority Kashmir.

“Battle of Algiers”, a classic 1966 film directed by Gillo Pontecorvo, seized my imagination and of my classmates as well when it was shown three years later at the Palladium in Srinagar. A teenager wearing bell-bottoms, dancing the twist, I was a Senior at Sri Pratap College, named after Maharajah Pratap Singh, a Hindu Dogra ruler of Muslim majority Kashmir. I remember as a child watching the made-for-tv movie

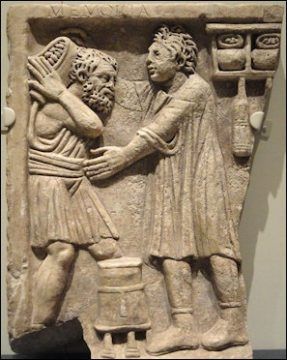

I remember as a child watching the made-for-tv movie  Whether or not a certain line of work is shameful or honorable is culturally relative, varying greatly between places and over time. Farmers, soldiers, actors, dentists, prostitutes, pirates and priests have all been respected or despised in some society or other. There are numerous reasons why certain kinds of work have been looked down on. Subjecting oneself to the will of another; doing tasks that are considered inappropriate given one’s sex, race, age, or class; doing work that is unpopular (tax collector); or deemed immoral (prostitution), or viewed as worthless (what David Graeber labelled “bullshit jobs”), or which are just very poorly paid–all these could be reasons why a kind of work is despised, even by those who do it. One of the oldest prejudices though, at least among the upper classes in many societies, is against manual labour.

Whether or not a certain line of work is shameful or honorable is culturally relative, varying greatly between places and over time. Farmers, soldiers, actors, dentists, prostitutes, pirates and priests have all been respected or despised in some society or other. There are numerous reasons why certain kinds of work have been looked down on. Subjecting oneself to the will of another; doing tasks that are considered inappropriate given one’s sex, race, age, or class; doing work that is unpopular (tax collector); or deemed immoral (prostitution), or viewed as worthless (what David Graeber labelled “bullshit jobs”), or which are just very poorly paid–all these could be reasons why a kind of work is despised, even by those who do it. One of the oldest prejudices though, at least among the upper classes in many societies, is against manual labour.