by N. Gabriel Martin

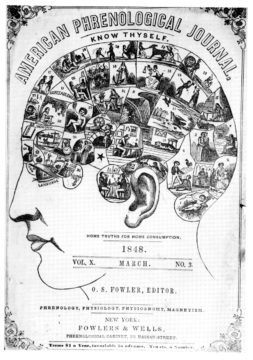

In 2017, the Nobel prize in economics attracted more attention than it usually does, when it was awarded to Richard Thaler. Articles in leading newspapers everywhere explained Thaler’s revolutionary insight: whereas economic orthodoxy was premised on the belief that humans are essentially selfish, Thaler’s work assumed that we are also stupid.

Thaler was the perfect laureate for a world trying to come to grips with Brexit and the election of Trump, even if the novelty of his theories was exaggerated. For many, faith in the decision-making ability of the public was shaken, and so was the conception of human nature underpinning liberal economics and democracy—that humans act in their own self-interest. How else could the decisions of tens of millions of Brits to tank their economy, or of more than a hundred million Americans to elect an unqualified, corrupt bigot be explained than by calling into question our ability to figure out what’s in our own best interests?

Thaler, though not all that original in this regard, has espoused a theory of human behaviour that maintains the assumption that self-interest drives our actions, but rejected the idea that we know what our interests are. This reimagining of human nature called for a reimagining of political possibilities. Thaler’s behaviourist economic view doesn’t support free market liberalism without conditions. A free market can, supposedly, be counted on to yield optimal results on the assumption that its members are able to choose what’s in their own interests, but if we are too stupid either to know what’s really in our own interests or to make the better choice most of the time, then there’s no reason to expect a free market to produce optimal outcomes. Read more »

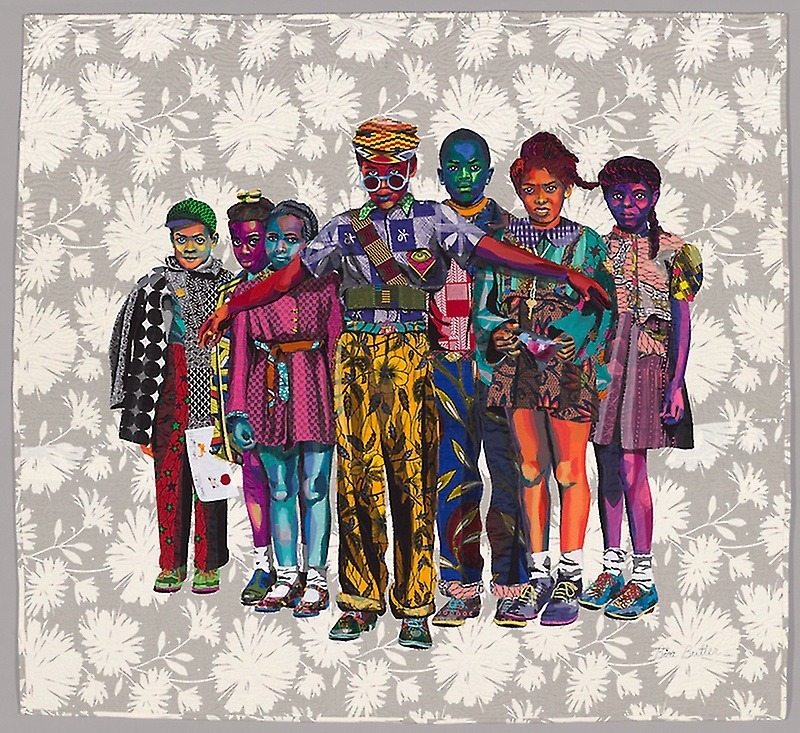

Bisa Butler. The Safety Patrol. 2018.

Bisa Butler. The Safety Patrol. 2018.

On 9 October 1990, President George H.W. Bush held a news conference about Iraqi-occupied Kuwait as the US was building an international coalition to liberate the emirate. He said: “I am very much concerned, not just about the physical dismantling but about some of the tales of brutality. It’s just unbelievable, some of the things. I mean, people on a dialysis machine cut off; babies heaved out of incubators and the incubators sent to Baghdad … It’s sickening.”

On 9 October 1990, President George H.W. Bush held a news conference about Iraqi-occupied Kuwait as the US was building an international coalition to liberate the emirate. He said: “I am very much concerned, not just about the physical dismantling but about some of the tales of brutality. It’s just unbelievable, some of the things. I mean, people on a dialysis machine cut off; babies heaved out of incubators and the incubators sent to Baghdad … It’s sickening.”

Escape. When I was a child, I read at every opportunity. If I could, I’d read on the playground; at one point, I was allowed to spend recess in the library and read there. Overall, teachers seemed unenthusiastic about the idea of a kid reading during recess. My mother, a great reader herself, used to tell me that reading was a treat, to be saved for the end of the day when all the work was done. When I was reading, I wasn’t playing with the other kids or helping out with the housework, as I should have been. But I was one of those people described by Penelope Lively, people who are “built by books, for whom books are an essential foodstuff, who could starve without.”

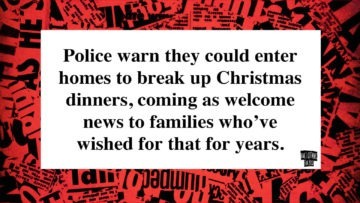

Escape. When I was a child, I read at every opportunity. If I could, I’d read on the playground; at one point, I was allowed to spend recess in the library and read there. Overall, teachers seemed unenthusiastic about the idea of a kid reading during recess. My mother, a great reader herself, used to tell me that reading was a treat, to be saved for the end of the day when all the work was done. When I was reading, I wasn’t playing with the other kids or helping out with the housework, as I should have been. But I was one of those people described by Penelope Lively, people who are “built by books, for whom books are an essential foodstuff, who could starve without.” Christmas is traditionally a time for stories – happy ones, about peace, love and birth. In this essay I’m looking at three Christmas stories, exploring what they tell us about Christmas: the First World War Christmas Truce,

Christmas is traditionally a time for stories – happy ones, about peace, love and birth. In this essay I’m looking at three Christmas stories, exploring what they tell us about Christmas: the First World War Christmas Truce,

Thorstein Veblen’s The Theory of the Leisure Class is a famous, influential, and rather peculiar book. Veblen (1857 – 1929) was a progressive-minded scholar who wrote about economics, social institutions, and culture. The Theory of the Leisure Class, which appeared in 1899, was the first of ten books that he published during his lifetime. It is the original source of the expression “conspicuous consumption,” was once required reading on many graduate syllabi, and parts of it are still regularly anthologized.

Thorstein Veblen’s The Theory of the Leisure Class is a famous, influential, and rather peculiar book. Veblen (1857 – 1929) was a progressive-minded scholar who wrote about economics, social institutions, and culture. The Theory of the Leisure Class, which appeared in 1899, was the first of ten books that he published during his lifetime. It is the original source of the expression “conspicuous consumption,” was once required reading on many graduate syllabi, and parts of it are still regularly anthologized.