by Brooks Riley

The first time I ever left home without leaving home I was twelve years old, recently back from a winter trip to Mexico. Routinely sent to bed at 8 pm (my parents were old and old-fashioned), always wondering how to fill the inevitable two hours of insomnia, I opted to return to Mexico, not as the sleepless chiquita that I was, but as the fierce guerilla chief I would become in the narrative, leading a band of outlaw Aztecs in raids against a host of injustices from base camp in a desert. No precedents existed for my leadership skills in real life, but within the carefully sculpted storyline of the daydream, I was both charismatic and respected, not merely proficient but also inspired, a warrior queen to rival any Amazon.

The first time I ever left home without leaving home I was twelve years old, recently back from a winter trip to Mexico. Routinely sent to bed at 8 pm (my parents were old and old-fashioned), always wondering how to fill the inevitable two hours of insomnia, I opted to return to Mexico, not as the sleepless chiquita that I was, but as the fierce guerilla chief I would become in the narrative, leading a band of outlaw Aztecs in raids against a host of injustices from base camp in a desert. No precedents existed for my leadership skills in real life, but within the carefully sculpted storyline of the daydream, I was both charismatic and respected, not merely proficient but also inspired, a warrior queen to rival any Amazon.

Where did this come from, this semi-androgenous role so foreign to my timid female self? I may have been feeling powerless back then, on the verge of puberty and alone in my ignorance. My daydream could just as easily have come from a twelve-year-old boy but more likely it incubated in the tomboy I sometimes was. Gender had little to do with it, though. Empowerment is what mattered, something I desperately needed, as well as a jolly exciting way to pass the time until I fell asleep.

Daydreams have served the needs of human beings since the evolution of the imagination a few million years ago. The caveman who dreamed of bagging a boar pictured an encounter in his mind and practiced his moves. Except for those with aphantasia, we can all visualize places we’ve been and people we’ve seen. This ‘inner eye’ allows us to do much more than that—to create people and places that we’ve never seen, that don’t exist, and to give them life, context, and raisons d’être. This is how fiction is born, before the first word has even hit the page.

We all indulge in daydreams, those reticules in the mind that hold our most vivid hopes in the form of mise-en-scène, endowing our bucket list with emotional nuance and narrative—however improbable the reality. With age, however, imagining a dazzling future no longer seems viable, as the scope of our hopes and desires shrink, like the law of diminishing returns. Daydreaming is eventually reduced to hardly more than an imagined walk in the park when you’re stuck at home. Much of my bucket list has been accomplished, in sometimes surprising ways. My life has been eclectic, peripatetic, unexpected, and gratifying. I’ve been places, done things. What more could there be to dream about? Read more »

In the summer of 2000, after completing my bachelor’s degree in engineering, I had to decide where to go next. I could either take up a job offer at a motorcycle manufacturing plant in south India, or I could, like many of my college friends, head to a university in the United States. Most of my friends had assistantships and tuition waivers. I had been admitted to a couple of state universities but did not have any financial support. Out a feeling that if I stayed back in India, I’d be ‘left behind’ – whatever that meant: it was only a trick of the mind, left unexamined – I took a risk, and decided to try graduate school at Arizona State University. I hoped that funding would work out somehow.

In the summer of 2000, after completing my bachelor’s degree in engineering, I had to decide where to go next. I could either take up a job offer at a motorcycle manufacturing plant in south India, or I could, like many of my college friends, head to a university in the United States. Most of my friends had assistantships and tuition waivers. I had been admitted to a couple of state universities but did not have any financial support. Out a feeling that if I stayed back in India, I’d be ‘left behind’ – whatever that meant: it was only a trick of the mind, left unexamined – I took a risk, and decided to try graduate school at Arizona State University. I hoped that funding would work out somehow. One of the most interesting and memorable characters in sci-fi films is the

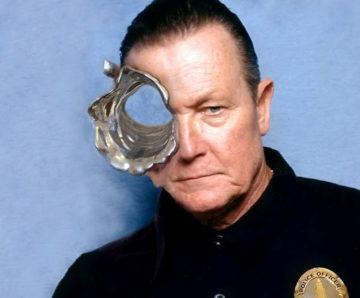

One of the most interesting and memorable characters in sci-fi films is the

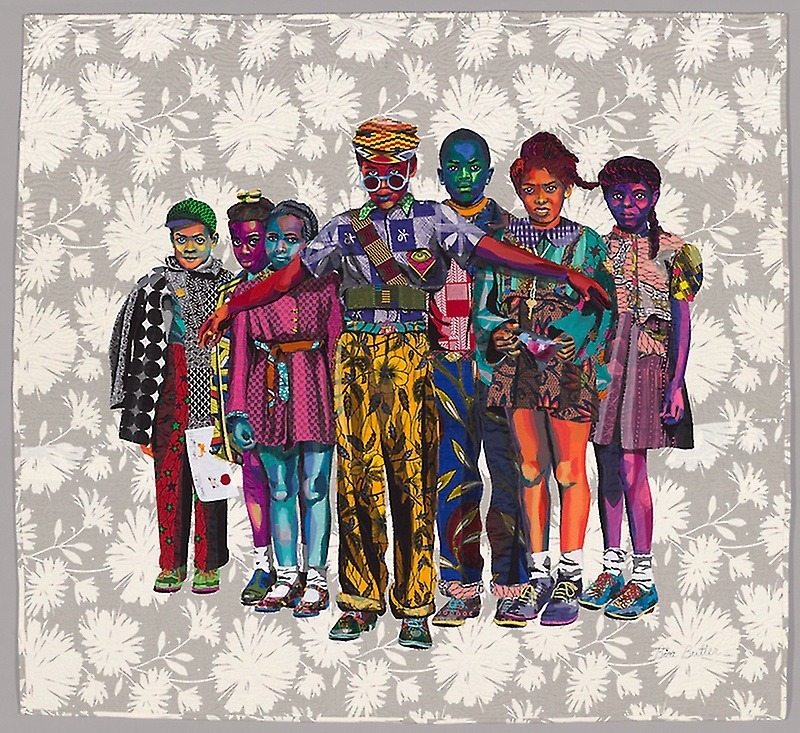

Bisa Butler. The Safety Patrol. 2018.

Bisa Butler. The Safety Patrol. 2018.

On 9 October 1990, President George H.W. Bush held a news conference about Iraqi-occupied Kuwait as the US was building an international coalition to liberate the emirate. He said: “I am very much concerned, not just about the physical dismantling but about some of the tales of brutality. It’s just unbelievable, some of the things. I mean, people on a dialysis machine cut off; babies heaved out of incubators and the incubators sent to Baghdad … It’s sickening.”

On 9 October 1990, President George H.W. Bush held a news conference about Iraqi-occupied Kuwait as the US was building an international coalition to liberate the emirate. He said: “I am very much concerned, not just about the physical dismantling but about some of the tales of brutality. It’s just unbelievable, some of the things. I mean, people on a dialysis machine cut off; babies heaved out of incubators and the incubators sent to Baghdad … It’s sickening.”

Escape. When I was a child, I read at every opportunity. If I could, I’d read on the playground; at one point, I was allowed to spend recess in the library and read there. Overall, teachers seemed unenthusiastic about the idea of a kid reading during recess. My mother, a great reader herself, used to tell me that reading was a treat, to be saved for the end of the day when all the work was done. When I was reading, I wasn’t playing with the other kids or helping out with the housework, as I should have been. But I was one of those people described by Penelope Lively, people who are “built by books, for whom books are an essential foodstuff, who could starve without.”

Escape. When I was a child, I read at every opportunity. If I could, I’d read on the playground; at one point, I was allowed to spend recess in the library and read there. Overall, teachers seemed unenthusiastic about the idea of a kid reading during recess. My mother, a great reader herself, used to tell me that reading was a treat, to be saved for the end of the day when all the work was done. When I was reading, I wasn’t playing with the other kids or helping out with the housework, as I should have been. But I was one of those people described by Penelope Lively, people who are “built by books, for whom books are an essential foodstuff, who could starve without.” Christmas is traditionally a time for stories – happy ones, about peace, love and birth. In this essay I’m looking at three Christmas stories, exploring what they tell us about Christmas: the First World War Christmas Truce,

Christmas is traditionally a time for stories – happy ones, about peace, love and birth. In this essay I’m looking at three Christmas stories, exploring what they tell us about Christmas: the First World War Christmas Truce,