by Varun Gauri

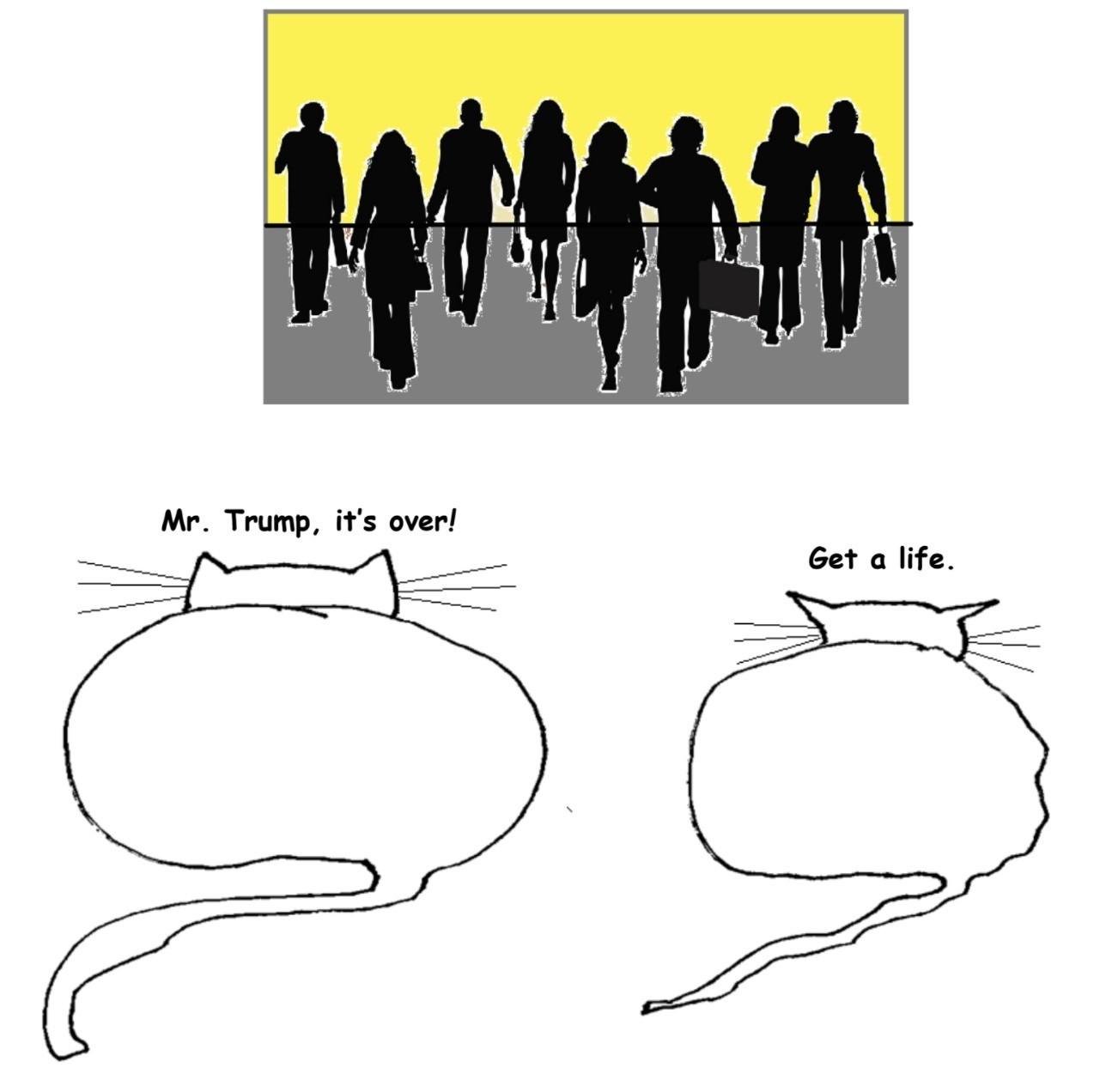

The spirit of gift exchange animates democracy. In exchange for letting you control government, giving you power over the security forces, the common treasure, and the agencies and civil service — which is power over me — you agree to grant me those same powers — and power over you — in the future. I am then entitled to control government and its coercive powers in exchange for agreeing to transfer those powers back to you, or your representatives, when the time comes.

Aristotle emphasized this, arguing that in political regimes where citizens are more or less equal, the citizens alternate governing, “ruling and being ruled in turn.” Rawls believed this notion of reciprocity in democratic societies is widely relevant across a range of social and economic practices, including taxation: Because society should be seen “as a fair system of cooperation over time,” not only public offices but the common surplus should be divided in a way that acknowledges mutual contributions over time. My firm profited from those highways and airports and bridges that others paid for and built; now I pay it forward, in the form of taxes.

This principle of reciprocity applies not only to taxation and to ceding control of government — conceding after an election loss — but to forbearance in the exercise of power. When I’m in power, the principle requires me to appreciate that the security forces, the common treasure, and the civil service are not mine to control forever. One day they will be yours. So I shouldn’t break or repurpose them in a way that leaves them not useful to you, for your objectives, when it becomes your turn to rule. It’s hard to specify the point at which the pursuit of ordinary policy objectives amounts to breaking or repurposing institutions and agencies, but the line certainly exists. An outgoing administration repurposing the civil service by installing loyalists, or by raiding the treasure, is, after a certain point, normatively equivalent to an executive embezzling funds from a business partner (or worse). Read more »

The first time I ever left home without leaving home I was twelve years old, recently back from a winter trip to Mexico. Routinely sent to bed at 8 pm (my parents were old and old-fashioned), always wondering how to fill the inevitable two hours of insomnia, I opted to return to Mexico, not as the sleepless chiquita that I was, but as the fierce guerilla chief I would become in the narrative, leading a band of outlaw Aztecs in raids against a host of injustices from base camp in a desert. No precedents existed for my leadership skills in real life, but within the carefully sculpted storyline of the daydream, I was both charismatic and respected, not merely proficient but also inspired, a warrior queen to rival any Amazon.

The first time I ever left home without leaving home I was twelve years old, recently back from a winter trip to Mexico. Routinely sent to bed at 8 pm (my parents were old and old-fashioned), always wondering how to fill the inevitable two hours of insomnia, I opted to return to Mexico, not as the sleepless chiquita that I was, but as the fierce guerilla chief I would become in the narrative, leading a band of outlaw Aztecs in raids against a host of injustices from base camp in a desert. No precedents existed for my leadership skills in real life, but within the carefully sculpted storyline of the daydream, I was both charismatic and respected, not merely proficient but also inspired, a warrior queen to rival any Amazon. In the summer of 2000, after completing my bachelor’s degree in engineering, I had to decide where to go next. I could either take up a job offer at a motorcycle manufacturing plant in south India, or I could, like many of my college friends, head to a university in the United States. Most of my friends had assistantships and tuition waivers. I had been admitted to a couple of state universities but did not have any financial support. Out a feeling that if I stayed back in India, I’d be ‘left behind’ – whatever that meant: it was only a trick of the mind, left unexamined – I took a risk, and decided to try graduate school at Arizona State University. I hoped that funding would work out somehow.

In the summer of 2000, after completing my bachelor’s degree in engineering, I had to decide where to go next. I could either take up a job offer at a motorcycle manufacturing plant in south India, or I could, like many of my college friends, head to a university in the United States. Most of my friends had assistantships and tuition waivers. I had been admitted to a couple of state universities but did not have any financial support. Out a feeling that if I stayed back in India, I’d be ‘left behind’ – whatever that meant: it was only a trick of the mind, left unexamined – I took a risk, and decided to try graduate school at Arizona State University. I hoped that funding would work out somehow. One of the most interesting and memorable characters in sci-fi films is the

One of the most interesting and memorable characters in sci-fi films is the

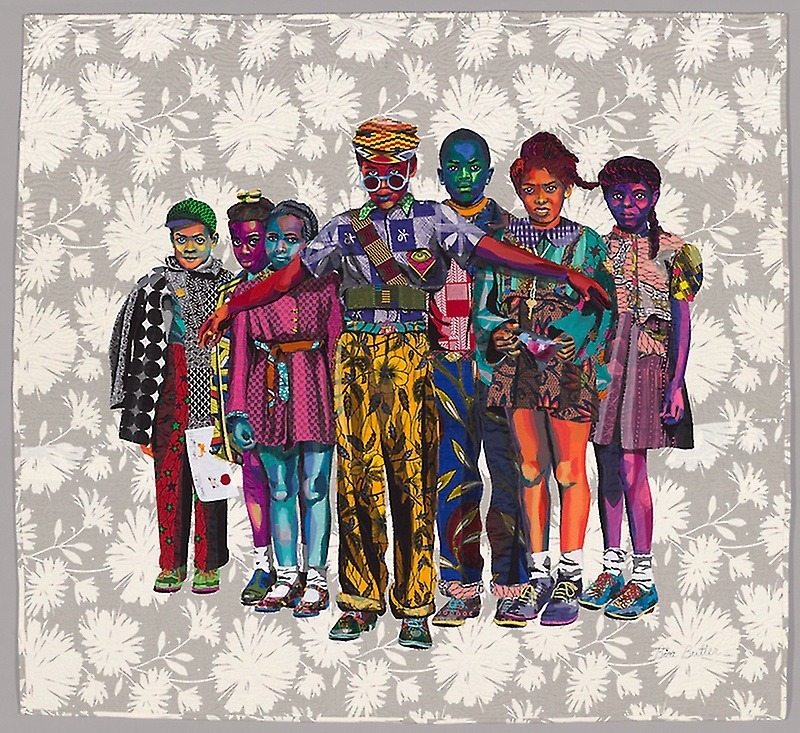

Bisa Butler. The Safety Patrol. 2018.

Bisa Butler. The Safety Patrol. 2018.

On 9 October 1990, President George H.W. Bush held a news conference about Iraqi-occupied Kuwait as the US was building an international coalition to liberate the emirate. He said: “I am very much concerned, not just about the physical dismantling but about some of the tales of brutality. It’s just unbelievable, some of the things. I mean, people on a dialysis machine cut off; babies heaved out of incubators and the incubators sent to Baghdad … It’s sickening.”

On 9 October 1990, President George H.W. Bush held a news conference about Iraqi-occupied Kuwait as the US was building an international coalition to liberate the emirate. He said: “I am very much concerned, not just about the physical dismantling but about some of the tales of brutality. It’s just unbelievable, some of the things. I mean, people on a dialysis machine cut off; babies heaved out of incubators and the incubators sent to Baghdad … It’s sickening.”

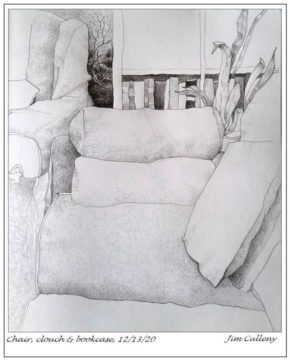

Escape. When I was a child, I read at every opportunity. If I could, I’d read on the playground; at one point, I was allowed to spend recess in the library and read there. Overall, teachers seemed unenthusiastic about the idea of a kid reading during recess. My mother, a great reader herself, used to tell me that reading was a treat, to be saved for the end of the day when all the work was done. When I was reading, I wasn’t playing with the other kids or helping out with the housework, as I should have been. But I was one of those people described by Penelope Lively, people who are “built by books, for whom books are an essential foodstuff, who could starve without.”

Escape. When I was a child, I read at every opportunity. If I could, I’d read on the playground; at one point, I was allowed to spend recess in the library and read there. Overall, teachers seemed unenthusiastic about the idea of a kid reading during recess. My mother, a great reader herself, used to tell me that reading was a treat, to be saved for the end of the day when all the work was done. When I was reading, I wasn’t playing with the other kids or helping out with the housework, as I should have been. But I was one of those people described by Penelope Lively, people who are “built by books, for whom books are an essential foodstuff, who could starve without.” Christmas is traditionally a time for stories – happy ones, about peace, love and birth. In this essay I’m looking at three Christmas stories, exploring what they tell us about Christmas: the First World War Christmas Truce,

Christmas is traditionally a time for stories – happy ones, about peace, love and birth. In this essay I’m looking at three Christmas stories, exploring what they tell us about Christmas: the First World War Christmas Truce,