by Mike O’Brien

There’s a concept in education, particularly science education, called “lies-to-children”. It roughly means this: some matters are so complicated that they cannot be clearly understood when accurately presented. So, if you want a naive audience (“children”) to eventually understand how these complex matters actually work, you need to prepare their minds with inaccurate but helpfully simplified analogies, which are discarded and replaced by ever more complicated and accurate analogies, until they are finally ready to understand the most complicated and accurate version of the truth presently available. A concrete example is teaching Newtonian physics in high school, then telling university physics students arriving for their first day of class that everything they’ve been taught is a lie (and everything they’re about to learn is also a lie, but necessarily so).

The concept of rights, both human and non-human, is like this. It is different from concepts in physics or chemistry in that it is fundamentally prescriptive rather than descriptive, but operates exactly like “lies” in scientific education in that the simplicity and certainty of false portrayals serve to accomplish a useful end. In the case of science education, that end is a mental “formatting” that prepares the student for incrementally more complicated pictures of reality. In the case of moral advocacy, the end is to introduce a predicate that can be attached to objects in moral calculation, allowing moral discussions to proceed in a descriptive, concrete mode rather than a prescriptive, contentious one.

Do rights exist? That strikes me as a nonsensical question. Is there a moral state of affairs that is usefully analogised by “rights” discourse? Now you’re talking. I’m not sure that there is, or that any objective state of moral affairs can be objectively shown to obtain, but at least rights talk seems to be an activity that morally interested, language-using beings can engage in with useful results. We can talk about how people have rights, and what obligations those rights impose on how people are treated by others. We can talk about how animals have rights, and what obligations those rights impose on how animals are treated. We can even talk about according rights to trees, mountains, and legally incorporated businesses, if we want to. But the trees don’t know they have rights, nor do the mountains, nor do the animals. And, given the dismal state of moral and civic education in many places, nor do many people. If they don’t think of themselves as having rights (or, furthermore, lack any clear concept of legal or moral right), and don’t experience any special treatment or status as rights-holders, what does it matter if some philosopher or judge believes them to have rights? Read more »

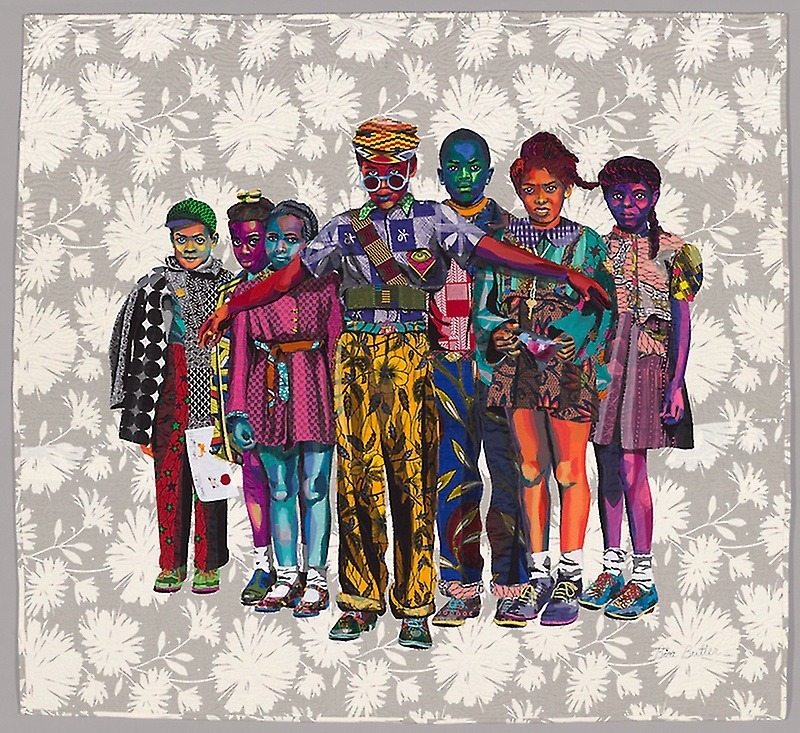

Bisa Butler. The Safety Patrol. 2018.

Bisa Butler. The Safety Patrol. 2018.

On 9 October 1990, President George H.W. Bush held a news conference about Iraqi-occupied Kuwait as the US was building an international coalition to liberate the emirate. He said: “I am very much concerned, not just about the physical dismantling but about some of the tales of brutality. It’s just unbelievable, some of the things. I mean, people on a dialysis machine cut off; babies heaved out of incubators and the incubators sent to Baghdad … It’s sickening.”

On 9 October 1990, President George H.W. Bush held a news conference about Iraqi-occupied Kuwait as the US was building an international coalition to liberate the emirate. He said: “I am very much concerned, not just about the physical dismantling but about some of the tales of brutality. It’s just unbelievable, some of the things. I mean, people on a dialysis machine cut off; babies heaved out of incubators and the incubators sent to Baghdad … It’s sickening.”

Escape. When I was a child, I read at every opportunity. If I could, I’d read on the playground; at one point, I was allowed to spend recess in the library and read there. Overall, teachers seemed unenthusiastic about the idea of a kid reading during recess. My mother, a great reader herself, used to tell me that reading was a treat, to be saved for the end of the day when all the work was done. When I was reading, I wasn’t playing with the other kids or helping out with the housework, as I should have been. But I was one of those people described by Penelope Lively, people who are “built by books, for whom books are an essential foodstuff, who could starve without.”

Escape. When I was a child, I read at every opportunity. If I could, I’d read on the playground; at one point, I was allowed to spend recess in the library and read there. Overall, teachers seemed unenthusiastic about the idea of a kid reading during recess. My mother, a great reader herself, used to tell me that reading was a treat, to be saved for the end of the day when all the work was done. When I was reading, I wasn’t playing with the other kids or helping out with the housework, as I should have been. But I was one of those people described by Penelope Lively, people who are “built by books, for whom books are an essential foodstuff, who could starve without.” Christmas is traditionally a time for stories – happy ones, about peace, love and birth. In this essay I’m looking at three Christmas stories, exploring what they tell us about Christmas: the First World War Christmas Truce,

Christmas is traditionally a time for stories – happy ones, about peace, love and birth. In this essay I’m looking at three Christmas stories, exploring what they tell us about Christmas: the First World War Christmas Truce,