by Rafaël Newman

By a quirk of the calendars, Passover, the annual commemoration of the flight from bondage, is precisely coterminous this year with Academic Travel. This latter, a twice-yearly feature of the university in Switzerland at which I am guest teaching this semester, is that institution’s “signature program”: a week-and-a-half course, typically offered in a location outside Switzerland, focusing on a topic arising from that site. A chance for students to read a city, as it were, like a text.

This year, for obvious reasons, Academic Travel has been canceled – or rather, radically curtailed, with students in the university’s home city of Lugano, in the canton of Ticino, required to produce negative virus tests before traveling merely to other parts of Switzerland, all reachable by train and bus, instead of, as in years past, flying to more appealingly distant locations, such as Poland, Greece, Turkey, and points further afield. For now even relatively nearby destinations, such as Italy or France, have been ruled out by the authorities, shrinking the offerings for the spring semester’s Academic Travel to the familiar hotspots of the Swiss grand tour – Lucerne, Zermatt, Geneva – which are then to serve as makeshift staging grounds for courses on topics in environmental science, history, economics, and the like.

And thus the Jewish festival of Passover, a holiday explicitly celebrating escape from plague, freedom of movement, and the crossing of borders, falls during a period in which students, under threat of contagion, are subject to personal restriction, and are confined within the borders of their current national location.

The convergence of a traditional commemoration of ancient release from bondage with a frustrated travel project in the present is especially poignant for me, perhaps yet more so for my students, since the course I am teaching them in regular session, on “Jewish Writing in German”, involves among other things the reading of three texts that treat themes of migration from a variety of perspectives, and in each of which a Passover scene figures centrally. Read more »

I discovered my ideal radio station by accident.

I discovered my ideal radio station by accident.

I’ll return to that second crack once we’ve explored the first one. But why do that at all? Does free will matter to anyone but a couple of bickering philosophers? Of course it does! Sam Harris noted in his recent

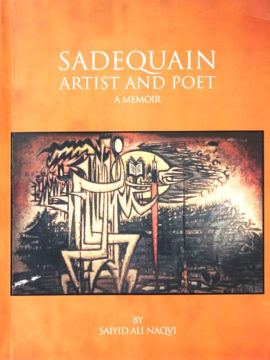

I’ll return to that second crack once we’ve explored the first one. But why do that at all? Does free will matter to anyone but a couple of bickering philosophers? Of course it does! Sam Harris noted in his recent  “Sadequain!” The very name is like a magic word that triggers a tumult of images in the mind. Arguably, no Pakistani artist has elicited more admiration, evoked more passion, and received more adulation than Saiyid Sadquain Ahmad Naqvi, the subject – and really, the hero – of the book “Sadequain: Artist and Poet – A Memoir” by Saiyid Ali Naqvi. In the world of art, be it painting, music, or literature, it is the pinnacle of achievement to be recognized by a single name – to need no further introduction. And rare indeed is the artist who achieves this distinction in his or her own life, as Sadequain did remarkably early in his career as an artist. And this delightful, beautiful, and insightful book shows why. Beginning with the earliest and formative years of Sadequain when he was not yet a legend, it takes the reader systematically through all stages of his life and his growth as an artist, laying bare both the immense determination and the perpetual restlessness of the artist’s genius.

“Sadequain!” The very name is like a magic word that triggers a tumult of images in the mind. Arguably, no Pakistani artist has elicited more admiration, evoked more passion, and received more adulation than Saiyid Sadquain Ahmad Naqvi, the subject – and really, the hero – of the book “Sadequain: Artist and Poet – A Memoir” by Saiyid Ali Naqvi. In the world of art, be it painting, music, or literature, it is the pinnacle of achievement to be recognized by a single name – to need no further introduction. And rare indeed is the artist who achieves this distinction in his or her own life, as Sadequain did remarkably early in his career as an artist. And this delightful, beautiful, and insightful book shows why. Beginning with the earliest and formative years of Sadequain when he was not yet a legend, it takes the reader systematically through all stages of his life and his growth as an artist, laying bare both the immense determination and the perpetual restlessness of the artist’s genius.

The world we live in is changing, and our politics must change with it. We are in what has been called the ‘anthropocene’: the period in which human activity is threatening the ecosystem on which we all depend. Catastrophic climate change threatens our very survival. Yet our political class seems unable to take the necessary steps to avert it. Add to that the familiar and pressing problems of massive inequality, exploitation, systemic racism and job insecurity due to automation and the relocation of production to cheaper labour markets, and we have a truly global and multidimensional set of problems. It is one that our political masters seem unable to properly confront. Yet confront them they, and we, must. Such is the scale of the problem, the political order needs wholesale change, rather than the small, incremental reforms we have been taught are all that are practicable or desirable. And change, whether we like it or not is coming anyway: between authoritarian national conservative regimes, which with all the inequality, xenophobia, or that of a democratic, green post-capitalism. The thing that won’t survive is liberalism.

The world we live in is changing, and our politics must change with it. We are in what has been called the ‘anthropocene’: the period in which human activity is threatening the ecosystem on which we all depend. Catastrophic climate change threatens our very survival. Yet our political class seems unable to take the necessary steps to avert it. Add to that the familiar and pressing problems of massive inequality, exploitation, systemic racism and job insecurity due to automation and the relocation of production to cheaper labour markets, and we have a truly global and multidimensional set of problems. It is one that our political masters seem unable to properly confront. Yet confront them they, and we, must. Such is the scale of the problem, the political order needs wholesale change, rather than the small, incremental reforms we have been taught are all that are practicable or desirable. And change, whether we like it or not is coming anyway: between authoritarian national conservative regimes, which with all the inequality, xenophobia, or that of a democratic, green post-capitalism. The thing that won’t survive is liberalism.

Over recent times, many books have been published with the aim of writing women into history and crediting them for the achievements they have made to the benefit of humanity more broadly. Janice P. Nimura’s The Doctors Blackwell is in that genre of women’s history and she effectively narrates the biographies of the first two remarkable women to study and practice medicine in the United States: Elizabeth Blackwell and her younger sister, Emily.

Over recent times, many books have been published with the aim of writing women into history and crediting them for the achievements they have made to the benefit of humanity more broadly. Janice P. Nimura’s The Doctors Blackwell is in that genre of women’s history and she effectively narrates the biographies of the first two remarkable women to study and practice medicine in the United States: Elizabeth Blackwell and her younger sister, Emily. Cynthia, let me begin by asking you to describe your path to the book—a double path that led you to Joseph Brodsky and to George L. Kline.

Cynthia, let me begin by asking you to describe your path to the book—a double path that led you to Joseph Brodsky and to George L. Kline.