by Jonathan Kujawa

Every institution has its founding myths. In mathematics, one of ours is that mathematical truths are unassailable, universal, and eternal. And that any intelligent being can discover and verify those same truths for themself.

This is why movie aliens who want to communicate with us usually use math [1]. The cornerstone of this myth is that mathematicians give airtight logical arguments for their truths. After all, Pythagoras knew his eponymous theorem 2500 years ago and it’s as true as it ever was. And it was equally true in Mesopotamia 3500 years ago and in China and India 2000+ years ago.

The idea of a “mathematical proof” is what makes math, math.

This semester I am teaching our introduction to mathematical proofs course. The not-so-secret purpose of the class is to help students transition from being mathematical computers to being mathematical creators. The students learn what it means to think mathematically. This includes how to take vague and ill-framed questions and turn them into mathematics, how to creatively solve those problems, and how to communicate those solutions in written and verbal form.

A huge part of the course is teaching the students what it means to give a valid proof. They learn about direct proofs (a direct logical march to the desired result), proofs by contradiction (if the desired result weren’t true, then one is forced to a logical impossibility), proofs by induction (using a recursive loop to verify the desired result), and more. They also learn some of the common pitfalls like pre-supposing the desired result and thereby begging the question.

The topics of the course are basic number theory, set theory, logic, functions, and the like, but the real content is how to read and write proofs. Read more »

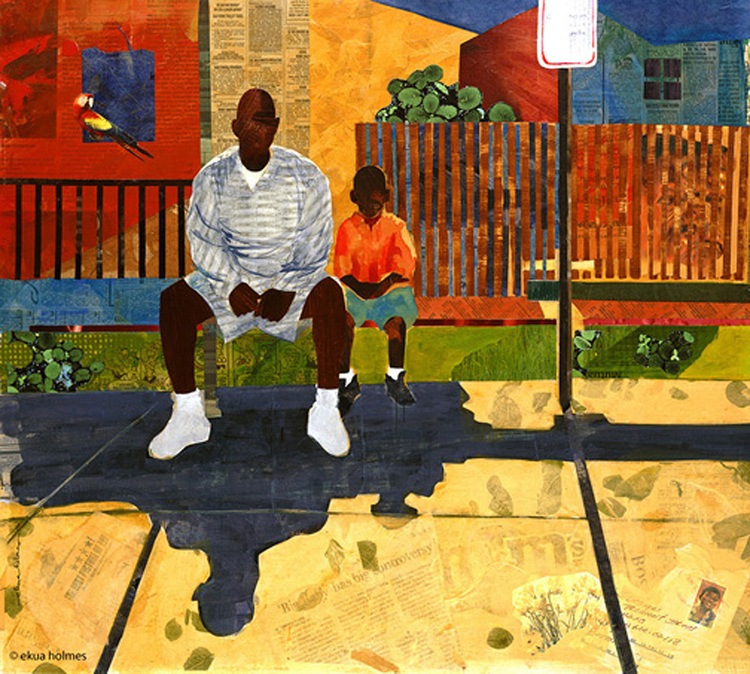

Ekua Holmes. There’s No Place Like Home.

Ekua Holmes. There’s No Place Like Home.

Of all the secondary discomforts imposed by the pandemic, the most treacherous may be inertia. Life, interrupted, can be characterized as an absence of movement, like a stream that stops running, stagnating as the surface begins to cloud with algae and other still-standing detritus. Inertia that stems from the current situation can quelch any creative impulse. Even cinema, that paradigm of life in motion—the moving picture—isn’t much help if we expect our own lives to keep moving as well as movies do. They don’t, at least not right now.

Of all the secondary discomforts imposed by the pandemic, the most treacherous may be inertia. Life, interrupted, can be characterized as an absence of movement, like a stream that stops running, stagnating as the surface begins to cloud with algae and other still-standing detritus. Inertia that stems from the current situation can quelch any creative impulse. Even cinema, that paradigm of life in motion—the moving picture—isn’t much help if we expect our own lives to keep moving as well as movies do. They don’t, at least not right now.

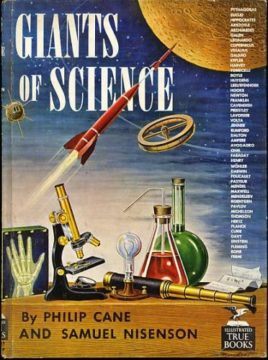

In many ways, the story of my life is the story of books that I have read and loved. Books haven’t just shaped and dictated what I know and think about the world but they have been an emotional anchor, as rock solid as a real ship’s anchor in stormy seas. As the son of two professors with a voracious appetite for reading, it was entirely unsurprising that I acquired a love of reading and knowledge very early on. The Indian city of Pune that I grew up in was sometimes referred to as the “Oxford of the East” for its emphasis on education, museums and libraries, so a love of learning came easy when you grew up there. For 35 years until their mandatory retirement, my parents both taught at Fergusson College in Pune.

In many ways, the story of my life is the story of books that I have read and loved. Books haven’t just shaped and dictated what I know and think about the world but they have been an emotional anchor, as rock solid as a real ship’s anchor in stormy seas. As the son of two professors with a voracious appetite for reading, it was entirely unsurprising that I acquired a love of reading and knowledge very early on. The Indian city of Pune that I grew up in was sometimes referred to as the “Oxford of the East” for its emphasis on education, museums and libraries, so a love of learning came easy when you grew up there. For 35 years until their mandatory retirement, my parents both taught at Fergusson College in Pune.

At the 100th anniversary of John Rawls’ birth back in February, some of the most generous op-eds, whilst celebrating the brilliance of his thought, lamented the torpor of his impact. ‘Rawls studies’ are by no means the totality of political philosophy, but they are one of its most significant strands, and his approach has been dominant for the past 50 years. I’m an admirer of political philosophy, having happily spent much time and energy studying it, specifically looking at theories of deliberative democracy, an area with important connections to Rawls’ thought. That political philosophy does not have much to say that is of direct practical concern does not bother me, the sense that it is not just uninfluential, but is disconnected from the reality of the present moment does though.

At the 100th anniversary of John Rawls’ birth back in February, some of the most generous op-eds, whilst celebrating the brilliance of his thought, lamented the torpor of his impact. ‘Rawls studies’ are by no means the totality of political philosophy, but they are one of its most significant strands, and his approach has been dominant for the past 50 years. I’m an admirer of political philosophy, having happily spent much time and energy studying it, specifically looking at theories of deliberative democracy, an area with important connections to Rawls’ thought. That political philosophy does not have much to say that is of direct practical concern does not bother me, the sense that it is not just uninfluential, but is disconnected from the reality of the present moment does though. Anderson Ambroise. Rubble Sculpture.

Anderson Ambroise. Rubble Sculpture.