by Omar Baig

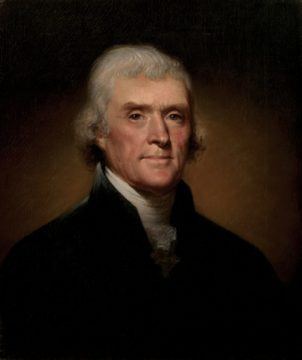

In the Fall of 1959, Cora Diamond left a computer programming job at IBM to enroll at the University of Oxford’s philosophy department: despite earning a Bachelor’s in Mathematics from Swarthmore College and an incomplete Master’s in Economics from MIT. After finishing a B. Phil in 1961, Diamond spent the next decade teaching at flagship universities across the UK: at Swansea (Wales), Sussex (England), and Aberdeen (Scotland). Diamond returned to America as a visiting lecturer at the University of Virginia’s philosophy department, from 1969 to 1970. They hired her as a full-time Associate Professor in 1971, making Diamond one of the few women to teach at UVa’s main College of Arts and Sciences—coinciding with the first incoming class of 450 undergraduate women.

From 1973 to 1976, Diamond posthumously compiled, edited, and published Ludwig Wittgenstein’s Lectures on the Foundations of Mathematics (1976), quickly becoming a pre-eminent scholar of New Wittgenstein, or ordinary language philosophy. In just a few years, Diamond branched out from this drier, more technical work—by building on two of Wittgenstein’s most prominent students, Elizabeth Anscombe and Iris Murdoch—towards her own non-moralistic and anti-essentialist approach to ethics. “Eating Meat and Eating People” (1978), for example, starts with a peculiar, yet indelible fact about the relatively few animals that humans deem edible vs. all the other species deemed non-edible. The near-universal taboo against human cannibalism means, “We do not eat our dead,” even in cases of accidental death or consensual cannibalism. Yet, why do these cases normalize the eating and salvaging of what may otherwise be first-class flesh? Read more »

Santiniketan in my childhood used to attract a lot of foreign scholars, artists and students, which was a boon to a young stamp-collector like me. Every day the sorting at the small post office was completed by mid-morning and many of the residents used to come and collect their mail themselves. I, along with a couple of other children, used to wait there for the foreigners to collect their mail. As soon as one was spotted, we used to scream “Stamp! Stamp!”; they obliged us by tearing off the stamps in their envelopes. Soon I had a thick album of foreign stamps. I used to linger wistfully over every stamp and imagined things about those distant foreign lands. (I remember Swiss stamps said only ‘Helvetia’ on them, which I could never find in the only world map I had at home).

Santiniketan in my childhood used to attract a lot of foreign scholars, artists and students, which was a boon to a young stamp-collector like me. Every day the sorting at the small post office was completed by mid-morning and many of the residents used to come and collect their mail themselves. I, along with a couple of other children, used to wait there for the foreigners to collect their mail. As soon as one was spotted, we used to scream “Stamp! Stamp!”; they obliged us by tearing off the stamps in their envelopes. Soon I had a thick album of foreign stamps. I used to linger wistfully over every stamp and imagined things about those distant foreign lands. (I remember Swiss stamps said only ‘Helvetia’ on them, which I could never find in the only world map I had at home).

Billions of people around the world continue to live in great poverty. What is the responsibility of rich countries to address this?

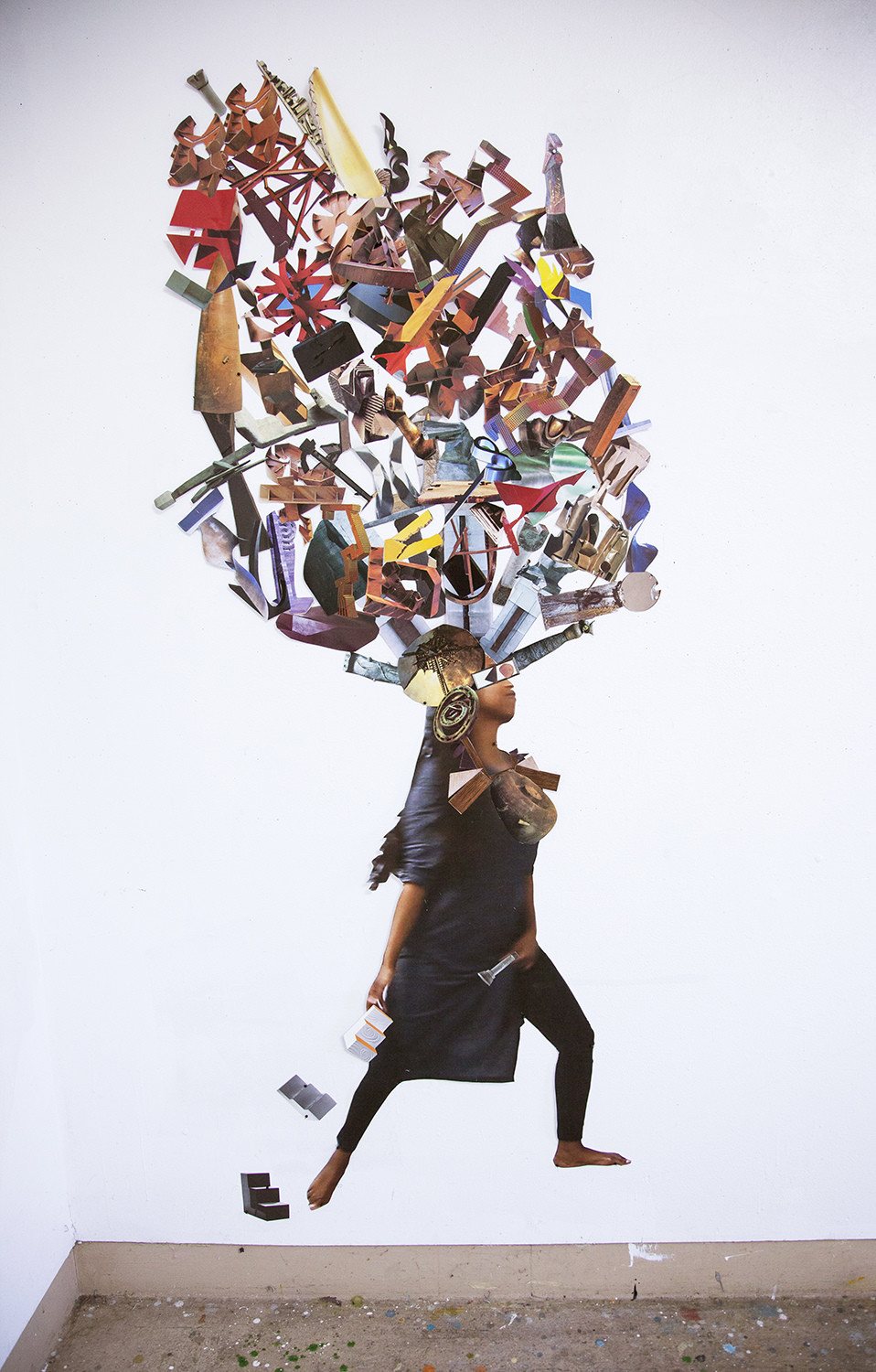

Billions of people around the world continue to live in great poverty. What is the responsibility of rich countries to address this? The best thing about a painting is that no two people ever paint the same one. They could be sitting in the same garden, staring at the same tree in the same light, poking the same brush in the same pigments, but in the end none of that matters. The two hypothetical tree-paintings are going to turn out different, because the two hypothetical painters are different also.

The best thing about a painting is that no two people ever paint the same one. They could be sitting in the same garden, staring at the same tree in the same light, poking the same brush in the same pigments, but in the end none of that matters. The two hypothetical tree-paintings are going to turn out different, because the two hypothetical painters are different also. The work ethic is deeply ingrained in much of modern society, both Eastern and Western, and there are many forces making sure that this remains the case. Parents, teachers, coaches, politicians, employers, and many other shapers of souls or makers of opinion constantly repeat the idea that hard work is the key to success–in any particular endeavour, or in life itself. It would be a brave graduation speaker who seriously urged their young listeners to embrace idleness. (I did once hear Ariana Huffington advise Smith College graduates to “sleep their way to the top,” but she essentially meant that they should avoid burn out by ensuring that they get sufficient rest.)

The work ethic is deeply ingrained in much of modern society, both Eastern and Western, and there are many forces making sure that this remains the case. Parents, teachers, coaches, politicians, employers, and many other shapers of souls or makers of opinion constantly repeat the idea that hard work is the key to success–in any particular endeavour, or in life itself. It would be a brave graduation speaker who seriously urged their young listeners to embrace idleness. (I did once hear Ariana Huffington advise Smith College graduates to “sleep their way to the top,” but she essentially meant that they should avoid burn out by ensuring that they get sufficient rest.)

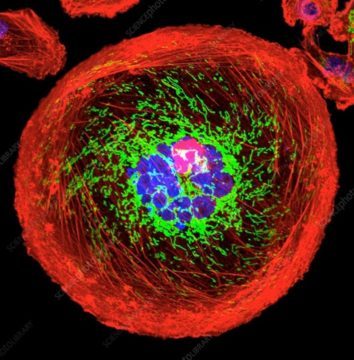

Ninety percent cancers diagnosed at Stage I are cured. Ninety percent diagnosed at Stage IV are not. Early detection saves lives. Unfortunately, more than a third of the patients already have advanced disease at diagnosis. Most die. We can, and must, do better. But why be satisfied with diagnosing Stage I disease that also requires disfiguring and invasive treatments? Why not aim higher and track down the origin of cancer? The First Cell. To do so, cancer must be caught at birth. This remains a challenging problem for researchers.

Ninety percent cancers diagnosed at Stage I are cured. Ninety percent diagnosed at Stage IV are not. Early detection saves lives. Unfortunately, more than a third of the patients already have advanced disease at diagnosis. Most die. We can, and must, do better. But why be satisfied with diagnosing Stage I disease that also requires disfiguring and invasive treatments? Why not aim higher and track down the origin of cancer? The First Cell. To do so, cancer must be caught at birth. This remains a challenging problem for researchers. In the beginning, the god of the

In the beginning, the god of the

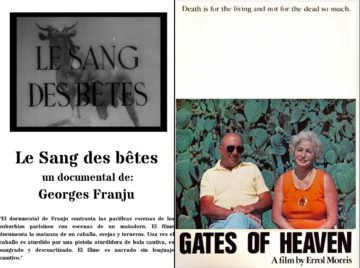

Blood of the Beasts (Le sang des bêtes)

Blood of the Beasts (Le sang des bêtes)