by Ashutosh Jogalekar

From 8th grade to 11th grade, I was taught mathematics by a teacher who was a tyrant. A brilliant man who left a lucrative engineering career to teach high school, he clearly was dedicated to teaching the subject. But his dedication took the form of catering to the brightest students in the class and mocking the rest. Since I was not among the brightest students, I was often the object of his ridicule. I was deeply interested in music by this point and sometimes came in late for class because I was held up in music practice; when this happened he used to mercilessly taunt me in front of everyone else and tell me that I should probably drop out of school and start a band. Sometimes he used to refuse me entry to the class. At an age where peer validation means much, this was devastating. Hatred of the man led to hatred of math and I turned into a rebel, not caring about the subject. I liked the abstract aspects of math but just wouldn’t do the problems, seeing it as an act of rebellion

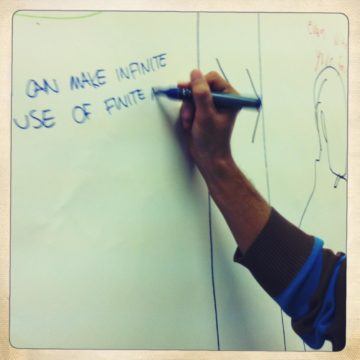

The old joke goes that the world can be divided into three kinds of people – those who can count and those who can’t. Like many jokes this one has a shred of truth in it because math does seem to impose binary divisions on us. Most of us put up with it because it’s useful to us to various extents in our professions, be it accounting, biology or economics. Some of us love it. A select few are blessed with great natural ability and passion for the subject. The rest of us are not just bad at but are often proud of our mathematical deficiency. How often have we come across people or caught ourselves joking that we were always “bad at math”? The result of this attitude – as indicated by any reading of the pandemic news these days for instance – is that we live in a largely mathematically illiterate society which is both bad at and distasteful of numbers and statistics. But it doesn’t have to be that way. Read more »

On May 31st, 2021, I sent an email to John Pawelek, Senior Research Scientist at Yale University, requesting a zoom meeting. When a week went by without a response, I decided to call. Searching for his number, I came across his Obituary instead. John Pawelek died on May 31st, 2021. Alas, I missed my chance to speak to a knowledgeable and accomplished scientist.

On May 31st, 2021, I sent an email to John Pawelek, Senior Research Scientist at Yale University, requesting a zoom meeting. When a week went by without a response, I decided to call. Searching for his number, I came across his Obituary instead. John Pawelek died on May 31st, 2021. Alas, I missed my chance to speak to a knowledgeable and accomplished scientist. This year marks the 200th anniversary of Napoleon Bonaparte’s death in exile on the island of St Helena. And it was 206 years ago last June that his career came to a bloody end at Waterloo, with defeat at the hands of an allied army led by Britain’s Wellington and Prussia’s Blucher. But while the Emperor himself is dead and gone, the Napoleon Myth marches on, and is celebrated in some unlikely quarters.

This year marks the 200th anniversary of Napoleon Bonaparte’s death in exile on the island of St Helena. And it was 206 years ago last June that his career came to a bloody end at Waterloo, with defeat at the hands of an allied army led by Britain’s Wellington and Prussia’s Blucher. But while the Emperor himself is dead and gone, the Napoleon Myth marches on, and is celebrated in some unlikely quarters.

Sughra Raza. HAPPY BIRTHDAY JIM CULLENY!

Sughra Raza. HAPPY BIRTHDAY JIM CULLENY! A few years back,

A few years back,

In my Kolkata neighborhood there was one kind of collective action that was unusually successful–this related to religious festivals. Every autumn there was a tremendous collective mobilization of neighborhood resources and youthful energy in organizing the local pujas for one deity or another, and on these occasions almost the whole community participated with devout dedication and considerable ingenuity (including openly pilfering from the public electricity grid for the holy cause—this art locally known as ‘hooking’).

In my Kolkata neighborhood there was one kind of collective action that was unusually successful–this related to religious festivals. Every autumn there was a tremendous collective mobilization of neighborhood resources and youthful energy in organizing the local pujas for one deity or another, and on these occasions almost the whole community participated with devout dedication and considerable ingenuity (including openly pilfering from the public electricity grid for the holy cause—this art locally known as ‘hooking’). There are momentary flashes in the aesthetic life of an individual which can’t be explained away by the exigencies of personal taste or the broader parameters of gender-biased inclinations. These random epiphanies may or may not have their roots in a psychologically identifiable pantheon of ‘likes’, but when they occur, they yank us from our routine expectations of a work and catapult us into a recessive-compulsive emotional terrain resembling infatuation—with a breathlessness induced by the sudden recognition of something strikingly familiar and yet completely unrelated to us.

There are momentary flashes in the aesthetic life of an individual which can’t be explained away by the exigencies of personal taste or the broader parameters of gender-biased inclinations. These random epiphanies may or may not have their roots in a psychologically identifiable pantheon of ‘likes’, but when they occur, they yank us from our routine expectations of a work and catapult us into a recessive-compulsive emotional terrain resembling infatuation—with a breathlessness induced by the sudden recognition of something strikingly familiar and yet completely unrelated to us. Not long ago, watching an emotional scene between two male Korean detectives in Beyond Evil, I was suddenly transported to Jean Renoir’s anti-war masterpiece

Not long ago, watching an emotional scene between two male Korean detectives in Beyond Evil, I was suddenly transported to Jean Renoir’s anti-war masterpiece

Luxuriating in human ignorance was once a classy fad. Overeducated literary types would read Schopenhauer and Kierkegaard and Dostoevsky and Nietzsche, and soak themselves in the quite intelligent conclusion that ultimate reality cannot be known by Terran primates, no matter how many words they use. They would dwell on the suspicion that anything these primates conceive will be skewed by social, sexual, economic, and religious preconceptions and biases; that the very idea that there is an ultimate reality, with a definable character, may very well be a superstition forced upon us by so humble a force as grammar; that in an absurd life bounded on all sides by illusion, the very best a Terran primate might do is to at least be honest with itself, and compassionate toward its colleagues, so that we might all get through this thing together.

Luxuriating in human ignorance was once a classy fad. Overeducated literary types would read Schopenhauer and Kierkegaard and Dostoevsky and Nietzsche, and soak themselves in the quite intelligent conclusion that ultimate reality cannot be known by Terran primates, no matter how many words they use. They would dwell on the suspicion that anything these primates conceive will be skewed by social, sexual, economic, and religious preconceptions and biases; that the very idea that there is an ultimate reality, with a definable character, may very well be a superstition forced upon us by so humble a force as grammar; that in an absurd life bounded on all sides by illusion, the very best a Terran primate might do is to at least be honest with itself, and compassionate toward its colleagues, so that we might all get through this thing together. When King Midas asked Silenus what the best thing for man is, Silenus replied, “It is better not to have been born at all. The next best thing for man would be to die quickly.”

When King Midas asked Silenus what the best thing for man is, Silenus replied, “It is better not to have been born at all. The next best thing for man would be to die quickly.”

Sughra Raza. Untitled. April 2021

Sughra Raza. Untitled. April 2021