by A. Minh Nguyen

On the morning of July 29, 2021, I woke up to the news that Minnesota native Sunisa Lee, also known as Suni, had become the 2020 Olympic individual all-around champion in women’s gymnastics, the first Asian of any nationality to achieve this distinction. How much does Suni Lee’s Olympic gold medal victory mean for an Asian American father such as myself? A lot — although before the Summer Olympics in Tokyo I had no idea who she was. I didn’t even know who Simone Biles was. Two days before, Lee was a member of the squad that won silver in women’s team all-around, and three days after her gold medal performance, she won bronze in uneven bars.

Like other Americans, I was overjoyed by Lee’s multi-medal win at the Tokyo Olympics, especially because she did it in the face of adversity. She overcame so many obstacles: her father’s fall off a ladder in 2019 that paralyzed him from the waist down, the deaths of her aunt and uncle from COVID-19 in 2020, and her own leg and foot injury that sidelined her for two months last year.

The fact that Lee was the first Hmong American Olympian, let alone the first Hmong American Olympic multi-medalist, was extra special for me. Like her parents, Houa John Lee and Yeev Thoj, refugees who immigrated to the United States from Laos via Thailand as children, I was a minor — an unaccompanied minor — from communist Vietnam who spent 17 months in two refugee camps in Indonesia. So was my wife Nhi even though she and her family reached the U.S. by way of a refugee camp in the Philippines. As a fellow child refugee from Southeast Asia, I could imagine Lee’s parents’ struggles. I could imagine their dreams.

Asian Americans are lauded as the model minority. We are praised as exemplars of unproblematic assimilation, upward mobility, and traditional family values. Our aptitudes and attitudes inspire positive thoughts and feelings. Yet this comforting cliché masks a more complicated reality. Wealth, income, education, occupation, and other measures of socioeconomic status vary drastically among Asian Americans both within and across communities of different ethnic backgrounds and national origins. Those variations depend on a number of factors such as geographical location within the U.S. and histories of migration. However you slice it, there is no way that Southeast Asian Americans — in particular Hmong Americans, nearly 60 percent of whom are low-income and more than 25 percent of whom live below the poverty line[1] — sit comfortably within the gauzy dream of a fictitious model minority. Read more »

The day I began writing this essay, Portland Oregon braced for yet another round of uncharacteristic heat. Over several months of preparation, as I had been reading and pondering Kim Stanley Robinson’s big, detailed, hyper-realistic science-fiction book The Ministry for the Future, our normally cool northwest town had found itself repeatedly facing drought and high temperatures. Now we were about to be trapped under a “heat dome” of 115 degrees Fahrenheit (46° C) – Las Vegas temperatures, Abu-Dhabi temperatures – for days on end.

The day I began writing this essay, Portland Oregon braced for yet another round of uncharacteristic heat. Over several months of preparation, as I had been reading and pondering Kim Stanley Robinson’s big, detailed, hyper-realistic science-fiction book The Ministry for the Future, our normally cool northwest town had found itself repeatedly facing drought and high temperatures. Now we were about to be trapped under a “heat dome” of 115 degrees Fahrenheit (46° C) – Las Vegas temperatures, Abu-Dhabi temperatures – for days on end.

Theories that specify which properties are essential for an object to be a work of art are perilous. The nature of art is a moving target and its social function changes over time. But if we’re trying to capture what art has become over the past 150 years within the art institutions of Europe and the United States, we must make room for the central role of creativity and originality. Objects worthy of the honorific “art” are distinct from objects unsuccessfully aspiring to be art by the degree of creativity or originality on display. (I am understanding “art” as a normative concept here.)

Theories that specify which properties are essential for an object to be a work of art are perilous. The nature of art is a moving target and its social function changes over time. But if we’re trying to capture what art has become over the past 150 years within the art institutions of Europe and the United States, we must make room for the central role of creativity and originality. Objects worthy of the honorific “art” are distinct from objects unsuccessfully aspiring to be art by the degree of creativity or originality on display. (I am understanding “art” as a normative concept here.)

Even though I arrived at Economics with the aim of interpreting history, it soon gave me a more general perspective. First, it showed me the value of precision and empirical testing in thinking about socially important issues. This immediately appealed to me, as two of the first courses I liked in college were on Deductive and Inductive Logic. More importantly, Economics gave me a deeper understanding of the incentive mechanisms that sustain social institutions. It made me think why some of the glib solutions suggested by my leftist friends were difficult to sustain in the real world, unless based on motivations/norms and constraints of people in that world. Why are cooperatives and nationalized industries, suggested as substitutes for private enterprise, often (not always) dysfunctional? Economics asks the question: if there is a social problem, why does it not get resolved by the people on their own, and if your answer is that it is the ‘system’ that is to blame—which was the main message of many leftist stories I read and plays/movies I watched—Economics teaches us to go beyond and look into the underlying mechanism through which that ‘system’ is perpetuated or occasionally broken.

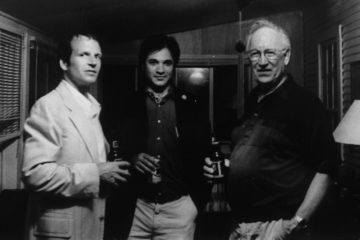

Even though I arrived at Economics with the aim of interpreting history, it soon gave me a more general perspective. First, it showed me the value of precision and empirical testing in thinking about socially important issues. This immediately appealed to me, as two of the first courses I liked in college were on Deductive and Inductive Logic. More importantly, Economics gave me a deeper understanding of the incentive mechanisms that sustain social institutions. It made me think why some of the glib solutions suggested by my leftist friends were difficult to sustain in the real world, unless based on motivations/norms and constraints of people in that world. Why are cooperatives and nationalized industries, suggested as substitutes for private enterprise, often (not always) dysfunctional? Economics asks the question: if there is a social problem, why does it not get resolved by the people on their own, and if your answer is that it is the ‘system’ that is to blame—which was the main message of many leftist stories I read and plays/movies I watched—Economics teaches us to go beyond and look into the underlying mechanism through which that ‘system’ is perpetuated or occasionally broken. Recently I came upon this photo of my friend Eric, me, and his father, tucked into a book that I was trying to place in the correct place on my shelves as a part of a recent book-organizing effort and it made me think about one of the scarier events in my life. It was 2004. It was also only a couple of years after 9/11 and by then the Patriot Act was in full effect and I personally knew completely innocent people who had been caught up in the “bad Muslim” dragnet and had been detained, deported from America, etc. It was in this atmosphere that I was invited to attend my good friend Eric’s wedding on a lake in Michigan. I found the cheapest ticket possible which would involve a stopover in Pittsburgh on the way to Detroit from NYC and a stop in Philadelphia on the way back. I also reserved a rental car at the Detroit airport to get to the rural lake where the wedding was going to be.

Recently I came upon this photo of my friend Eric, me, and his father, tucked into a book that I was trying to place in the correct place on my shelves as a part of a recent book-organizing effort and it made me think about one of the scarier events in my life. It was 2004. It was also only a couple of years after 9/11 and by then the Patriot Act was in full effect and I personally knew completely innocent people who had been caught up in the “bad Muslim” dragnet and had been detained, deported from America, etc. It was in this atmosphere that I was invited to attend my good friend Eric’s wedding on a lake in Michigan. I found the cheapest ticket possible which would involve a stopover in Pittsburgh on the way to Detroit from NYC and a stop in Philadelphia on the way back. I also reserved a rental car at the Detroit airport to get to the rural lake where the wedding was going to be. Philosophers are prone to define

Philosophers are prone to define  This week I had planned to present the 3 Quarks Daily readership with a fluffy little piece about my memories of a grade school foreign language teacher. It was poignant, it was heartfelt, it was funny (if I do say so myself). Above all, it was intended as a brief respite from the nonstop parade of horrors scrolling past our screens every day—a parade in which my own recent writings have occupied a lavishly decorated float. We all deserve a break, I thought. It would be nice to look at some baton twirlers for a minute, listen to an oompa band.

This week I had planned to present the 3 Quarks Daily readership with a fluffy little piece about my memories of a grade school foreign language teacher. It was poignant, it was heartfelt, it was funny (if I do say so myself). Above all, it was intended as a brief respite from the nonstop parade of horrors scrolling past our screens every day—a parade in which my own recent writings have occupied a lavishly decorated float. We all deserve a break, I thought. It would be nice to look at some baton twirlers for a minute, listen to an oompa band.

Sughra Raza. Karachi Afternoon Sun, 2010.

Sughra Raza. Karachi Afternoon Sun, 2010.