by Charlie Huenemann

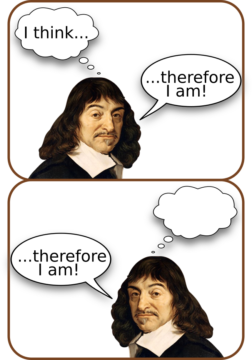

We primates of the homo sapiens variety are very clever when it comes to making maps and plotting courses over dodgy terrain, so it comes as no surprise that we are prone to think of possible actions over time as akin to different paths across a landscape. A choice that comes to me in time can be seen easily as the choice between one path or another, even when geography really has nothing to do with it. My decision to emit one string of words rather than another, or to slip into one attitude or another, or to roll my eyes or stare stolidly ahead, can all be described as taking the path on the right instead the path on the left. And because we primates of the homo sapiens variety are notably bad at forecasting the consequences of our decisions, the decision to choose one path and lose access to the other, forever, can be momentous and frightening. It’s often better to stay in bed.

We primates of the homo sapiens variety are very clever when it comes to making maps and plotting courses over dodgy terrain, so it comes as no surprise that we are prone to think of possible actions over time as akin to different paths across a landscape. A choice that comes to me in time can be seen easily as the choice between one path or another, even when geography really has nothing to do with it. My decision to emit one string of words rather than another, or to slip into one attitude or another, or to roll my eyes or stare stolidly ahead, can all be described as taking the path on the right instead the path on the left. And because we primates of the homo sapiens variety are notably bad at forecasting the consequences of our decisions, the decision to choose one path and lose access to the other, forever, can be momentous and frightening. It’s often better to stay in bed.

Indeed, because every decision cuts the future in half, the space of possibilities is carved rapidly into strange and unexpected shapes, causing us to gaze at one another imploringly and ask, “How ever did such a state of things come to pass?” And the answer, you see, is that we and our compatriots made one decision, and then another, and then another, and before long we found ourselves in this fresh hot mess. And we truly need not ascribe “evil” intentions to anyone in the decision chain, as much as we would like to, since our own futuromyopia supplies all the explanation that is needed. We stumble along in the forever blurry present, bitching as we go, like an ill-tempered Mr. Magoo. Read more »

At ISI one day the American economist Daniel Thorner walked into my office and engaged me in a lively conversation, with his dancing eyebrows and unbounded enthusiasm. I had, of course, read his many substantive papers in EW on Indian agriculture and economic history. I also knew how in the early 1950’s, in the McCarthy era, he had lost his job at University of Pennsylvania for refusing to give information on his leftist friends, and then went on to live in India, with his wife Alice (a fellow India-scholar) for 10 years, before taking up a position in Paris. Now when he came to see me he had just read my EPW paper showing on the basis of NSS data that poverty had increased over the 1960’s in rural India. He asked me not to put so much trust on NSS data (he jokingly said that increasing poverty estimates by NSS data might be a reflection more of the increasing sense of misery on the part of the underpaid NSS workers), and to accompany him in his next trip to Punjab villages where he promised to introduce me to beer-drinking tractor-driving women farmers, the harbingers of the future of agricultural capitalism in India. Much of what he said was, of course, tongue-in-cheek, and we became good friends. But this friendship was to be a ‘brief candle’, as cancer soon cut his life short.

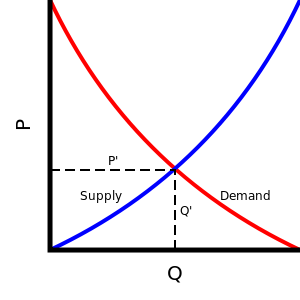

At ISI one day the American economist Daniel Thorner walked into my office and engaged me in a lively conversation, with his dancing eyebrows and unbounded enthusiasm. I had, of course, read his many substantive papers in EW on Indian agriculture and economic history. I also knew how in the early 1950’s, in the McCarthy era, he had lost his job at University of Pennsylvania for refusing to give information on his leftist friends, and then went on to live in India, with his wife Alice (a fellow India-scholar) for 10 years, before taking up a position in Paris. Now when he came to see me he had just read my EPW paper showing on the basis of NSS data that poverty had increased over the 1960’s in rural India. He asked me not to put so much trust on NSS data (he jokingly said that increasing poverty estimates by NSS data might be a reflection more of the increasing sense of misery on the part of the underpaid NSS workers), and to accompany him in his next trip to Punjab villages where he promised to introduce me to beer-drinking tractor-driving women farmers, the harbingers of the future of agricultural capitalism in India. Much of what he said was, of course, tongue-in-cheek, and we became good friends. But this friendship was to be a ‘brief candle’, as cancer soon cut his life short. Every Econ 101 student learns the basic model of demand and supply. It’s pretty straight forward. Picture a graph with the price of a product or service on the vertical axis and the quantity supplied and demanded on the horizontal axis. There are two curves drawn on this graph: the demand curve and the supply curve. The demand curve is downward sloping because as prices decrease, consumers are willing to buy more. The supply curve is upward sloping because producers are willing to supply more when they are paid more. The “competitive equilibrium price” of the product or service is where supply equals demand: two curves intersect. When prices are higher than the equilibrium price, supply is greater than demand: there is “excess supply”. This makes sense: at higher prices, suppliers are going to be happy to sell more, but consumers aren’t willing to buy as much.

Every Econ 101 student learns the basic model of demand and supply. It’s pretty straight forward. Picture a graph with the price of a product or service on the vertical axis and the quantity supplied and demanded on the horizontal axis. There are two curves drawn on this graph: the demand curve and the supply curve. The demand curve is downward sloping because as prices decrease, consumers are willing to buy more. The supply curve is upward sloping because producers are willing to supply more when they are paid more. The “competitive equilibrium price” of the product or service is where supply equals demand: two curves intersect. When prices are higher than the equilibrium price, supply is greater than demand: there is “excess supply”. This makes sense: at higher prices, suppliers are going to be happy to sell more, but consumers aren’t willing to buy as much.

Sughra Raza. First Snow 2022.

Sughra Raza. First Snow 2022. On the anniversary of the attempt by Donald Trump and some of his supporters to subvert the 2020 US presidential election, Joe Biden denounced those who “place a dagger at the throat of democracy.” To which one can only say: About bloody time! The threat posed by Trump and the Republican party to America’s democratic institutions–highly imperfect though they are–is so obvious that anyone who has a bully pulpit should be pounding out a warning at every opportunity.

On the anniversary of the attempt by Donald Trump and some of his supporters to subvert the 2020 US presidential election, Joe Biden denounced those who “place a dagger at the throat of democracy.” To which one can only say: About bloody time! The threat posed by Trump and the Republican party to America’s democratic institutions–highly imperfect though they are–is so obvious that anyone who has a bully pulpit should be pounding out a warning at every opportunity. A large number of jobs exist not because they create economic value but because they make business sense given the institutions we have – customer expectations, bureaucratic regulations, and so on. They do not solve a real problem but a fake problem created by inefficient institutions. They therefore do not make our society better off but rather they represent a great cost to society – of many people’s time being expended on something fundamentally pointless instead of something worthwhile. One way of spotting such anti-jobs is to compare staffing in the same industry across different countries. US supermarkets employ people just to greet customers and bag groceries, for example, which would seem a ridiculous waste of time in most of the world. In Japan one can find people standing in front of road construction waving a flag (they are replaced with mechanical manikins on nights and weekends).

A large number of jobs exist not because they create economic value but because they make business sense given the institutions we have – customer expectations, bureaucratic regulations, and so on. They do not solve a real problem but a fake problem created by inefficient institutions. They therefore do not make our society better off but rather they represent a great cost to society – of many people’s time being expended on something fundamentally pointless instead of something worthwhile. One way of spotting such anti-jobs is to compare staffing in the same industry across different countries. US supermarkets employ people just to greet customers and bag groceries, for example, which would seem a ridiculous waste of time in most of the world. In Japan one can find people standing in front of road construction waving a flag (they are replaced with mechanical manikins on nights and weekends).