by Joseph Shieber

In a recent short post on “ChatGPT and My Career Trajectory,” the prominent blogger, public intellectual, and GMU economist Tyler Cowen sees AI as posing a threat to the future of public intellectuals. (For what it’s worth, Michael Orthofer, the writer of the excellent Complete Review book review website, seems to agree.)

Cowen writes:

For any given output, I suspect fewer people will read my work. You don’t have to think the GPTs can copy me, but at the very least lots of potential readers will be playing around with GPT in lieu of doing other things, including reading me. After all, I already would prefer to “read GPT” than to read most of you. …

Well-known, established writers will be able to “ride it out” for long enough, if they so choose. There are enough other older people who still care what they think, as named individuals, and that will not change until an entire generational turnover has taken place. …

Today, those who learn how to use GPT and related products will be significantly more productive. They will lead integrated small teams to produce the next influential “big thing” in learning and also in media.

I share Cowen’s sense that intellectuals (public or not) shouldn’t ignore the rapidly ever-more-sophisticated forms of AI, including ChatGPT. However, I’m not sure that Cowen is right to suggest that AI output will supplant human output – particularly if he’s making the stronger, normative claim that such a development is actually commendable.

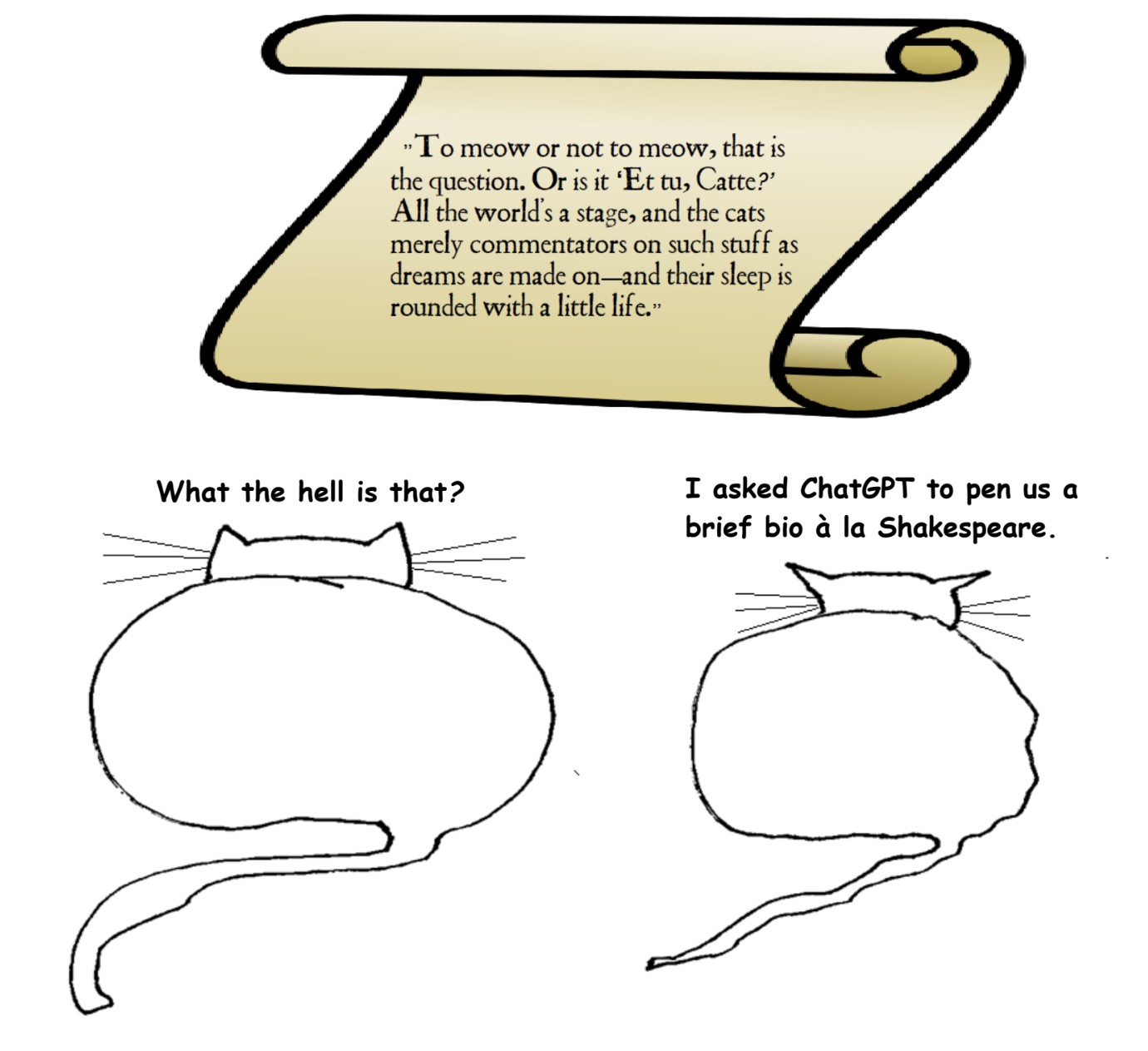

There seem to be three reasons to interact with ChatGPT, all of which can be teased out from Cowen’s comments. First, you could treat ChatGPT as a content creator. Second, you could treat ChatGPT as a facilitator for your own content creation. Finally, you could treat ChatGPT as an interlocutor. (Of course, these ways of interacting with ChatGPT are not mutually exclusive.)

Let’s deal with these ways of interacting with ChatGPT in order. Read more »

Flor Garduno. Basket of Light, Sumpango, Guatemala. 1989.

Flor Garduno. Basket of Light, Sumpango, Guatemala. 1989.

In 1965, John McPhee wrote an article for The New Yorker titled “

In 1965, John McPhee wrote an article for The New Yorker titled “

Watching the Oathkeepers cry during the federal court trials under the charge of sedition, I considered the fate of seditious Loyalists during the Revolutionary War whom they most closely resemble in the topsy-turvy world of contemporary politics. The Revolutionary War was a civil war, combatants were united with a common language and heritage that made each side virtually indistinguishable. Even before hostilities were underway, spies were everywhere, and treason inevitable. Defining treason is the first step in delineating one country from another, and indeed, the five-member “Committee on Spies’ ‘ was organized before the Declaration of Independence was written.

Watching the Oathkeepers cry during the federal court trials under the charge of sedition, I considered the fate of seditious Loyalists during the Revolutionary War whom they most closely resemble in the topsy-turvy world of contemporary politics. The Revolutionary War was a civil war, combatants were united with a common language and heritage that made each side virtually indistinguishable. Even before hostilities were underway, spies were everywhere, and treason inevitable. Defining treason is the first step in delineating one country from another, and indeed, the five-member “Committee on Spies’ ‘ was organized before the Declaration of Independence was written.