Sarah Beckwith at nonsite:

“To read a text isn’t to discover new facts about it,” says Moi, “it is to figure out what it has to say to us.”6 Understanding, meaning as use, responsiveness, responsibility, acknowledgement, the precision and inheritance of language: these are Toril Moi’s concerns in her refreshing, vitally important, generative book, a book that has the capacity to liberate us from language as a prison-house, and challenges and invites us into our own responsibility in words, as writers, readers, theorists, and critics. Moi wants us to wake up to the complexities of our inheritance of and use of language as if to invite us to exercise some stiffened and inflexible muscles to find greater, more various strengths and capacities. This is what makes this book such an exhilarating challenge and invitation at a time when literary studies seems to veer between the false allure of scientism (neurohumanities, “digital” humanities) and a fierce, entrenched moralism (which I take to be a stance which by-passes one’s own responses) and the professionalized credentializing, which sometimes appears to measure rather than judge academic work, all of which might break a graduate student’s spirit before she gets the chance to find her intellectual companions, and stand in the way of why she might ever have loved reading, thinking, and writing in the first place.

“To read a text isn’t to discover new facts about it,” says Moi, “it is to figure out what it has to say to us.”6 Understanding, meaning as use, responsiveness, responsibility, acknowledgement, the precision and inheritance of language: these are Toril Moi’s concerns in her refreshing, vitally important, generative book, a book that has the capacity to liberate us from language as a prison-house, and challenges and invites us into our own responsibility in words, as writers, readers, theorists, and critics. Moi wants us to wake up to the complexities of our inheritance of and use of language as if to invite us to exercise some stiffened and inflexible muscles to find greater, more various strengths and capacities. This is what makes this book such an exhilarating challenge and invitation at a time when literary studies seems to veer between the false allure of scientism (neurohumanities, “digital” humanities) and a fierce, entrenched moralism (which I take to be a stance which by-passes one’s own responses) and the professionalized credentializing, which sometimes appears to measure rather than judge academic work, all of which might break a graduate student’s spirit before she gets the chance to find her intellectual companions, and stand in the way of why she might ever have loved reading, thinking, and writing in the first place.

more here.

The truth, as strongly suggested in Eugene Onegin, is that Pushkin’s attitudes towards the country were as conflicted as the twin self the novel in verse projects. When he stayed at Mikhailovskoye after graduating from his elite Petersburg lycée he was both delighted and impatient. ‘I remember how happy I was with village life, Russian baths, strawberries and so on,’ he wrote. ‘But all this did not please me for long.’ In the country he was constantly riding out to find companionship, love and sex among his gentry neighbours – failing that, to have sex with one of the family serfs – but still had time enough for composition. In one three-month autumn stay in Boldino, where he was less desperate for company – just engaged, but without his future wife, Natalya Goncharova – he wrote thirty poems, all five Tales of Belkin and the satirical History of the Village of Goryukhino. He also wrote the ending of Eugene Onegin and four short plays, including Mozart and Salieri, the work by which he is – invisibly – best known to modern popular culture outside Russia, via the Peter Shaffer play it inspired, Amadeus, rendered onto the big screen by Miloš Forman.

The truth, as strongly suggested in Eugene Onegin, is that Pushkin’s attitudes towards the country were as conflicted as the twin self the novel in verse projects. When he stayed at Mikhailovskoye after graduating from his elite Petersburg lycée he was both delighted and impatient. ‘I remember how happy I was with village life, Russian baths, strawberries and so on,’ he wrote. ‘But all this did not please me for long.’ In the country he was constantly riding out to find companionship, love and sex among his gentry neighbours – failing that, to have sex with one of the family serfs – but still had time enough for composition. In one three-month autumn stay in Boldino, where he was less desperate for company – just engaged, but without his future wife, Natalya Goncharova – he wrote thirty poems, all five Tales of Belkin and the satirical History of the Village of Goryukhino. He also wrote the ending of Eugene Onegin and four short plays, including Mozart and Salieri, the work by which he is – invisibly – best known to modern popular culture outside Russia, via the Peter Shaffer play it inspired, Amadeus, rendered onto the big screen by Miloš Forman. No novel of the past century

No novel of the past century The average person eats at least 50,000 particles of microplastic a year and breathes in a similar quantity, according to the first study to estimate human ingestion of plastic pollution. The true number is likely to be many times higher, as only a small number of foods and drinks have been analysed for plastic contamination. The scientists reported that drinking a lot of bottled water drastically increased the particles consumed. The health impacts of ingesting microplastic are unknown, but they could release toxic substances. Some pieces are small enough to penetrate human tissues, where they could trigger immune reactions.

The average person eats at least 50,000 particles of microplastic a year and breathes in a similar quantity, according to the first study to estimate human ingestion of plastic pollution. The true number is likely to be many times higher, as only a small number of foods and drinks have been analysed for plastic contamination. The scientists reported that drinking a lot of bottled water drastically increased the particles consumed. The health impacts of ingesting microplastic are unknown, but they could release toxic substances. Some pieces are small enough to penetrate human tissues, where they could trigger immune reactions. The big question that I keep asking myself at the moment is whether it’s possible that predictive processing, the vision of the predictive mind I’ve been working on lately, is as good as it seems to be. It keeps me awake a little bit at night wondering whether anything could touch so many bases as this story seems to. It looks to me as if it provides a way of moving towards a third generation of artificial intelligence. I’ll come back to that in a minute. It also looks to me as if it shows how the stuff that I’ve been interested in for so long, in terms of the extended mind and embodied cognition, can be both true and scientifically tractable, and how we can get something like a quantifiable grip on how neural processing weaves together with bodily processing weaves together with actions out there in the world. It also looks as if this might give us a grip on the nature of conscious experience. And if any theory were able to do all of those things, it would certainly be worth taking seriously. I lie awake wondering whether any theory could be so good as to be doing all these things at once, but that’s what we’ll be talking about.

The big question that I keep asking myself at the moment is whether it’s possible that predictive processing, the vision of the predictive mind I’ve been working on lately, is as good as it seems to be. It keeps me awake a little bit at night wondering whether anything could touch so many bases as this story seems to. It looks to me as if it provides a way of moving towards a third generation of artificial intelligence. I’ll come back to that in a minute. It also looks to me as if it shows how the stuff that I’ve been interested in for so long, in terms of the extended mind and embodied cognition, can be both true and scientifically tractable, and how we can get something like a quantifiable grip on how neural processing weaves together with bodily processing weaves together with actions out there in the world. It also looks as if this might give us a grip on the nature of conscious experience. And if any theory were able to do all of those things, it would certainly be worth taking seriously. I lie awake wondering whether any theory could be so good as to be doing all these things at once, but that’s what we’ll be talking about. The fire chaser beetle, as its name implies, spends its life trying to find a forest fire.

The fire chaser beetle, as its name implies, spends its life trying to find a forest fire. The IPBES Global Assessment estimated that 1 million animal and plant species are threatened with extinction. It also documents how

The IPBES Global Assessment estimated that 1 million animal and plant species are threatened with extinction. It also documents how  Advocates of the Green New Deal say there is great urgency in dealing with the climate crisis and highlight the scale and scope of what is required to combat it. They are right. They use the term “New Deal” to evoke the massive response by Franklin Delano Roosevelt and the United States government to the Great Depression. An even better analogy would be the country’s mobilization to fight World War II.

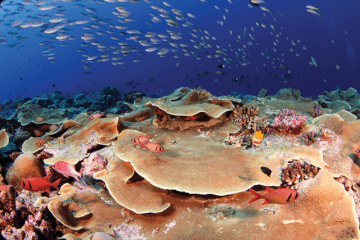

Advocates of the Green New Deal say there is great urgency in dealing with the climate crisis and highlight the scale and scope of what is required to combat it. They are right. They use the term “New Deal” to evoke the massive response by Franklin Delano Roosevelt and the United States government to the Great Depression. An even better analogy would be the country’s mobilization to fight World War II. Today, news of damaged or devastated coral reefs has become commonplace. Reefs face many threats, including bleaching, disease, overfishing, pollution and even invasive species. While the fates of the reefs may seem almost universally bleak, some scientists think the future of these vital marine ecosystems could be more complicated—and perhaps even hopeful. Ecologist

Today, news of damaged or devastated coral reefs has become commonplace. Reefs face many threats, including bleaching, disease, overfishing, pollution and even invasive species. While the fates of the reefs may seem almost universally bleak, some scientists think the future of these vital marine ecosystems could be more complicated—and perhaps even hopeful. Ecologist  One Saturday night a few months ago, a friend of mine who works in the tech industry announced the good news that she and her husband were expecting a baby. This September, they will engage in that quintessential parenting ritual: a mad dash to the hospital and the return home with their newborn. Their birth experience, however, will have a modern twist. My friend is not having the baby herself. Their new arrival will come courtesy of a female stranger whom they screened, paid and entrusted to incubate their embryo. Only after their surrogate goes into labour will they make their way to the hospital, flying from the Bay Area to southern California, where their surrogate lives and will deliver their child.

One Saturday night a few months ago, a friend of mine who works in the tech industry announced the good news that she and her husband were expecting a baby. This September, they will engage in that quintessential parenting ritual: a mad dash to the hospital and the return home with their newborn. Their birth experience, however, will have a modern twist. My friend is not having the baby herself. Their new arrival will come courtesy of a female stranger whom they screened, paid and entrusted to incubate their embryo. Only after their surrogate goes into labour will they make their way to the hospital, flying from the Bay Area to southern California, where their surrogate lives and will deliver their child. David Papineau in Aeon:

David Papineau in Aeon: Bhakti Shringarpure in Africa is Not a Country:

Bhakti Shringarpure in Africa is Not a Country:

Henry Farrell interviews Sheri Berman over at the Washington Post:

Henry Farrell interviews Sheri Berman over at the Washington Post:

What a difference a decade makes. In 1940 George Orwell published his eighth book, the essay collection Inside the Whale, but when the Nazis in the same year drew up a list of Britons to be arrested after the planned invasion, his name wasn’t included. It was, observes Dorian Lynskey in his superb new book, ‘a kind of snub’. By the time Orwell died in January 1950, however, he was being acclaimed around the Western world as one of the great defenders of democracy and liberty, and had just been adjudged, for the first time, worthy of an entry in Who’s Who.

What a difference a decade makes. In 1940 George Orwell published his eighth book, the essay collection Inside the Whale, but when the Nazis in the same year drew up a list of Britons to be arrested after the planned invasion, his name wasn’t included. It was, observes Dorian Lynskey in his superb new book, ‘a kind of snub’. By the time Orwell died in January 1950, however, he was being acclaimed around the Western world as one of the great defenders of democracy and liberty, and had just been adjudged, for the first time, worthy of an entry in Who’s Who.