Issues

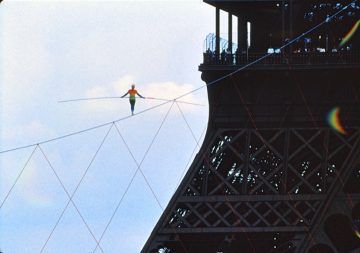

the man who climbed the Brooklyn Bridge

who walked the highest cables

and swung hand-over-hand from one side

to the other who eluded ten cops with harnesses

and ropes a helicopter a boat below

with emergency crews and a backboard

who asked for a cigarette and a beer who swung

upside down with his knees hooked

around a cable and took a cigarette

from one cop’s hand and smoked it laughing

and then flipped over and slid down fireman-style

one cable and upside down again around another

and skirted between the outstretched hands of two cops

and again and then again

who after two hours of this

with a crowd gathered on the pedestrian walkway

of the Manhattan Bridge and traffic stopped

in both directions on the Brooklyn Bridge

with all of us looking up from the Fulton Ferry landing

where Whitman wrote about us the generations hence

but probably couldn’t have imagined

the cell phones and laptops all the exposed skin

and his words themselves cut out of the metal railing

between the defunct ferry landing and East River

who finally gave up gave over

to the embrace of one big-shouldered cop

and hugged him hard for a long time

as we started our applause from down below

was not an acrobat or a bridge worker

or a thrill-seeker

as many of us with our feet on the ground believed

including one gnarled hardhat who said

if he ain’t one of ours let’s sign him up

but a “simple welder” the paper the next day said

who according to his mother did very well

at gymnastics in high school

whose bloody hands stained the cop’s shirt

said when asked why he did what he did

I have issues

while we with issues but perhaps not issues enough

to become suddenly the best show in town

however briefly clapped and clapped

as if we wanted our hands bloodied like his

as the helicopter whisked itself away

and the backboard went back into the ambulance

and the boat slid under the bridge and out of sight

we clapped and clapped and then stopped clapping

and returned to our morning

and our ever so many mornings hence.

by Denver Butson

from illegible address

Luquer Street Press, 2004.

The Spercheios river—which, legend tells us, was dear to the warrior Achilles—marks the southern boundary of the great Thessalian plain in central Greece. I arrived there in late October, but it still felt like summer, and few people were around. Away on the left, the foothills of Mount Oiti were hazed with heat. On my right, at some distance from the road, screened by cotton fields and intermittent olive groves, flowed the Spercheios. At the village of Paliourio, road and river converged, and leaving my car, I wandered down a track that led to a shattered bridge shored with makeshift planking. The river itself was sparkling, picturesquely overhung with oak and wild olive, but on closer inspection I saw machinery and discarded appliances rusting in its shallows.

The Spercheios river—which, legend tells us, was dear to the warrior Achilles—marks the southern boundary of the great Thessalian plain in central Greece. I arrived there in late October, but it still felt like summer, and few people were around. Away on the left, the foothills of Mount Oiti were hazed with heat. On my right, at some distance from the road, screened by cotton fields and intermittent olive groves, flowed the Spercheios. At the village of Paliourio, road and river converged, and leaving my car, I wandered down a track that led to a shattered bridge shored with makeshift planking. The river itself was sparkling, picturesquely overhung with oak and wild olive, but on closer inspection I saw machinery and discarded appliances rusting in its shallows. In 1996,

In 1996,  The

The Why did he do it, then? For no other reason, I believe, than to dazzle the world with what he could do. Having seen his stark and haunting juggling performance on the street, I sensed intuitively that his motives were not those of other men—not even those of other artists. With an ambition and an arrogance fit to the measure of the sky, and placing on himself the most stringent internal demands, he wanted, simply, to do what he was capable of doing.

Why did he do it, then? For no other reason, I believe, than to dazzle the world with what he could do. Having seen his stark and haunting juggling performance on the street, I sensed intuitively that his motives were not those of other men—not even those of other artists. With an ambition and an arrogance fit to the measure of the sky, and placing on himself the most stringent internal demands, he wanted, simply, to do what he was capable of doing. Like most of their generation, Coleridge and Wordsworth had embraced the French Revolution and its ideals of liberty and equality, then lived through the shattering reversals of massacre and war that ensued. By the mid-1790s, many of the poets’ acquaintances were racked by mental and emotional stress. Some of them fled the country; others opted for internal exile, hidden, they hoped, from the spies and informers patrolling the cities. Nicolson argues convincingly that the fragmentary, fierce and strange poetry Wordsworth produced before Lyrical Ballads was composed on the cusp of madness. It was only by going to ground in England’s West Country that Wordsworth was able to cope. We get a rare glimpse of him at that time in Dorothy Wordsworth’s remark that her brother is ‘dextrous with a spade’. Like Heaney, Nicolson’s young Romantics are energised by ‘touching territory’ – digging in to renew themselves and their writing. The idea, Nicolson suggests, ‘that the contented life was the earth-connected life, even that goodness was embeddedness … had its roots in the 1790s’. As furze bloomed brightly on Longstone Hill, Coleridge and Wordsworth began to write poems that would challenge ‘pre-established codes’, change how people thought and so remake the world.

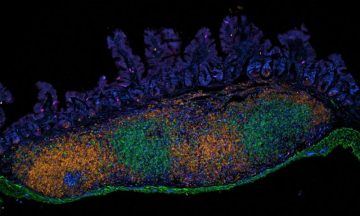

Like most of their generation, Coleridge and Wordsworth had embraced the French Revolution and its ideals of liberty and equality, then lived through the shattering reversals of massacre and war that ensued. By the mid-1790s, many of the poets’ acquaintances were racked by mental and emotional stress. Some of them fled the country; others opted for internal exile, hidden, they hoped, from the spies and informers patrolling the cities. Nicolson argues convincingly that the fragmentary, fierce and strange poetry Wordsworth produced before Lyrical Ballads was composed on the cusp of madness. It was only by going to ground in England’s West Country that Wordsworth was able to cope. We get a rare glimpse of him at that time in Dorothy Wordsworth’s remark that her brother is ‘dextrous with a spade’. Like Heaney, Nicolson’s young Romantics are energised by ‘touching territory’ – digging in to renew themselves and their writing. The idea, Nicolson suggests, ‘that the contented life was the earth-connected life, even that goodness was embeddedness … had its roots in the 1790s’. As furze bloomed brightly on Longstone Hill, Coleridge and Wordsworth began to write poems that would challenge ‘pre-established codes’, change how people thought and so remake the world. Faecal transplants from young to aged mice can stimulate the gut microbiome and revive the gut immune system, a study by immunologists at the Babraham Institute, Cambridge, has shown. The research is published in the journal Nature Communications today. The gut is one of the organs that is most severely affected by ageing and age-dependent changes to the human

Faecal transplants from young to aged mice can stimulate the gut microbiome and revive the gut immune system, a study by immunologists at the Babraham Institute, Cambridge, has shown. The research is published in the journal Nature Communications today. The gut is one of the organs that is most severely affected by ageing and age-dependent changes to the human  ‘Who has the right to speak?’ It is the key question in debates around free speech. Who should be allowed to speak? What should be permitted to be said? And who makes the decision?

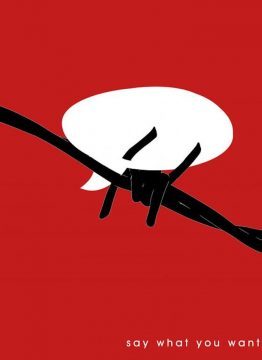

‘Who has the right to speak?’ It is the key question in debates around free speech. Who should be allowed to speak? What should be permitted to be said? And who makes the decision? Three seasons in the NFL? Impressive.

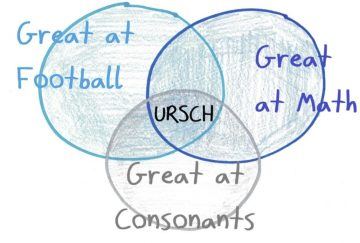

Three seasons in the NFL? Impressive. There is a story that is commonly told in Britain that the colonisation of

There is a story that is commonly told in Britain that the colonisation of  Mosul’s old city lies in ruins. A major section of the third largest city in Iraq has been destroyed by war. Two years after the Iraqi government and the United States-led coalition recaptured it from ISIS, the city is still noticeably scarred. Many residents have fled, or are detained in camps elsewhere in the country. Those who have returned live amid the ruins of their old houses and their old lives. But what is being reconstructed is cultural heritage. UNESCO has worked with the Iraqi government to launch a campaign called ‘Revive the Spirit of Mosul’, focusing on a handful of historic monuments in the city. The United Arab Emirates has pledged $50 million to rebuild the 850-year-old al-Nuri mosque and its minaret, known as al-Hadba (or the hunchback), a symbol of the city.

Mosul’s old city lies in ruins. A major section of the third largest city in Iraq has been destroyed by war. Two years after the Iraqi government and the United States-led coalition recaptured it from ISIS, the city is still noticeably scarred. Many residents have fled, or are detained in camps elsewhere in the country. Those who have returned live amid the ruins of their old houses and their old lives. But what is being reconstructed is cultural heritage. UNESCO has worked with the Iraqi government to launch a campaign called ‘Revive the Spirit of Mosul’, focusing on a handful of historic monuments in the city. The United Arab Emirates has pledged $50 million to rebuild the 850-year-old al-Nuri mosque and its minaret, known as al-Hadba (or the hunchback), a symbol of the city. S

S Could a blood test detect cancer in healthy people? Grail, a Menlo Park, Calif.-based company, has raised $1.6 billion in venture capital to prove the answer is yes. And at the world’s largest meeting of cancer doctors, the company is unveiling data that seem designed to assuage the concerns and fears of its doubters and critics. But outside experts emphasize there is still a long way to go. The data, from a pilot study that Grail is using to develop its diagnostic before running it through the gantlet of two much larger clinical trials, are being presented Saturday in several poster sessions at the

Could a blood test detect cancer in healthy people? Grail, a Menlo Park, Calif.-based company, has raised $1.6 billion in venture capital to prove the answer is yes. And at the world’s largest meeting of cancer doctors, the company is unveiling data that seem designed to assuage the concerns and fears of its doubters and critics. But outside experts emphasize there is still a long way to go. The data, from a pilot study that Grail is using to develop its diagnostic before running it through the gantlet of two much larger clinical trials, are being presented Saturday in several poster sessions at the